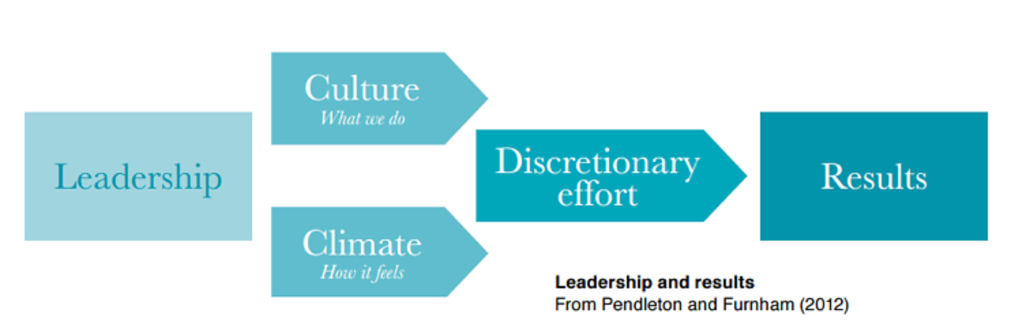

Great delivery in schools doesn’t happen by accident. It is the result of all the staff and pupils working together to achieve a clear set of objectives. To move from a vision or a strategy to strong delivery requires buy-in and focus from the school-wide team. The role of middle leaders in enabling this is critical. They are the people who most directly lead and manage the front line of delivery in classrooms. But as the diagram below summarises, the relationship between leadership and results is not a direct one. Creating the right culture and climate is essential.

Culture and climate

In this model, culture is taken to mean ‘the way we do things around here’ which relates to the systems, procedures and common practices and in particular, to the high standards that exist in the way these are delivered. A useful way of thinking about culture is to consider what someone new joining a team would see happening on a day-to-day basis and the extent to which everyone in the team is working in the same way and to the same level of expectation. Is there a consistent set of high expectations from middle leaders for their individual teams? As a result of this, is teaching and learning of a consistently high quality? Are the learning environments inspiring and well organised? Do pupils have strong and supportive relationships with their peers and all the staff they work with?

Climate is more about how it feels to work in a team. This reflects team morale, how supported and challenged teachers and other staff feel and the degree of trust within the team as a whole. This is much more difficult to describe or measure, but detailed research has shown that the effect of climate on team productivity is considerable (Corporate Leadership Council 2004).

Discretionary effort

Taken together, the more positive the culture and climate middle leaders create, the more likely all the staff are to go the extra mile. This concept is known as ‘discretionary effort’. It is commonly described as the input from individuals over and above that which they need to contribute in order to keep their jobs. Critical in this context, however, is that the effort individuals make is directed productively. Sometimes, well-meaning and hard-working colleagues, regrettably, do not have the impact that their efforts deserve because they are too often focused on doing the wrong things. In a classroom context, it’s all very well having fantastically enjoyable lessons but not if what the pupils are learning doesn’t relate to the curriculum they are meant to be following or the assessments they will have to take.

Delivering through others

One of the biggest temptations for leaders in any role, is to do everything themselves. Very often, middle leaders will be able to carry out a particular task to a higher standard and more quickly than the average member of their team. They may also just relish the opportunity to just show someone how to do something. So for strong delivery through others, it is critical that leaders are in the right mode. As Steve Radcliffe suggests in ‘Leadership: plain and simple’ their first thought should not be ‘what shall I do?’ but ‘who do I want to engage and what is the request I want to make of them?’ This is a shift in mindset and one that some leaders don’t always make easily. Encouraging leaders to pause for a while and ask themselves these questions can be helpful:

- How strong is their tendency to just do a job for themselves?

- Is making the request of others their first or second thought?

- Who are the people they make requests of?

- Who are the people they don’t?

Empowering middle leaders themselves

Of course, these principles don’t just apply to how middle leaders develop the mindset that brings out the best in their teams. In the case-study below, a Teaching Leaders Alumnus who is Deputy Head of a secondary school in Eastbourne outlines how the school’s senior team have applied exactly the same approach with their middle leaders themselves.