Project Zero was given its name in 1967 by its founder, philosopher Nelson Goodman, who quipped that there was little, if any, systematic knowledge about thinking in the arts – hence the name Zero. In this essay, I tell the story of arts research at Project Zero from the early 1970s until today, focusing on four strands of research: developmental studies of children’s artistry; our move into arts education and assessment with Arts PROPEL; then a move into wider analyses of others’ research, which led to the debunking of popular claims about the outcomes of arts education; and most recently our ethnographic study of the habits of mind that are actually taught (and we hope learned) in visual arts education, culminating in our Studio Thinking framework of visual arts education. We now have a considerable body of knowledge about thinking in the arts and a secure foundation from which to move forward to new initiatives.

Developmental Trajectories in the Arts

While most developmental psychologists (influenced by Piaget) have focused on the development of logical and scientific thinking, at Project Zero we have focused on the development of artistic thinking. We have studied the beginnings of metaphor, drawing, music, and pretend play (a precursor to metaphor and to acting). One of the most intriguing findings to come out of this research was that of the ‘U-shaped curve’ in artistic development.1 Most capacities studied by developmental psychologists simply get bigger and better with age. But occasionally, one sees a decline or disappearance after the early years of childhood, followed by a reappearance (in some or all individuals) later on.

A ‘U’ had already been demonstrated by child language researchers who noted that, for example, children who utter an incorrect form of an irregular verb in the past tense (I goed) had actually been using the correct form (I went) a few months earlier.2 Ultimately, of course, they revert to the correct irregular form. This sequence demonstrates rule learning: at first young children have memorised a small set of irregular verbs and thus utter them correctly. Later they master the ‘add an –ed’ rule and overgeneralise this to irregular verbs – and thus ‘I goed’ actually represents a cognitive advance, even though it seems on the surface like a regression. When transitioning from goed to went, children have retained the –ed rule but now know when to apply it and when not.

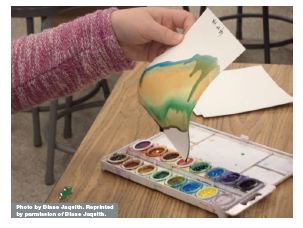

We documented a U-curve in the arts, also explainable by the acquisition of the rules of the domain. Children’s drawings at age 3–5 are wonderfully inventive and aesthetic, often reminding us of 20th-century paintings by artists such as Paul Klee or Joan Miro. At an early age, children do not care if they paint the sun green and the sky purple, and that is what so charms us (or at least those of us familiar with 20th-century Western art).

During the elementary school years, children enter what we dubbed the ‘literal’ stage. Children around 8, 9 or 10 become preoccupied with learning the rules of the drawing domain. They strive for realism and as a result, their drawings look conventional and far less interesting to us. Later, especially for those who go on to become artists, adolescents are willing to break these rules that they have established, drawing in a non-realistic, surrealistic or abstract style.