Introduction – the context we are working in

Even before the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, schools, and school leaders in particular, were facing significant changes because of OFSTED’s new Inspection framework with its emphasis on breadth and balance in the curriculum. This new framework for school inspection was accompanied by increasingly pressured budgetsa, making it effectively a double squeeze on resources for schools. When one adds in the consequences of adapting to a radically new set of demands on teaching provision around social distanced and online learning in the midst of the pandemic, the effect is to create an environment where school leaders need to raise their professional learning game whilst making every penny count.

It's at times like these that relevant research findings become not merely an optional tool but a vital support mechanism; they help leaders make evidence-informed judgements about where and how they should be investing in CPD and professional learning (CPDL). This article summarises key messages for leaders to incorporate into their thinking, drawn from recent systematic explorations of the dizzying array of evidence into professional development and learning. It offers help with gauging the likely value of both internal and external approaches to CPDL and for working out whether or not what they do is paying dividends for staff and for pupils.

Where does the evidence come from?

The core publication underpinning this piece is Developing Great Leadership of Continuing Professional Development and Learning 2020.1 The report was funded by the charity Right To Succeed, and built on a previous review of research reviews of the evidence about effective CPDL, Developing Great Teaching1 sponsored by the Teacher Development Trust. In both reports, the core goal was to identify systematically what existing research reviews could say about professional development practices and approaches which had strong evidence of improvement of attainment for learners.

A joint team consisting of individuals from multiple education research organisations worked together for both reports to establish a meaningful and coherent picture of the evidence base. The second review updated the first and started the process of mapping the complex and multi layered contributions which leaders make to leading CPDL with positive impacts for both pupils and teachers. The team created systems to evaluate the evidence and then examined the findings to generate conclusions and recommendations.

Headline Findings – What leaders can do to get the most out of the CPD they lead, support or commission?

The first and most important conclusion to draw from the research evidence is that, as Viviane Robinson’s found in her own research into this area2, leaders can and do make an enormous contribution to the professional learning of teachers. This contribution takes a variety of forms depending on specifics, but invariably links both to specific elements of the commissioning of CPDL, and to more generalised issues relating to the work leaders do to shape the direction of the organisations they work in. As an example, leadership can make a significant contribution to the impact of CPDL for teachers that is focused on developing learners’ vocabulary. It does this by both ensuring that the CPDL they bring in has good evidence of impact on the areas of vocabulary needing development, and by signalling (overtly and implicitly) to teachers that participation in CPDL is valued by school leaders and is worth their time and energy to pursue.

More specifically than this however, the research indicates strongly that in order to be effective CPDL needs to be geared towards building a school environment in which it is understood that everyone is an important participant in ongoing learning, and that achieving this rests on an understanding of the complex intellectual as well as emotional needs of all involved. This represents a key area which leaders can adopt as their main specific contribution when planning for and enacting professional learning. Few, if any, people outside of a school’s leadership team are better positioned both to understand and to act on the needs of teachers in that school, or the pupils they work with.

Below these two prominent core findings about the relevance of leadership activities to outcomes of CPDL, there are 6 other key findings from the research. These relate to what leaders can do to ensure that the CPDL which takes place in their school is a) likely to lead to improved outcomes for learners and b) does multiple jobs at once (i.e. provides the best return on investment). These are:

- Positioning/representing CPDL to their colleagues as a part of a process of making sure everyone shares responsibility for excellence in pupil achievement and wellbeing

- Focus on supporting teachers’ long-term professional growth, as well as on developing their specific knowledge and skills

- Explicitly model openness to and engagement with professional learning (including leadership) as part of their other activities

- Design organisational structures & systems for managing the complexity which high-quality CPDL poses for teachers

- Identify and manage the cognitive, practical & emotional demands CPDL content and systems make on teachers

- Recognise and mobilise specialist contributions to CPDL (including expertise about CPDL itself)

In addition to these key contributions the evidence also suggests leaders can make a powerful difference by making sure that the design of CPDL processes is set up to be effective. The key findings here are that leaders should ensure that there is time available for practitioners to plan for incorporating principles from CPDL training into their practice, by protecting teachers’ time and limiting the amount of other burdens they have to grapple with in doing so.

