Supporting students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) requires a shift from traditional behaviour management strategies to more student-centered approaches that foster self-agency, emotional regulation and resilience.

SEND students can take ownership of their emotions through the social, emotional and academic development (SEAD) framework. By embedding neuroscience-backed strategies such as dual processing theory, the Circle of Control and movement-based self-regulation, educators can create environments where students feel seen, heard and capable. As demonstrated in real-world contexts, these methods foster lasting emotional growth and self-agency in the classroom.

SEAD, Dual Processing and the Circle of Control: A Neuroscience Perspective

The social, emotional and academic development (SEAD) framework aligns with whole-school wellbeing initiatives and inclusive education policies. Schools that embed SEAD principles create environments where emotional regulation becomes a daily practice, benefiting all students – especially SEND students.

Neuroscience reinforces these principles through dual processing theory, which helps explain why students may struggle with self-regulation and decision-making.

Understanding Dual Processing and Emotional Regulation

Students with SEND often experience heightened responses in emotionally charged situations due to differences in executive functioning, sensory processing or cognitive processing speed. To help them navigate these challenges, we can use the Circle of Control to shift their thinking from System 1 (reactive) to System 2 (reflective), giving them the space to respond rather than react.

Bridging the Gap: Using the Circle of Control to Strengthen Self-Regulation in SEND Students

Neuroscience research, including Kahneman’s (2011) work, shows that our brains process information through two systems:

System 1: Fast, automatic and emotionally driven, this system operates instinctively, often relying on learned patterns and gut reactions. Many students with SEND, especially those with processing delays, experience a dominant System 1 response when faced with challenges. Instead of engaging with a task, they may shut down or act out – refusing to start, becoming distracted or expressing frustration through disruptive behaviours.

These responses are not intentional misbehaviour but rather a sign of cognitive overload, where the brain perceives the task as too difficult, confusing or overwhelming.

System 2 Slower and more deliberate, this system is responsible for cognitive processing, reflection and problem-solving. It is where self-regulation, flexible thinking and executive function skills come into play. However, many students with SEND require structured support to engage System 2 and sustain focus on a task. Without intentional scaffolding, they may remain stuck in avoidance mode, unable to transition from frustration to problem-solving.

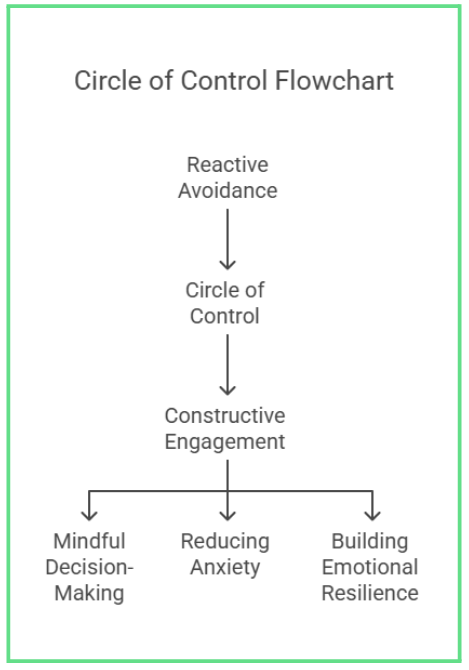

This is where the Circle of Control serves as a bridge, helping students shift from reactive avoidance to constructive engagement.

The Circle of Control: A Cognitive Anchor

The Circle of Control is a simple but powerful tool that helps students differentiate between what they can control (their actions, choices and mindset) and what they cannot control (the difficulty of a task, external expectations or changes in routine). By guiding students to focus on what is within their control, this approach fosters self-awareness, emotional regulation and confidence in problem-solving.

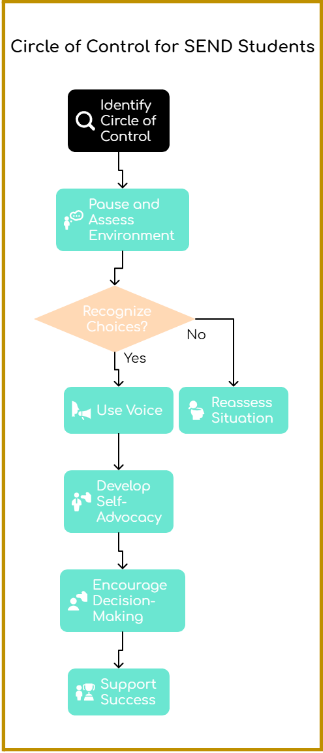

For students with SEND, the Circle of Control provides an essential pause button, helping them learn to assess their surroundings, recognise their choices and use their voice. This process is the first step toward self-advocacy – an essential skill for long-term independence. Instead of reacting impulsively, shutting down or acting out, students gradually learn that they have the power to make decisions that support their success.

