The measurement of deep learning must be always informed by a wealth of underlying assessment evidence that captures the complete picture of who students are, what they know and whether they are prepared to use that knowledge to advance their lives and others.

(Joanne McEachen, Assessment for Deep Learning, 2017)

There are many aspects of educational assessment today which are failing. These fall into the four broad areas of:

- what is assessed (focus);

- how it is assessed (methods);

- the impact of the assessment process (consequences); and

- the uses made of the assessment (validity).

Of course there is also a fifth challenge: The degree to which The risk is that schools create students dependent on direct instruction, cramming, drilling and coaching, reliant on expert instruction by teachers who are expected to guide learners through a carefully prescribed body of knowledge, assessed in predictable ways.

An assessment focus that is too shallow and too narrow

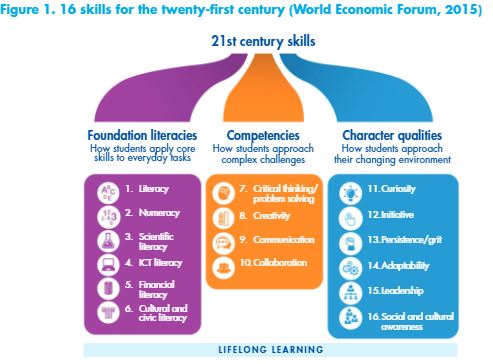

Complex, higher order skills are rarely assessed in ways that recognise the subtleties involved. Many dispositions or capabilities known to be important in life are not assessed at all.

Whatever we might want to measure can be reliably assessed.

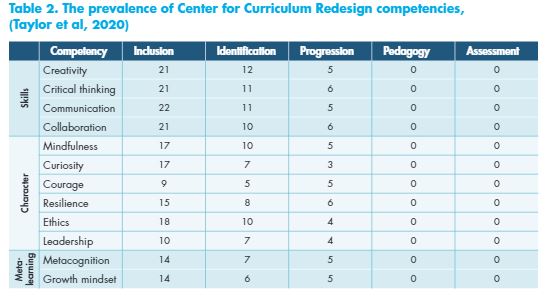

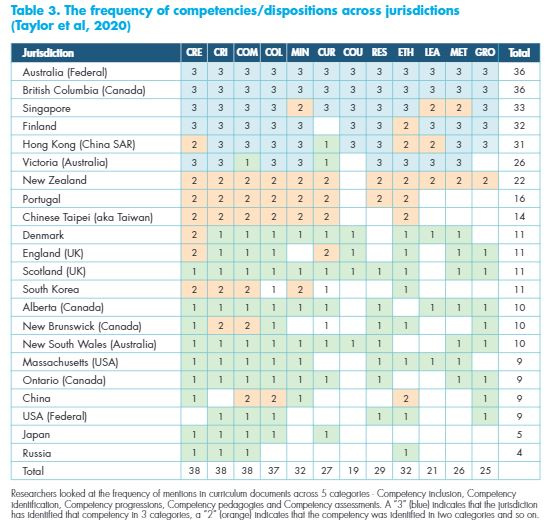

In a recent review (2020) Sandra Milligan and colleagues cut across all of these categories elegantly when they suggested that without a focus on mastery of generic capabilities and assessment.

Currently, the knowledge that is typically assessed is from a narrow range of subjects, rarely explored in depth and almost never interdisciplinary. Practical knowledge and skill is not much assessed in general education, and individuals rather than teams remain the focus. Complex, higher order skills are rarely assessed in ways that recognise the subtleties involved (Darling Hammond, 2017). Many dispositions or capabilities known to be important in life and teaching practices tend to privilege memorisation, essay writing, individual mastery of set content and solving of problems with formulaic solutions are not assessed at all.

Assessments frequently require recall of content but rarely demand the kind of deep thinking, problem solving or application needed in the real world.

Rethinking assessment in education: The case for change

- Traditional areas, literacy, maths and science continue to require considerable content to be tested, while newer areas such as citizenship, engineering, sustainable development and ethical understanding are only briefly explored.

- Except in a very few countries (Finland and Singapore are examples) there is little or no interdisciplinary assessment.

- Practical knowledge and skill is rarely assessed even in those subjects where it once used to be a central component, such as science.

- Students’ capabilities in planning and undertaking extended investigations are rarely assessed.

- Although the ability to collaborate with others is widely valued in the workplace it is only acknowledged at school on the sports field or in music and drama performances.

- While dispositions or capabilities are becoming more visible in curricula they are rarely assessed; at a global level PISA’s innovative domain tests of collaborative problem-solving and creative thinking are exceptions, as is the State of Victoria’s testing of critical and creative thinking.

Assessment methods that are too blunt

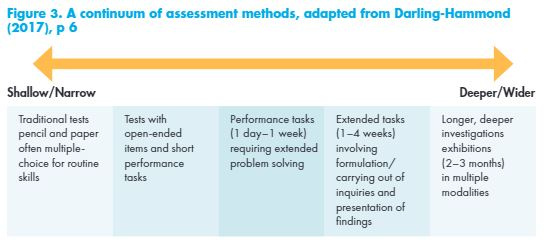

Most tests used in schools still rely on paper and pencil. They examine aspects of knowledge and routine skills. They test students’ ability to remember and write about something, rather than apply or do the thing they have been learning. Concepts and skills are tested in individual subjects and only very rarely across disciplines.

While tests often purport to be criterion based, many countries effectively revert to norm-referencing either because of the scale used (the ATAR in Australia, for example), or the external moderation by an accountability body that keeps levels of achievement very similar year on year (as with GCSE in England). Even where tests are explicitly criterion-based, grades often relate to syllabus content, rather than to more carefully sequenced learning progressions.

Traditional assessment methods typically fail to measure the high level skills, knowledge, attributes and characteristics of self-directed and collaborative learning that are increasingly important for our global economy and fast-changing world.

(Griffin, McGaw and Care, 2012).

A recent High Resolves report (2020) proposes the concept of ‘strings-based assessment’ (High Resolves, 2020) to exemplify the kind of blend or ‘strings’ of immersive, repeated practices and real-world applications that may be useful in evidencing high-order skills in citizenship education. The range of possible assessment methods educational jurisdictions might choose from is actually wide (see Figure 3).

Assessments need not be done in this way, as ‘Measuring progress provides a deliberate counterpoint to the traditional practice of measuring achievement at specific time points’ (Hipkins and Cameron, 2018).

Consequences that are unhelpful

In any assessment system there are intended and unintended consequences, fundamentally, most assessments fail to capture the degree to which students have progressed over time are ready, often to meet the needs of the next educational provider or, frequently ineffectively, of employers. These inflexible encounters with assessment ignore the huge variety of student but it would seem fundamental to assume that an essential principle should be, as the USA’s Gordon Commission on assessment in 2013 noted, that assessment systems should ‘do no harm’.

Sadly, the consequences of the focus and methods of many, especially high-stakes achievement levels, where ‘in any given year of school, the most advanced learners in areas such as Reading and Mathematics can be as much as five or six years ahead of the least advanced learners’

(Masters, 2013), the fact that ‘attainment is only loosely related to age’ (Wiliam, 2007, p 248) and the differing levels of maturity found in any cohort on account of birth dates.

More fundamentally, most assessments fail to capture the degree to which students have progressed over time. Instead they… provide snapshots of achievement at particular points in time, but they do not capture the progression of students’ conceptual understanding over time, which is at the heart of learning. This limitation exists largely because most current modes of assessment lack an underlying theoretical framework of how student understanding in a content domain develops.

(Pellegrino, Chudowsky and Glaser, 2001, p 27–28). Assessments, are well-documented and harmful in a number of ways, including:

- Leading students to conclude that they are failures (Education Policy Institute, 2019);

- Demotivating students to the extent that they may not stay on at school or find employment (Milligan et al, 2020a);

- Making it less likely that students will see themselves as learners and want to continue learning throughout their lives (Tuckett and Field, 2016)

- Causing negative impact on young people’s wellbeing (Howard, 2020);

- Exacerbating inequity (Au, 2016);

- Reducing performance through anxiety, especially for students of lower ability (von der Embse et al, 2018);

- Increasing irrelevance to employers (Harvard Business Review, 2015);5

- Distracting from the huge importance of assessment for learning and assessment as learning (Birenbaum et al, 2015);

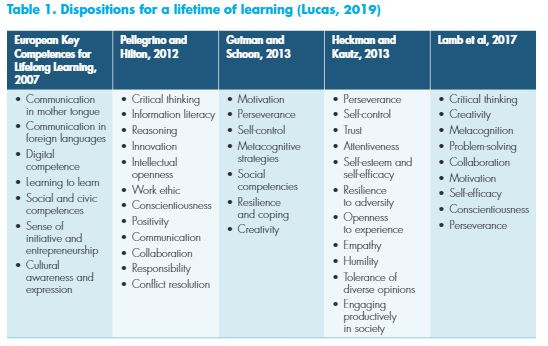

- Misunderstanding and undervaluing wider skills and dispositions by not measuring them (Heckman and Kautz, 2013), and perpetuating the myth that soft skills are easy to acquire and of less value than so-called hard skills such as core literacies;

- Inviting a lack of trust in teacher judgement in some jurisdictions (Harlen, 2005; Coe et al, 2020) Which, in an unhelpfully reinforcing loop, can lead to lower levels of teacher assessment ‘literacy’.

In The Testing Charade (2015), Koretz reminds us of the danger of Campbell’s law, that the more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor… When test scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.

The National Academy of Education (2021) points out that, to avoid unintended and sometimes unfair consequences, we need to communicate clearly (and often) the intended purposes and uses of particular assessments as well as any relevant context.

Dubious validity for many users

Assessment serves many purposes, including the following:

- It certifies, selects and credentials students for universities and colleges.

- It is a sifting mechanism for employers.

- It gives teachers information on the progress of their students.

- It gives students actionable feedback on their progress and suggests potential next steps.

Across the world, however, there is a crisis of validity, with growing dissatisfaction from each of the main users.

Universities and colleges – Universities and colleges find the grades or scores they are provided with too crude to be helpful, so that many are creating consortia to work with schools to provide more rounded information. The Mastery Transcript Consortium,6 the New York Performance Standards Consortium7 and the Comprehensive Learner Record,8 in the USA, and New Metrics for Success, in Australia,9 are indicators of a growing unease with the status quo.

Employers – Employers are frustrated that the current crop of academic and vocational qualifications leave them under-informed about potential employees (Education Council, 2020; Confederation of Business Industry (CBI), 2019). Many employers are now qualification-blind in their recruitment. In England, Rethinking Assessment has identified many examples of, predominantly, larger organisations that operate in this way, including Apple, Bank of America, BBC, the Civil Service, Clifford Chance, Google, The Guardian, Hilton, Microsoft, Penguin Random House, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) and Starbucks.

Many employers now develop their own approaches to assessing potential employees. Often these are ‘strength based’ aptitude tests, looking to see what capabilities and values candidates have to better enable them to work productively with others, seeking to establish a more balanced scorecard than mere exam grades.

When passing tests is high stakes, teachers adopt a teaching style which emphasises transmission teaching of knowledge, thereby favouring those students who prefer to learn in this way and disadvantaging and lowering the self-esteem of those who prefer more active and creative learning experiences. (Harlen and Deakin Crick, 2002)

Institute of Student Employers in England, puts it,

Most employers don’t worry if a candidate knows a little bit less about theories of population migration or the nineteenth century novel. But they will care a lot about candidates’ ability to learn, to think on their feet, to be resilient in the face of knock backs, and so on.

The old narrative of working hard and getting good grades at school

Wherever you are in the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a dramatic interruption of normal assessment activity. PISA’s 2021 tests are currently rescheduled until 2022. Across the world, school examinations for 18-year olds or 19-year-olds have been cancelled, postponed or simplified.12 In many cases these changes have required students to rely on teacher-assessed grades. While this can be seen as a positive development (inviting innovation in methods), in practice it has caused additional stress among teachers who may not yet be assessment literate enough to undertake university and securing a well-paid job is increasingly fractured. Employers are becoming aware that, ‘when it comes to predicting job performance, aptitude tests are twice as predictive as job interviews, three times as predictive as job experience, and four times as predictive as education level’.

