This is, of course, not necessarily the case. Experience itself is not enough. Teachers – like children - learn by making sense of experience. And reflective practice can help in this process. Reflection offers educators the opportunity to question, refresh and enliven what they do, to avoid becoming stale and static. But how does one capture reflections? And what is needed to go beyond the cosmetic, surface level – to see what lies beyond the mirror? This second article in the three-part series considers these questions.

Recording reflections

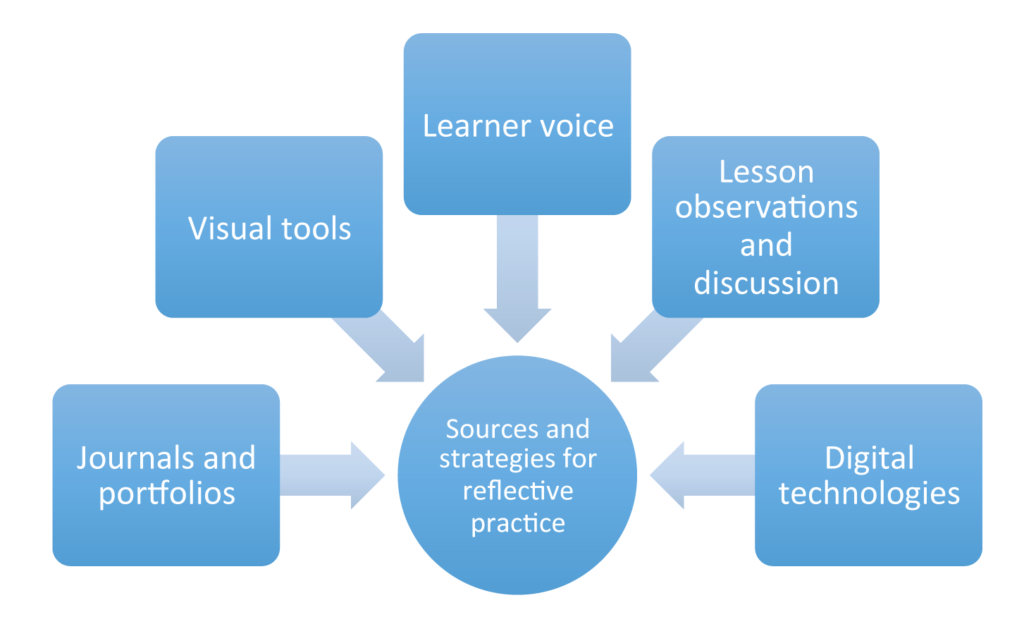

There are various means of recording and supporting reflective practice. The choice very much depends on whether there are plans to share outcomes with others and the available time and resources. More structured approaches are useful for systematically collecting data but these are more time consuming than, say, informal discussions. Figure 1 is not exhaustive but sets out some common contexts, strategies and tools used to record reflective thoughts.

Journals and portfolios

Reflective journals are perhaps the most widely used means of describing change in practice and identifying how this might be improved. Journaling comes in many forms – from impromptu jottings on sticky notes to more structured formats that follow set prompts. Keeping a journal is essentially a linear process but maps and other visuals can be used in a more fluid manner to record connections and relationships between ideas and information. Portfolios are also widely used, particularly in initial teacher training where trainee teachers collect evidence of their progress towards standards for qualified teacher status/ teachers’ standards. In the context of reflective practice, such portfolios can include annotated lesson plans and evaluations, data on learners’ performance and how this has been interpreted, feedback comments from colleagues and examples of professional development. However, the maintaining of such portfolios and other records should not become a chore if the value of reflection is to be realised. The danger is reflection becomes a mechanistic process of compliance.

Visual tools

The power of mind-maps, diagrams, doodles and other visual tools should not be underestimated as a form of stimulating reflective thinking. Once dismissed as an idle use of time, doodling is now recognised in helping people to stay focused, retain information and spur creative thoughts. Sunni Brown, author of The Doodle Revolution, points out that the likes of Einstein, Edison, and Marie Curie were all inveterate doodlers. Similarly, ‘sketchnoting’ is becoming increasingly popular in schools and the business community. Sketchnoting is a strategy to help capture thinking visually, remember key information more clearly, and sharing this in an engaging way. To be able to sketchnote, you don’t require advanced drawing skills, but do need to visually synthesize and summarise via shapes, connectors, and text. In other words, a sketchnote is a personal, visual reflection. In terms of reflective practice, this could provide a starting point for gathering thoughts about a lesson, topic or class of learners. The finished sketchnote also provides a discussion point for use with children – who can reflect on the lesson.

Learner voice

In the first article we introduced Brookfield’s model that offers practitioners different lenses through which to explore what happens in the classroom. One of these lenses, learner voice, has become increasingly important over recent decades in the context of children’s rights. The late Professor Jean Rudduck wrote extensively on the value of listening to learners, particularly in building relationships and more inclusive communities. For reflective teachers, tapping into the rich potential of learner voice has the advantage of seeing their practice from a different, fresh angle (Rudduck and Flutter, 2003). By its nature, reflective practice is inherently subjective. By creating an inclusive environment in which learners and others feel confident enough to speak openly, teachers can gain greater insight into the impact of their work. This does not mean necessarily that learners know better than teachers, nor does it mean treating learner voice as representing one homogenous view. When learners’ views are considered alongside other sources, teachers are able to build up a more rounded picture of what is happening in the classroom. This can help shed light on what otherwise might be missed. Learners can express their views in lots of informal ways, such as jotting down comments on sticky-notes and drawings as well as through class councils and school parliaments, focus groups, newsletters and questionnaires. These can prove an important stimulus for teachers’ reflective thinking.

However, these models rely on personal reflection, which, although valuable runs some risks. How do you know if you are reflecting on the right things to improve the teaching and learning in your class? What if we are unaware of some of our practices – both the good and the not so good? And, of course – what we think we do is not necessarily what actually takes place in the lesson – so how can we ensure that we are reflecting on actual and not perceived events?