Leaders also need to ensure that CPDL is:

- focussed on specific learning needs;

- builds on a clear understanding of teachers’ feelings about their professional identities, practices and motivation (i.e. that it is apparent to them that it is relevant);

- connects to their approach to learning (e.g. theory-first vs practice-first); and

- takes into account their existing knowledge, skills and beliefs.

Another way in which leaders can make powerful contributions to CPDL is by ensuring that it aligns with and focuses on teachers’ aspirations for their pupils’ achievement and wellbeing (this also relates a broader trend of recognising that the process of learning is powerful but also, often, demanding).

This links to another finding, that leaders should aim to commission and/or contribute to CPDL which emphasises practical theory alongside content and pedagogy. The demanding nature of learning stems from presenting it in multiple forms which enable learners to bring it to bear in different contexts. One way in which those different contexts can be explored is through collaboration and peer support. The evidence indicates that this kind of joint working needs also to be linked with pupil learning, and in particular to exploring new approaches in terms of how pupils respond to them.

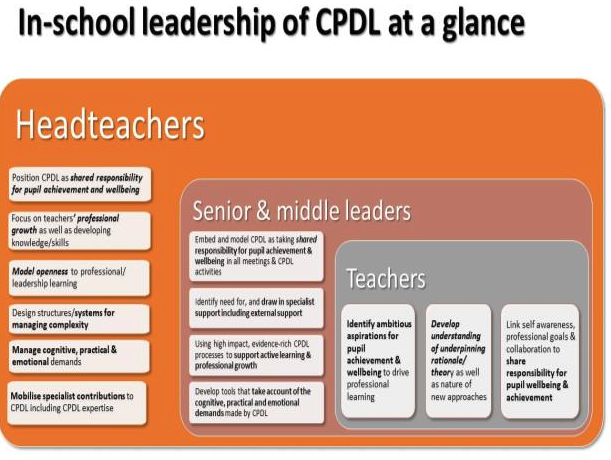

These findings represent a complex set of requirements for leaders to consider but can be thought of both as a series of tests to apply to CPDL packages/programmes when evaluating their suitability for commissioning, and as a framework for thinking about CPDL as a joint enterprise within a school. This last part can be demonstrated by laying the findings out in terms of whom they are particularly relevant for, as seen in Figure 1 below:

What about the curriculum and professional development?

The evidence around curriculum development does not stand alone from the wider evidence about effective leadership of CPDL in general terms. Findings about effective leadership of curriculum frequently link with and sometimes mirror those about leading CPDL. Broadly speaking this evidence suggests that, where leaders are thinking about CPDL on curriculum development, they should focus in particular on:

- Aligning CPDL with the context, values and background of the school as a whole, and by extension the community that it serves to create coherence. Integrating curriculum development and implementation with the wider CPDL offer helps secure depth and increase the coherence of learning experiences for pupils and for staff, especially across transitions.

- Organising curriculum development alongside CPDL explicitly as a means of sharing responsibility for meeting ambitious goals and building ownership of the content. Curriculum design depends on CPDL and is a fantastic vehicle for it so long as strong CPDL protocols are wrapped around curriculum development activities. In particular, care should be taken to debrief the professional learning that flows form not just to review its outcomes for pupils.

An interesting feature of this evidence suggests that effective leadership of curriculum development and CPDL involves recognising the contribution of specialist expertise to CPDL in securing depth of teachers’ knowledge, skills and practice (which in turns contributes to pupils’ own awareness and development). The research identifies several key aspects of this process.

Firstly, leaders should reflect on and discuss their own (and their senior colleagues’) specialist knowledge and the role it played in their own development. This not only makes overt valuable expertise but also makes it easier for colleagues to recognise the value it provides when it comes from other disciplines, such as different subjects or modes of education (e.g. research originating in vocational education being accessed by academic teachers). Leaders can and should also work to understand and develop the specialist knowledge and skills of curriculum developers in CPDL, so that they can make and also take advantage of links between them.

It is worth noting that perhaps the most important contribution leaders can make to CPDL for curriculum development is in the commissioning process, taking care to commission CPDL activities, tools and protocols, with the goal of supporting coherent experiences for pupils. This evidence also suggests coherence in commissioning will be enhanced if leaders analyse and take account of not just the practical demands imposed by new policies and systems, but also the cognitive and emotional demands such policies and approaches are making on colleagues.

