Earlier this year, with my colleagues at the universities of Winchester and Manchester, I published the results of a two-year research project, which we believe has profound implications for the curriculum at all levels within the education system.

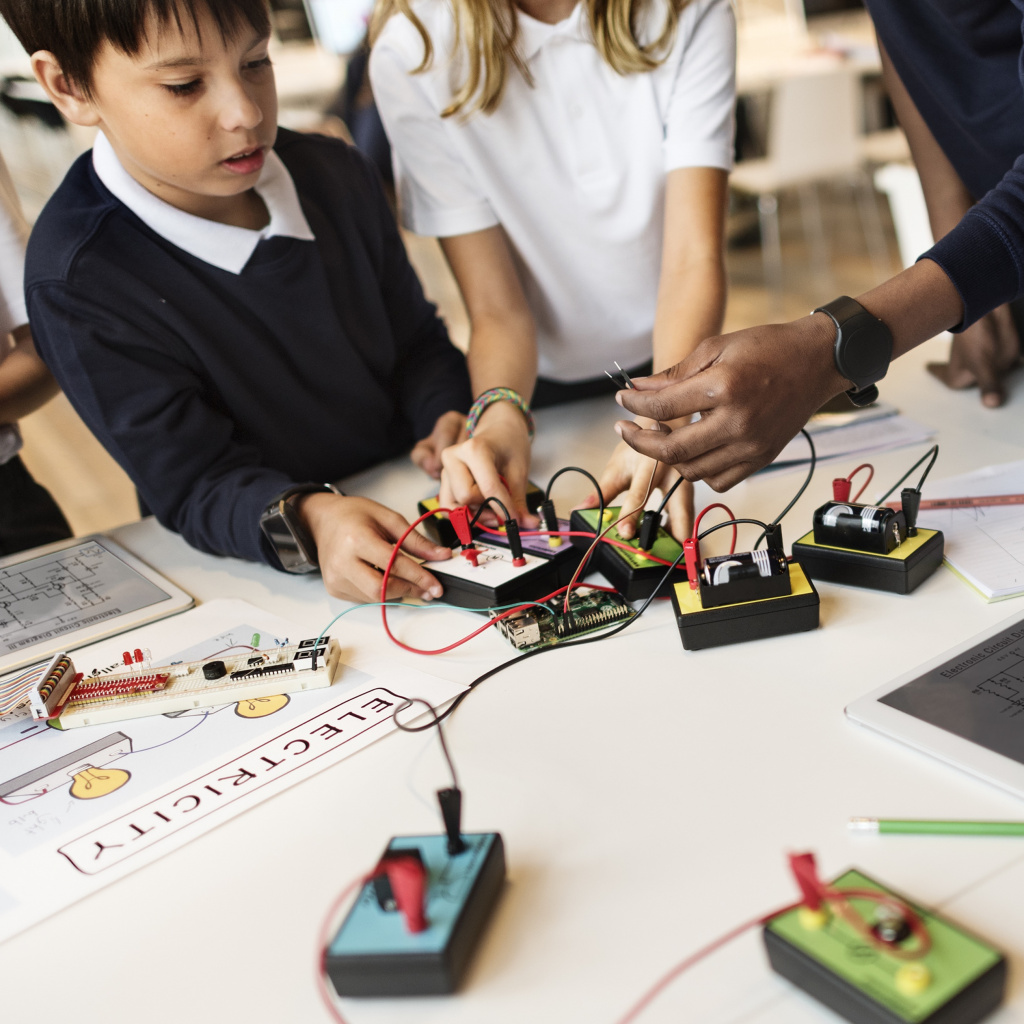

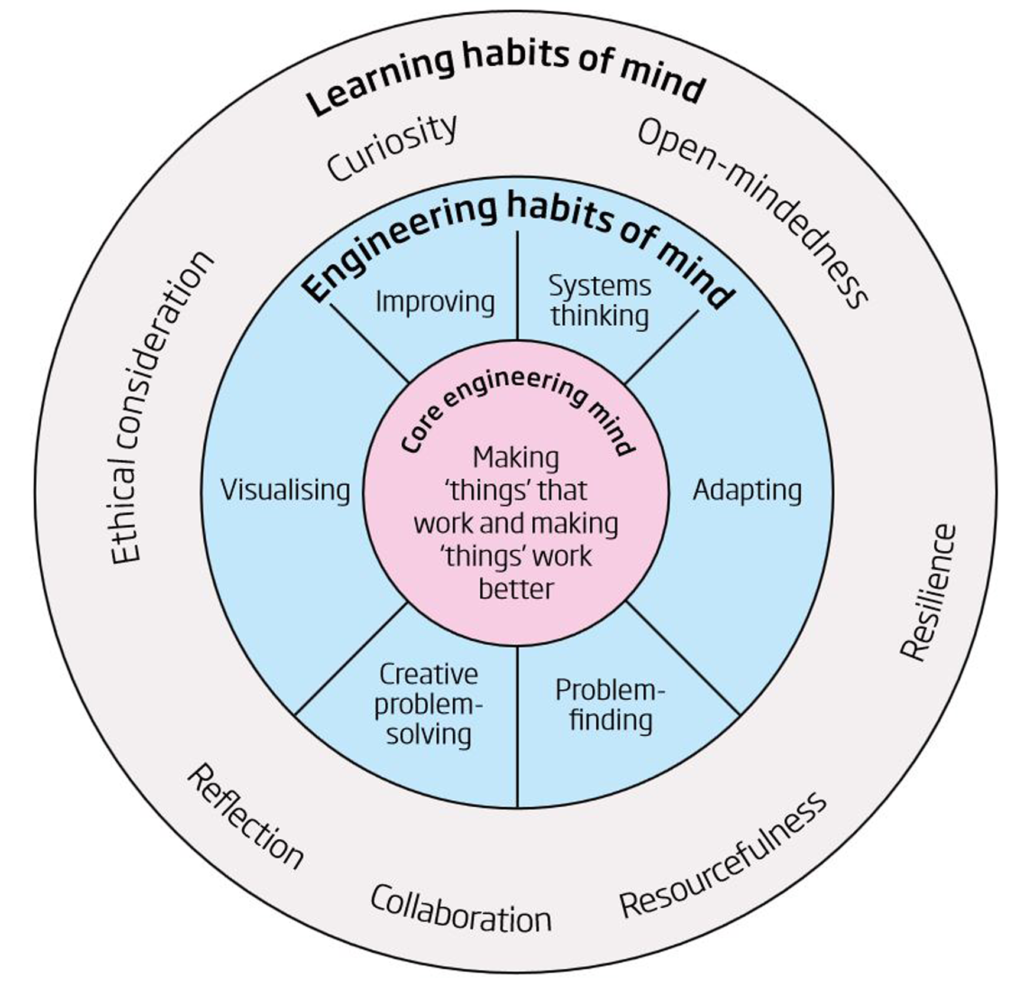

Although it addressed a particular problem, our inability to create, as a nation, enough high-powered engineers, the report Learning to be an Engineer: implications for the education system, found that a new reframing of the curriculum in terms of set of problem-solving habits of mind typically found in top engineers was more important to prioritise than the set of subjects typically associated with engineering, such as maths, physics and design and technology. One of the most effective ways of developing young engineers in schools is a playful experimentation with the use of authentic design processes, a kind of problem-based learning. For the teachers involved, it became obvious that, not only could they deepen their pupils’ knowledge, they could also teach in a way that was engaging, creative and likely to develop young engineers.

