There is a problem in student wellbeing, and the data say so. Dulwich International High School Zhuhai chose to develop a coaching culture in our aspirations to address student wellbeing. We believe this is in keeping with our broader, underpinning, intention to develop student agency and collective teacher efficacy.

Dulwich College International’s Education Team have been working with the wider group of schools in the network, taking an evidence-based approach, and giving considerable thought to how student agency (broadly giving greater voice, choice, influence, ownership and autonomy to students in determining and co-constructing their own learning) can be developed and harnessed through school review. Sian May, Director of Senior Schools, said:

As a priority, teacher and school leadership wellbeing is paramount. Countless studies acknowledge that when educators and other school staff experience manageable stress levels, and social and emotional competency, their collective efficacy and capacity to support positive relationships and social and emotional learning for students, will increase.

The suggestion is that if we are to build student agency, and to enhance student wellbeing (we think there is a correlation between these), then we have to develop capacity for doing so through specific leadership approaches.

Our school

Dulwich International High School Zhuhai is part of the larger Dulwich College International group of schools. As a High School, our students typically join us at the age of 14 years old, having completed 9 years of compulsory Chinese education.

Families ‘opt out’ of the Chinese education system, preferring a more western and holistic education philosophy, and having clear aspirations for their son or daughter to attend a top ranked university in the west. We have circa 350 students, studying UK based internationally recognised qualifications – the IGCSE, and also the AS and A level qualifications.

With most of our students coming from the mainland China, we are very much an international school with international staff, working In an entirely EAL (English as an additional language) environment.

School level action

There has been some thought-provoking research and analysis about wellbeing in schools and it is school leaders who are tasked with actually doing something about it. The challenge is ‘what is that right action?’ What might be the consequences of getting it wrong, as well as the positive impact of getting it right? And given the relative choices identified, what are the opportunity costs?

We faced these questions during a review of our School Improvement Plan in 2018. We were aware that, as a High School, our students existed in a context of ‘heightened expectation and aspiration’ – after all, all our students are sitting external high stakes exams at some point in the year. They come to us because their parents want them to study at some of the best universities around the world.

In this context we set about building capacity towards what we referred to as ‘Deep Support’2, a term coined from the personalised learning series spearheaded by the SSAT in the UK. This had explored the relationship between mentoring and coaching, and advice and guidance programmes in schools, and how they might provide a more personalised experience for students.

We wanted to enhance our pastoral support by ensuring that our staff were trained in advanced-level coaching techniques so they were able to use coaching techniques in their pastoral interactions with students, especially those related to wellbeing.

Coaching was chosen as a ‘tool’ for a number of reasons. I had for some time believed in the power of coaching as a professional development and leadership tool. As a senior leader in schools it had been one of my ‘go to tools’ when engaging with colleagues. I had received coaching myself and become an advanced level coach after training from Making Stuff Better (https://www.makingstuffbetter.com/) I was increasingly convinced of its effectiveness in exploring distilling and clarifying issues , and then developing actions to address them.

Additionally, research seemed to indicate that self-determination was a key characteristic in supporting student’s progress. The EEF Toolkit4 showed that ‘meta cognition and self-regulation’ are highly influential in supporting student’s progress. Whilst the focus here is on self-reflection in learning, it is clearly associated with the coaching model.

The question we had was whether this as the right choice? What might the other options be? Certainly, there were many questions left unanswered and a sense that whilst this ‘felt’ like the right direction we could not be sure.

What we did

Back to our question – how do we support and empower students to be better able to manage and deal with the pressures that come from being in a high stakes environment and deliver our aspiration to improve wellbeing?

We set about identifying a ‘provider’ that understood our context and needs and could support us in an enhanced approach to developing capacity. There was some in-house experience of coaching but it was evident that there were a number of advantages in accessing ‘outside’ expertise.

As an international school in China there are some contextual considerations. On-site professional learning was of course possible. However, we needed to give consideration to virtual access too.

A one-off course for a day or two might create some momentum and interest, but this was likely to wane over time as the realities and priorities of life in school ‘took over’. We also wanted to work with a team that understood an education/ schools’ context.

Our sense was that ‘coaching for performance’, as you might see in a business context, just wasn’t the right fit for our purposes.