Teachers – Teachers have had rising degrees of dissatisfaction with the status quo since the millennium. They are concerned variously about the way that tests privilege certain subjects over others, especially ‘academic’ over practical, and how an emphasis on memorisation can lead to shallower and less enjoyable learning, especially at upper secondary level. This was evident in England two decades ago. such testing without an appropriate infrastructure of moderation and training, along with equitable appeals processes.

Students – Students are increasingly unsettled. In one part of their world they have moved from an era of television programs to be watched at set times, to unlimited on demand consumption of You-Tube, TikTok and streaming services; from books which needed to be learned, to an Internet which can be searched. Not so their examinations, which mostly require pencil and paper completion on a set date and considerable feats of memory.

When it comes to high-stakes assessment, there is widespread and ongoing stress among students, as this blog13 on the website of Ofqual (The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation) in England highlights. In The Testing Charade, Daniel Koretz quotes an alarming letter from New York principals to parents.

We know that many children cried during or after testing, and others vomited or lost control of their bowels or bladders. Others simply gave up. One teacher reported that a student kept banging his head on the desk …

(Koretz, 2017)

Educational jurisdictions

An educational jurisdiction’s performance is also judged through international assessments. Assessments are used as a means by which society rates, often in very limited ways, the performance of its schools. Using tests such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), the success of individual jurisdictions can be compared internationally. These have a powerful impact on both what is tested and how it is evidenced, but that is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Can dispositions be measured?

In the last few decades we have made real progress in understanding how best to evidence dispositions more generally (Soland et al, 2013; Darling-Hammond, 2017; Siarova et al, 2017; Care et al, 2018). In some cases real progress is being made in developing useful standard measures of specific aspects of some key dispositions, for example of ‘grit’ (Duckworth and Quinn, 2009).

Interestingly, it is through tests like PISA that we have been able to make significant breakthroughs in our understanding of how two key dispositions/competencies, collaborative problem solving14 and creative thinking15, can be assessed in an online test. (I have been involved in helping to shape the second of these two tests.)

We have been assisted in this process by advances in assessment technology. For example, evidence-centred design, a way of creating assessments that better demonstrate how test-takers’ inferences are made and their reasoning is developed as they approach assessment tasks, is a promising approach.

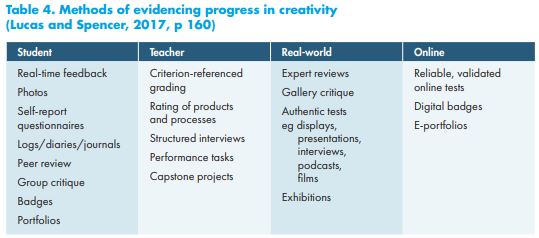

In my own work in the UK and in Australia, working with schools and school systems and drawing on a wider OECD study (Vincent-Lancrin, et al, 2019) with which I was involved exploring the assessment of creativity, I have found that a clear understanding of what creativity is, along with an understanding of learning progression, is a necessary starting point.

Then, provided a range of different perspectives are acknowledged, it is possible to provide students and teachers with robust evidence of progress over time (see Table 4).

Importantly, we need multimodal assessment to gain an accurate picture, using perspectives from at least three columns in Table 4.

However, we have a way to go yet. As Daniel Willingham reminded us in 2013, in his blog, we’re far from agreed-upon measures. Just how big a problem is that? It depends on what you want to do. If you want to do science, it’s not a problem at all. It’s the normal situation.16

In 2016 the journal Applied Measurement in Education compiled a special issue focusing on the assessment of so-called 21st century skills.17 It focused on four types of dispositions: collaborative problem solving; complex problem solving; digital and information literacy; and creativity, to which I contributed our research at the University of Winchester, (Lucas, 2016). In the spirit of scientific enquiry, the issue focused on both what we do know and what we do not yet fully understand. It offered some promising approaches, some of which are already being used by PISA.

Just as these days few contest the notion of the learning sciences as a valid lens to explore teaching, so we need a similar shift in building the science of assessment. I’ll say more about this in the following articles.

This article was first published by the Centre for Strategic Education, Melbourne, Australia

Professor Bill Lucas is Director of The Centre for Real-World Learning

Curator: Creativity Exchange and Co-Founder: Rethinking Assessment

twitter address @LucasLearn

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month