Rethinking pedagogy

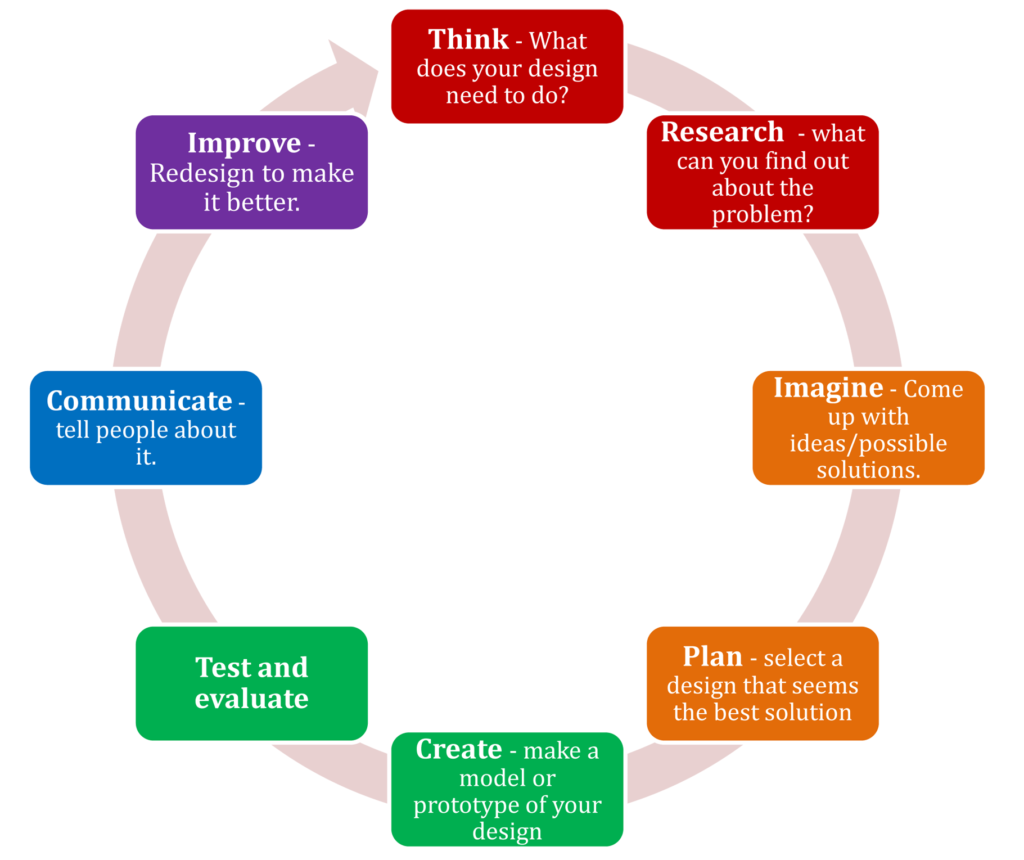

The teachers taking part in our research realised that teaching engineering, like developing creativity, depends at least as much on experimentation and imagination as it does on subject knowledge. They drew on three ‘signature pedagogies’2 - the engineering design process, playful experimentation and authentic engagement with engineers. The signature pedagogies – teaching and learning methods – were selected as those most likely to help pupils think like engineers.

Gomer Junior School in Hampshire, for example, introduced engineering sessions in every year group each Thursday morning from 09.00-12.00. The sessions integrated maths, literacy, science and IT with the aim of motivating learners and fostering understanding of real-world applications of STEM subjects by experiencing hands-on activities, such as The Space Race project featuring Tim Peake’s Principia Mission3, and involved programming Crumble-controlled moon buggies. Underpinning their teaching and learning was a version of the engineering design process, the STEM Wheel.

By contrast, Medway University Technical College (UTC) in Kent focused on raising awareness among staff and students about the six engineering habits of mind, their usefulness and ways of integrating them into the curriculum. Whole-school assemblies were organised around each habit of mind and icons for use on posters and rewards postcards were created. The systems thinking one is shown below.

Medway UTC’s strategies to cultivate awareness of EHoM had an important impact on those teachers in subjects such as art and English, who felt much more included in the overall engineering mission of the school.