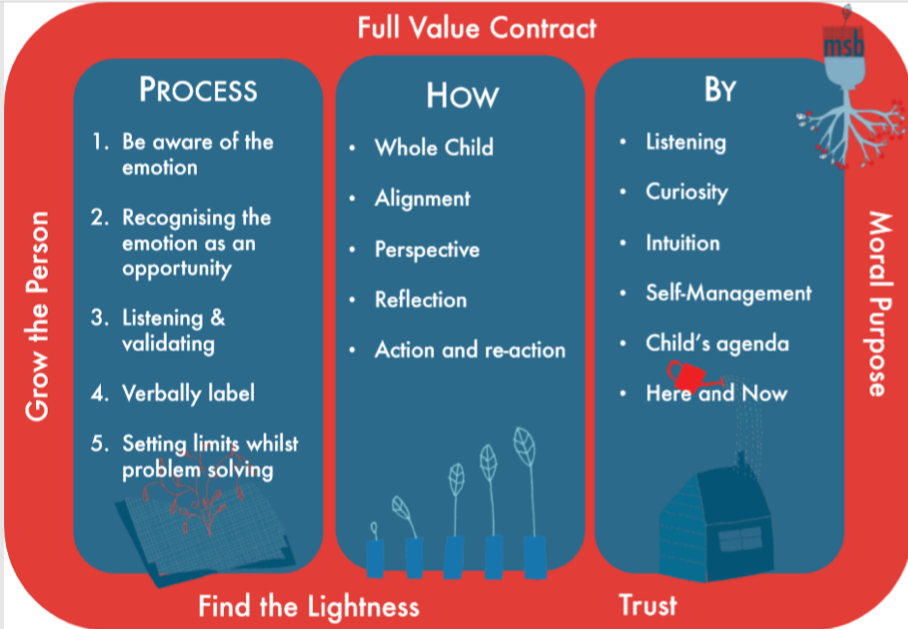

MSB Emotional Coaching Model

We were able to build a programme with UK-based Making Stuff Better6, that allowed us to achieve the blended delivery model we were after. A ‘kick off’ two-day workshop in November 2018 was planned to really build buy-in, gain traction, immerse participants early on in the practice of (as opposed to the study of) coaching.

This was followed up by monthly virtual sessions that would be used to i) reinforce and consolidate existing skills practice, ii) address participant-specific case work queries (“I am working with a student and would like your advice/ perspective on taking XYZ forward….”), iii) introduce new skills so participants feel a continuing sense of progression, iv) maintain frequent ‘touch points’ so participants feel an ongoing sense of commitment and association with the programme.

12 participants joined the programme, which was completely ‘opt-in’ and elective. These ranged from teaching staff to professional support staff (all student facing), expat, local bi-lingual, and also expat but with Asian heritage.

Virtual sessions were arranged into two sub-groups based on the practicalities of ‘availability’ and a recognition of the benefits of a more ‘intimate’ and personalised virtual experience.

What we have found

- The programme was very well received as a professional development opportunity. Participants were almost universal in acknowledging how this has enhanced their skills in leading pastoral interactions with students that are focused on wellbeing.

- An outcome of this has been a heightened sense of shared experience and mutual support. Discussions have naturally led to a consideration of how we address staff (not just student) wellbeing and this is welcomed given the desire to move to having a truly wellbeing culture in school.

- Additionally, there has been a sense of enhanced staff agency, as participants seize the opportunity to offer feedback to our leadership team, and are afforded the opportunity to shape and co-construct the next phase of this work.

- Critically, there is a collective belief in the potential beneficial impact of this work on student support in the wellbeing context. There have been some challenges, and these are outlined below, but the benefits of collective teacher efficacy are clearly evident from both the practice we have seen, and the feedback we have received.

In implementing the programme, we were conscious of the importance of choice.

When launching our ‘Wellbeing Coaches’ programme we looked for a blended model; whereby coaches could be accessed based on a ‘staff-referral’ model, or where students might request access to a coach (‘self-referral’). Having 12 trained coaches, we were able to add greater choice, with the option of which coach the student might prefer to work with (‘elective-referral’).

But issues have emerged!

- Choice does not necessarily equate to opportunity: Initially, not all our coaches were able to immediately engage directly in a coaching interaction; partly because those with more evident ‘pastoral positions’ (such as Head of Year) had more frequent opportunity to support interventions and were able to use their coaching skills more readily.

- Ignorance is not bliss: A clear reflection from participants is that this work was important and that all stakeholders (and particularly staff) needed an enhanced understanding of what our coaching programme was. This was because it was accessed on the basis of staff or student (self) referral. Effectively, not being fully aware of the offer, they did not see the opportunity.

- Cultural context is key: participants report that some students found it difficult to articulate their feelings / understanding of the issue they wish to address whilst being coached.

- There is a sense that ,culturally, exploring ‘feelings’ and sharing these is not something that sits as ‘normal’ or practiced in Chines culture. Some suggested that students demonstrated an inhibition build around a concern of ‘loss of face’.

