The accountability machine sucks the life from schools and pupils and makes Year 6 a bizarre and unbalanced final year in primary for millions of children. When accountability measures are the main measures of success, schools and staff work increasingly long hours to meet those targets. The current system of accountability is unfair on all schools but it is especially unfair on schools serving disadvantaged communities.

The impact of “chasing the targets/accountability measures” has seen thousands of teachers and school leaders leave the profession for reasons of principle and their own health and wellbeing (a third of new school leaders leave the position within 1-3 years of starting).

What is now clear, thanks to the Schools Minister’s candid approach with the Education Select Committee, is that the SATs have nothing to do with the children and essentially the pressure our children feel is purely to provide the government with data for school accountability. As professionals with the care and wellbeing of our pupils at the very core of what we do, we must ask ourselves if this is right.

Crisis

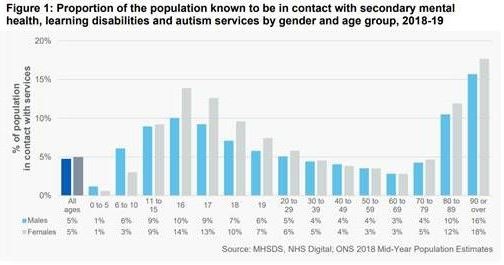

Referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services are at record levels. One educator in a NW Council area said that there were 1000 pupils not receiving the support they needed each year in his town. This chart demonstrates the scale of the problem.

Is it little wonder that the EPI report Access to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in 2019, finds a stark gap between available support and the needs of the estimated 1.25 million children and young people who have a diagnosable mental health condition:

- Only 1 in 3 children with a diagnosable condition are accessing treatment.

- In 2018-2019, approximately a quarter (26%) of children and young people (CYP) referred to specialist mental health services were not accepted into treatment.

- If we apply this to the number of children and young people accessing NHS funded community mental health services in 2018-19 reported by NHS England, it is estimated that approximately 132,700 children were referred for but not accepted into treatment.

A possible solution

During lockdown many educators questioned the way things were done and the impact it had. The vast majority of school leaders think it’s time for change. What Covid has taught us is that we need a 'quality of life' response incorporating physical and mental wellbeing. This would be one of the twin tracks to school improvement, alongside high quality teaching and learning.