These considerations will help teachers navigate the complexity which accompanies innovation rather than leaving their students to cope with any accidental fall out as different teachers assimilate different understandings.

Another useful element of the research evidence is the way it produces a “map” of findings which leaders can use to test the systems, tools and protocols/policies they use to create positive and powerful CPDL environments. They can do this by evaluating specifically and explicitly:

- how far they work to avoid focusing on CPDL which simply flags up bodies of knowledge which have no clear connection to the process of bringing knowledge to life in practical terms within a school context;

- how much they build intellectual coherence in curriculum experiences which stand up across different phases, and;

- how they ensure that those who lead curriculum development understand the evidence about good CPDL, and vice versa

There are some caveats to apply to the above. Although the team was able to find systematic reviews with evidence of pupil impact which overlapped with this area of leadership, there were not enough which addressed the specific topic of curriculum development. As a result, the findings about leadership of curriculum development are extrapolated instead of having direct evidence.

This means that they reflect very closely the findings about wider leadership of CPDL, and may miss some important distinctions when it comes to the practical details of how leaders effectively contribute to curriculum development. While it is not a good idea to treat any research evidence as a “recipe book” for effectiveness without thinking about what differences local context might make, this is particularly important to remember in an area with limited direct evidence, such as curriculum development.

Thinking about what else the evidence might mean for those who use it

There is a considerable amount of time and energy in various places currently being spent on creating a language and set of common practices related to fidelity of implementation of CPDL from, for example, the Education Endowment Foundation. Much of what we have learned from our evidence review here would seem to fit with this. But, while it is not a completely unhelpful way to think about what this evidence is saying about leaders’ work in commissioning and supporting CPDL, the relationship between the two is complex, and not all of this review’s findings validate the way “implementation” is discussed.

The key difference lies in the focus. The majority of the discussion around implementation focuses on questions about fidelity – what is in place to make sure that the CPDL which actually happens is faithful to the “ideal” version of it which its designers intended it to follow. However, the core message of the systematic research evidence is that this runs the risk of getting the cart before the horse – the really important question when it comes to how CPDL is structured in order to make its way into schools is “how does this design address the needs of teachers and learners - practical, theoretical, cognitive and personal?”

The call for coherence emerging from the research evidence is about ensuring that professional learning is connected to the real-world environment, i.e. the school and its classrooms, in which its content has to be deployed. If the system can make this a routine question, which leaders of learning are able to ask and providers are able to answer in clear and powerful ways, then there is good reason to believe that CPDL can be used to solve, rather than create, headaches for senior leaders.

Summarising the key messages:

Research evidence tells us that:

- Teachers can and should identify ambitious aspirations for pupil wellbeing and achievement and seek to understand how their own professional learning – both theoretical and pedagogical – supports those aspirations to be achieved. Teachers bring CPDL to life in their local context when they are supported by leadership and headteachers.

- To ensure that CPDL is effective, whether leading, supporting or commissioning CPDL, school leaders should start with the perspective of shared responsibility: everyone is an important participant in ongoing learning. Positively engaging with professional learning should be threaded throughout the school culture.

- CPDL can be practically and cognitively demanding. As such, systems in place should be able to manage complexity and support sustainable growth. CPDL which ultimately builds coherent learning experiences can help schools in meeting the challenges that the pandemic, economic and regulatory environment has brought to the fore of education.

References

a. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ 2019 annual report on education spending in England, total school spending per pupil in England had fallen by 8% in real terms between 2009-10 and 2019-20.

- Cordingley, P.; Higgins, S.; Greany, T.; Crisp, B. Araviaki, E.; Coe, R. and Johns, P. (2020) Developing Great Leadership of Continuing Professional Development and Learning. CUREE. https://tdtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/DGT-Summary.pdf

- Cordingley, P.; Higgins, S.; Greany, T.; Buckler, N.; Coles-Jordan, D.; Crisp, B.; Saunders, L.; and Coe, R. (2015) Developing Great Teaching. CUREE. http://www.curee.co.uk/files/publication/%5Bsite-timestamp%5D/Developing%20Great%20Leadership%20CPDL%20-%20final%20summary%20report.pdf

- Robinson, V. and Hohepa, M. (2009) School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why: Best Evidence Synthesis. New Zealand Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2515/60170