- Trust me, I’m a professional: we know our students trust us, they tell us so in our stakeholder survey. Trust is the cornerstone of a successful coaching relationship. n Asia trust is built up over time, quite a long time in fact. Whilst deference and respect are given to those in ‘authority’ this is clearly not the same as trust. As such, it can take quite a time to build a trusting and productive coaching relationship.

- ‘Students come first’: in our school, and in the wider Dulwich College International family of schools, we live by the mantra ‘students come first’. The aspiration for this wellbeing coaching programme was to positively impact the lives of students in support of their wellbeing through our pastoral interactions. However, an unintended yet positive consequence of this training has been a heightened sense that we can build a stronger culture of wellbeing (and a coaching culture for that matter) for all in our school. We are moving towards a ‘people come first’ mantra in some ways as trained coaches have found themselves using their new skills with colleagues too.

- Answers and outcomes, rather than process and self-discovery: If schools are the place students learn, it stands to reason that they might expect to be given the answers in such a place. Of course coaching is not like that, being built on the coachee bringing their own questions and being supported to find their own answers. As such students have been drawn to seeking options and suggestions, much as you’d expect through a mentoring approach.

- Blurred lines and a ‘can of worms’: One can see this work as part of a much wider system of support. Our wellbeing coaches have engaged in interventions that, at times, have ‘unearthed’ deep rooted and quite unsettling childhood experiencest is clear that the ‘pastoral concern’ that was the catalyst for a ‘wellbeing coaching intervention/ referral’ has begun to uncover an experience for which our coaches are not trained nor able to support – coaching is not ‘social emotional counselling’.We need to be clear that this work is not a replacement nor substitute for professional therapeutic support by highly trained and qualified practitioners.

- “Do ya get me?” / the wrong garden path: Having worked in the UK education system for more than 20 years there are times when the nomenclature of a teenager can present a challenge or two. All our students are EAL (English as an Additional Language) and are being asked to share quite complex emotional ideas in a language that is not their native tongue.It is no surprise that there are limitations in what can be achieved through an English medium coaching intervention. Not only can a student’s ability to articulate meaning be a challenge, but the ability to understand subtlety and nuances of a question posed by the coach, can present a limiting factor. Moreover, language is not simply a case of ‘direct translation’. It is very clear that language is rooted in cultural references and mores. As such, the complexities of this are significant.Seeds take some time to germinate: it is the belief of some of our coaches, and notably amongst our local bilingual participants for whom we believe have most relevant insight, that students are becoming more receptive to this type of support. This is heartening as we move towards the development of the programme (see below)

- By students, for students: a key characteristic of students in our school is that they are very considerate and caring of and for each other. We have exposed a small group of students to a coaching programme to establish their perspective.

It seems that there is a potential appetite for this amongst them. Could this be a way to support greater student agency in this area? One noted: “I think that would be better if more students can get to know about coaching….. putting it into the PHSE course is also a good idea”

What next

Advanced level coaching for existing coaches – it seems sensible to build in this area. This will allow us to explore a ‘train the trainer’ / ‘cascade’ model and build a more sustainable model over time

Cohort 2 – additional coaches – we need to build more capacity, extend this as a whole school approach. Critically, to address the challenges we have faced in terms of our EAL and cultural context, we believe it right to extend this programme to engage more local bi-lingual staff. T

This will, we believe, not only address the challenges noted above, but will give us greater capacity to focus on and build staff agency and wellbeing.

Coaching skills for students – given the feedback we have had from students, we have explored the design of a unit of work in a developing PSHCE programme that is built around understanding the triggers and feelings associated with stress and the ‘tools’ that can be used to self-regulate and manage these. Necessarily, a coaching element will form part of this –linked to a programme called the Inner Leader Programme.

(https://www.makingstuffbetter.com/programmes/the-inner-leader-programme )

Cultural competence – as part of this reflection we have been able to recognise that cultural context (our students having, broadly, a Chinese upbringing) influences how students engage in the school’s culture – a western philosophy build around the traditions of a holistic education- requires greater understanding. We will be looking to have our expat coaches work more closely with our local bi-lingual trained coaches to support this cross fertilization of ideas, perspectives and practice.

Coaching communication – we need to ensure that key stakeholders better understand the programme, its purpose and the opportunities that it represents. In this way we hope that it will be seen as ‘the way we do things around here’ i.e. genuinely part of our school culture.

Andrew Macdonald-Brown is the Director of Dulwich International High School Zhuhai

References

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/student-agency-what-good-sian-may/

- http://www.redesigningschooling.org.uk/campaign/background/

- https://uk.coactive.com/

- https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit/

- https://www.makingstuffbetter.com/

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month