How the Circle of Control Supports Self-Regulation

1. Breaking the Avoidance Loop

Many students with SEND experience task avoidance in System 1 when faced with something that feels too hard, confusing or overwhelming. Their brain instinctively shuts down or triggers off-task behaviours because they don’t see a clear path forward. Some may completely disengage, staring at their paper or refusing to participate, while others may act out, becoming disruptive or attempting to leave the situation. This isn’t a reaction to a threat, but rather cognitive overload – a feeling of being stuck without the tools to proceed.

The Circle of Control helps break this loop by prompting students to pause, assess their surroundings and consider their choices. As discussed in Phillips (2025), this strategy empowers students to transition from reactive responses to problem-solving, fostering long-term emotional regulation. Instead of disengaging or acting out, they learn to identify what they can control, such as asking for clarification, using a strategy they know, or breaking the task into smaller, more manageable steps. This shift encourages System 2 thinking, promoting problem-solving rather than avoidance.

2. Encouraging Mindful Decision-Making and Student Voice

Instead of reacting impulsively – shutting down, refusing to work or becoming distracted – students learn to pause and recognise their choices. They begin to understand that they have a voice in their learning experience and that their decisions impact their outcomes. This process builds confidence and lays the foundation for self-advocacy, helping students communicate their needs and take ownership of their learning.

3. Reducing Anxiety by Shifting Focus

Many students with SEND struggle with anxiety, particularly when tasks feel uncertain or unpredictable. When overwhelmed, they may default to avoidance behaviours, either by shutting down or becoming disruptive. The Circle of Control helps redirect their focus to something manageable, creating a sense of stability and reducing stress-driven reactions.

4. Building Emotional Resilience

Over time, repeated practice with the Circle of Control strengthens students’ ability to self-regulate. They develop a growth mindset, recognising that while they cannot always change a situation, they can choose how they respond. This skill is essential not only for academics but also for navigating challenges in daily life.

Practical Strategies for Implementation

- Visual Supports: Display a Circle of Control chart in the classroom and provide individual copies for students to personalise.

- Guided Reflection: When a student becomes frustrated, guide them through a quick reflection – ‘Is this something I can control?’ – to encourage self-regulation.

- Anchor Phrases: Teach self-talk strategies such as ‘I control my effort’ or ‘I can take a deep breath and try again’.

- Role-Playing & Scenarios: Engage students in structured role-play situations where they practice identifying controllable versus uncontrollable elements in different challenges.

- Encouraging Student Voice: Create opportunities for students to express what they need to be successful, whether through self-reflection sheets, check-ins or structured conversations.

Example: Fire Drill Scenario

Consider a fire drill scenario where a student with autism covers their ears, another yells in distress, and a third refuses to move. Meanwhile, a student with anxiety starts breathing rapidly and becomes visibly tense, worrying about whether they are doing the right thing or if something bad might happen. Their System 1 response is immediate and emotional – fear, overstimulation or confusion.

By incorporating the Circle of Control, the teacher can remind them:

- ‘We can’t control the noise, but we can control how we respond.’

- ‘We can use noise-cancelling headphones.’

- ‘Let’s focus on following the teacher’s directions, it will be okay.’

- ‘Let’s remind ourselves that this is just a practice scenario and that we are safe.’

For the student with anxiety, guiding them to identify what is within their control – such as taking slow breaths, counting to ten, focusing on their steps, or holding a calming object – can shift them into System 2: taking a pause, thinking, helping them feel more in control of their emotions in that moment. Over time, these small shifts turn self-regulation into a habit, not just an occasional success.

For students with SEND, self-regulation doesn’t just happen; it needs to be explicitly taught and reinforced. By embedding the Circle of Control into daily practice, educators create a cognitive bridge that helps students shift from task avoidance – whether through shutdown or acting out – to problem-solving.

With time and consistency, this approach builds confidence, resilience and self-advocacy, giving students the tools to navigate challenges with greater clarity and control.

The long-term impact? This is the first step toward self-advocacy.

Embedding SEAD and Neuroscience into School Culture

To ensure emotional regulation is not treated as an isolated support system, schools should:

- Implement Mindfulness and Structured Decision-Making Frameworks: Integrate these as daily routines to foster a culture of emotional awareness.

- Provide Staff Training: Regular training on dual processing and SEAD strategies equips educators with the tools to support emotional regulation effectively.

- Align SEAD Techniques with Ofsted’s Emphasis: Ensure that emotional regulation is a key component of personal development and behaviour management.

- Develop Consistent School-Wide Language: Use phrases like ‘Pause and Process’ or ‘Reset and Reflect’ to create a unified approach to emotional regulation.

Expanding Implementation: How Educators Can Embed Emotional Regulation School-Wide

To make self-regulation strategies sustainable, they must be embedded across the entire school culture. Below are detailed steps educators can take to make SEAD integration effective and scalable.

Whole-School SEAD Integration

- Staff Training on SEAD & Dual Processing: Conduct regular professional development sessions for educators and staff to deepen their understanding of SEAD, the Circle of Control and dual processing theory. Providing hands-on activities and case studies will equip educators with practical strategies to integrate emotional regulation into daily teaching practices.

- Consistent Language Across Classrooms: Implement a unified approach by ensuring that all educators, from primary to secondary levels, use consistent language when guiding students in emotional regulation. Phrases such as ‘Pause and Process’ or ‘What’s in your control?’ should be reinforced across classrooms and school environments to create a culture of self-awareness.

- Integration with School Policies: Embed SEAD principles into behaviour management policies, restorative justice frameworks and academic intervention strategies. Schools should align these practices with positive behaviour reinforcement models, ensuring that emotional regulation is seen as a key component of student success.

- Cross-Departmental Collaboration: Encourage collaboration between general education teachers, special education staff, school counsellors and administrators to develop a holistic approach. SEAD strategies should be discussed in staff meetings and interdisciplinary teams should work together to create personalised self-regulation plans for students in need.

- Family and Community Involvement: Host workshops for parents and caregivers to provide them with tools for supporting self-regulation at home. Engage the wider school community by integrating SEAD into school-wide events, newsletters and student leadership programmes.

Creating Emotionally Safe Learning Environments

- The 90-Second Pause School-Wide: Introduce a universal strategy where students pause, breathe and process their emotions before reacting. Teaching this habit across all grade levels ensures that students have a consistent, structured way to reset when faced with challenges.

- Calm-Down Zones in Every Classroom: Designate quiet, sensory-friendly spaces where students can regulate emotions without stigma. These areas should include comfortable seating, stress-relief tools, fidget items and visual calming strategies.

- School-Wide Regulation Breaks: Implement structured mindfulness or movement breaks throughout the day to encourage self-regulation. Activities such as deep breathing exercises, guided stretching or sensory walks can help students reset and refocus.

- Visual SEL Cues: Use posters, charts and digital reminders in hallways, restrooms and common areas to reinforce emotional regulation strategies. Colour-coded emotional zones or interactive visual boards can help students identify their emotions and choose appropriate coping strategies.

- Flexible Seating Arrangements: Offer a variety of seating options, such as standing desks, wiggle cushions and quiet corners, to accommodate students’ different sensory and attention needs while promoting emotional regulation.

- Staff Awareness and De-escalation Training: Train teachers and staff to recognise early signs of emotional distress and employ proactive de-escalation techniques. Techniques such as active listening, non-verbal cues and personalised coping plans ensure that students receive the right support before behaviours escalate.

Conclusion: Empowering Students to Thrive

By embedding SEAD strategies into daily routines, whole-school policies and peer-supported initiatives, educators can create a learning environment where every student is empowered to thrive not just academically, but emotionally and socially. This approach fosters a future generation of independent, self-aware individuals who have the tools to navigate life’s complexities with confidence and resilience.

Helping students build emotional regulation isn’t just another classroom strategy; it’s the foundation for their success both in and beyond school. Empowering students in this way doesn’t just help them; it strengthens the entire school community, creating a culture of resilience, understanding and real growth. Like all students, those in special education face challenges – and they need tools that help them grow, not just get by.

The Circle of Control is not about managing behaviour but giving students the confidence and skills to regulate emotions, make choices and navigate life with independence. When we move from control to empowerment, we create a space where every student has the chance to build resilience, succeed and feel capable of handling whatever comes their way.

Donna Lynn Germano Phillips, M.Ed., is a SEAD Champion with Mindful SEAD as well as a licensed SEAD Specialist, Autism Mentor and leader in SEL and Special Education. She serves on the Nevada State Superintendent Teacher Advisory Cabinet (STAC) and is a national speaker and published writer. As a Self-Contained Special Education Coordinator and Lead, she specialises in fostering emotional regulation and self-agency in students with SEND. She has also led national Mindful SEAD Summits, supporting educators in integrating SEL and SEAD strategies effectively.

References

Phillips, D. (2025). Building Resilience in Special Education: The Circle of Control. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/building-resilience-special-education-circle-of-control

Covey, S. R. (1989). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Free Press.

Ofsted (2019). The Education Inspection Framework: How Ofsted Inspects Schools. Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development (2019). From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope. The Aspen Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/aspen_final-report_execsumm.pdf

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (n.d.). What is SEL? Retrieved from https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month