“The limits of my language are the limits of my world,” said the great 20th century philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein. He adds, “Language is much more than a communication medium, it is a shaper of reality. Teachers, who are figures of authority and tone-setters, name situations and through the choice of their diction and syntax will create limitations and affordances. Keeping language mindful, open to possibilities, inclusive and positive is vital. The challenge is to remain metacognitively conscious of the power of language at all times so that the reality we shape is what we want it to be. When we stop thinking, the language we produce can be sloppy, deterministic and prejudiced.” Wittgenstein’s thought-provoking words made me begin to think about my own use of language.

Just a few years ago, I was co-teaching in a middle school language arts classroom. The students in our classroom were all certified in special education with a variety of disabilities and therefore receiving direct instruction to remediate their deficits. The pre-prescribed literacy program that we were to teach from was entirely scripted. The program told students when to ‘listen’, ‘look’, and even ‘think’. Students would sit in class, day after day, knowing exactly what was coming next by simply looking at the next page in their workbook, which repeated the same sequence of instructional steps over and over with different content. Students would follow along (not all of them) and respond like robots. Something didn’t feel right. I wondered if I could change the way vocabulary words were traditionally introduced and practiced? I wondered if I could change rote responses by asking open-ended questions and creating an opportunity for students to form new ideas to enhance their learning according to their own abilities? I quickly realised that it wasn’t a matter of swapping one word or prompt for another rather one approach for another. The changes needed to be made were really a shift in thinking.

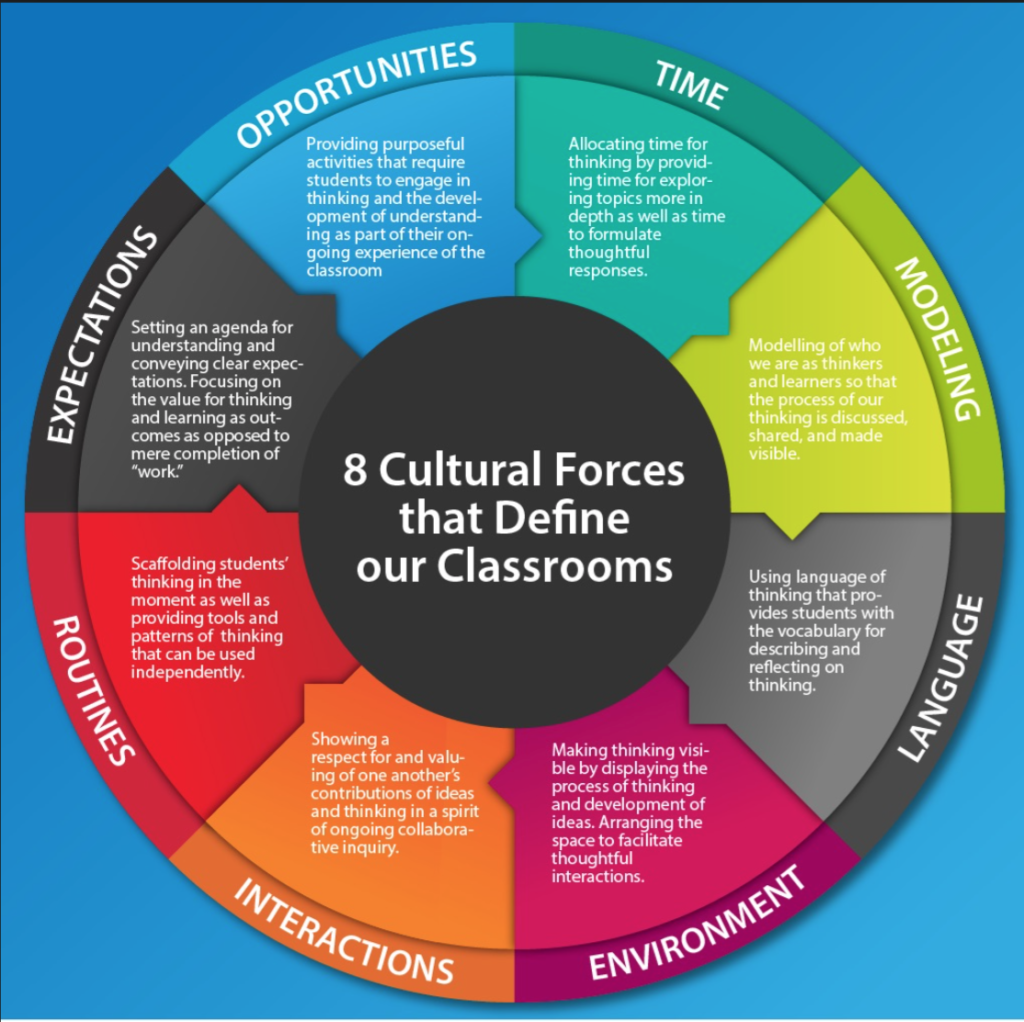

Fortunately for my students, something better came our way – a book called Creating a Culture of Thinking. A Culture of Thinking, defined by Harvard University researcher Dr. Ron Ritchhart, is “a place where a group’s collective thinking as well as each individual’s thinking is valued, visible, and actively promoted as part of the regular day-to-day experience.” Dr. Ritchhart believes that building a ‘thinking culture’ within our schools is the key to better learning. He discovered eight cultural forces that can shape a culture of thinking and contribute to powerful learning and deeper understanding. While all eight cultural forces are always present and working in tandem, the cultural force of Language stood out for me as a place to zoom in on initially, not only to create a culture of thinking but to support and improve the language skills of students.

I got my hands on a resource related to the Cultures of Thinking project titled, 7 Types of Language to Incorporate in Your Classroom. I became excited about the many possibilities to harness language. Just as we prepare for the content and learning opportunities we offer, we can also plan for the specific language moves, questions and phrases that will best promote thinking and understanding. I began to focus on the things I said. I would plan and record questions to press for thinking until they became a habit and felt natural to ask. I would display specific language stems and use the 7 Types of Language to Incorporate in Your Classroom document to prime my language for each class. I learned that our words can shift students’ perceptions of themselves and of their learning, and alter an entire classroom culture. Further, words and phrases hold considerable power over classroom conversations, thus over students’ literate and intellectual development. I quickly began to notice the subtle yet powerful effects of my language. Here’s what happened as I directed myself to the 7 types of language.

The Language of Community

We began using the pronouns ‘we’, ‘our’, and ‘us’. When we use those pronouns, we align with our belief that learning is a social endeavor and that we are in the learning experience together. A key language move on my part was swapping, “I would like you to…” with, “We might consider...” I began to notice students moving from passive recipient learners to active participatory learners who were in control of their own learning. I would often ask, “Where do we go from here?” hoping students would see themselves as part of a community of learners, rather than being dissociated. “Language works to position people in relation to one another.” (Davies and Harre 1999; Langenhove and Harre 1999).

Language of Initiative

Teachers love strategies. We live and breathe strategies, everything from brushing our teeth to writing an essay. We often teach our students strategies often, and that’s not necessarily a bad idea. I always wondered if students were using the taught strategies once they left my presence. I always dreamed of following my students to another class and observing them putting a taught strategy into play in another context, placing them in the driver’s seat. It still felt like I was directing though. I still caught myself offering, “Next you need to...” or “Remember we learned…”. I later learned that knowing and implementing a taught strategy is still different than acting strategically. Learning to act strategically invites and shapes behaviour and enhances agency. I began to elicit questions rather than statements to foster this type of language. I would ask: