A feature of 2017 has been the frequency with which reference has been made to “fake news” in the reporting of current affairs stories. Fortunately, the concept is not difficult to pin down. Speaking on the BBC radio programme Law in Action (2017), Magnus Boyd defines “fake news” as “false reporting, inaccurate content but dressed up as real news”. Joshua Rozenberg adds that it is “content deliberately designed to misinform and mislead”.

Earlier this year, concerns over “fake news” in the online environment especially became so great that Facebook felt prompted to circulate ten tips for identifying instances of the phenomenon, which became widely publicised (Sulleyman, 2017). Such action perhaps implies that “fake news” is a modern problem. In truth, though, the term itself may be new but very often in the past what we would now regard as “fake news” was labelled “disinformation” or “propaganda”.

The importance of young people appraising information rigorously has long been championed. Over two decades back, Wray and Lewis (1995) wrote, children “will constantly come across examples of misleading, incorrect, intentionally or unintentionally biased information, and they need to know how to recognise this and what to do about it” (p. 8). Many of the tips Facebook offers for exposing “fake news” are comparable to actions that school librarians have been advocating for years when stressing the importance of evaluating information more generally. Some emerged with the development of the Web, whilst others were first practised in the paper environment decades ago. Let us examine each of the Facebook tips in turn and explore the wider or related issues that pupils may be asked to address and have, in fact, considered in the past.

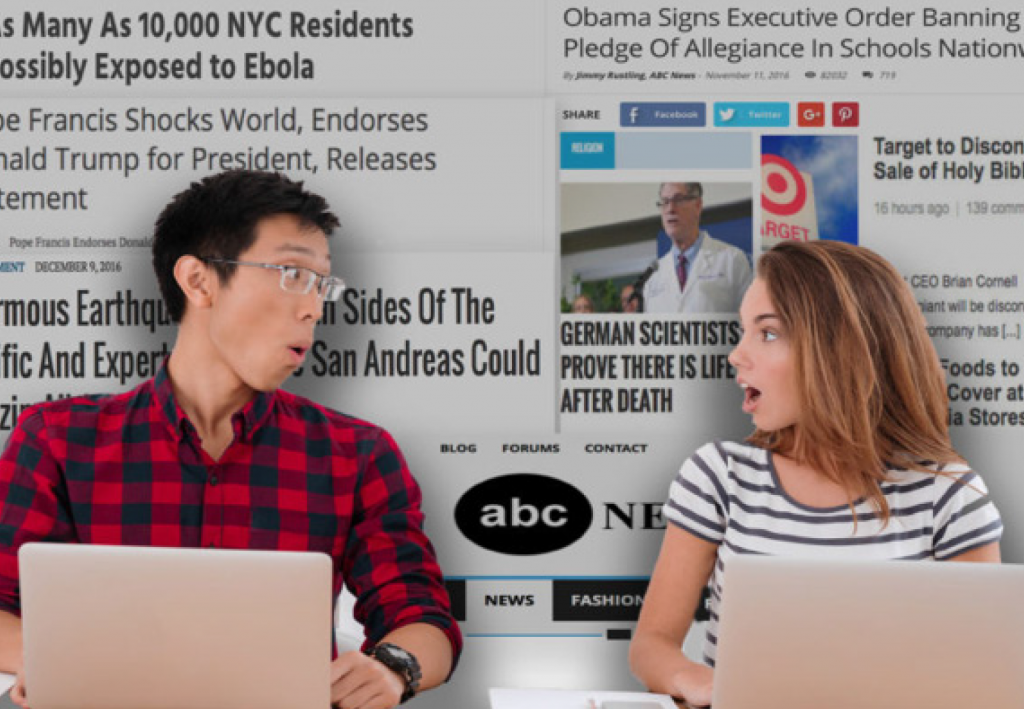

The top ten tips by Facebook for spotting fake news:

1. Be sceptical of headlines

Facebook urges readers to be wary of eye-catching headlines littered with capital letters and exclamation marks, commenting that a headline which looks incredible at first sight is indeed likely to lack truth. Since the earliest days of information skills instruction, teachers have encouraged youngsters to distrust headlines in newspapers. Certainly, newspaper stories should be subjected to the kind of surveying and questioning actions that Dean and Houldey (1997) advocate when outlining the SQ4R approach. These may involve students predicting from the headline what the text will cover, forming questions that they expect will be addressed by the main text and then engaging with the story itself in order to find appropriate answers.

Even if the underlying claim made in a headline is correct, the details of the story may be simplified to such an extent that the headline is misleading when read in isolation. It is generally the case that where a complex event is summarised in a very limited number of words, the matters are reported with such brevity that the published version cannot be trusted on its own, and the reader can acquire no more than, at best, a superficial understanding of the inherent issues. Such concerns are by no means restricted to the current information age. Nearly forty years ago, Burke (1978) warned of the danger that “content is sacrificed for stimulus” in situations where it is assumed that the television viewer will be bored after only a few minutes of air time or the reader after two or three paragraphs (p. 295). In addition to comparing newspaper headlines with the content of detailed reports, teachers can juxtapose the understanding that may be gained, respectively, from abstracts and then full academic papers and consider the brief information provided by the BBC’s teletext news service as opposed to more in-depth accounts. It can be enlightening, as well, to watch a DVD recording of an episode of a particular television series and then read a one- or two-sentence synopsis of the instalment in a programme guide. Surprising frequently it is apparent that the guide either omits any reference at all to a key plot development, thereby skewing the account of the events portrayed, or offers a summary that is so cursory as to be factually inaccurate.