In 1979, when I received my first school computer, there was a lot of education software – that is, there were more titles than we could use and we had to choose which activities we wanted. As the computer studies teacher, I don’t recall paying for software. Certainly, much of the software was begged and borrowed, and quite a lot I wrote for myself and passed that on to others. The system became more organised under the a number of government initiatives including my favourites – TVEI ‘Toolbox’ and the MESU ‘blue file’ of special needs software. The mid-1980s saw the emergence of commercial software houses aimed solely at the education market and issues of copyright and licensing became in important. FAST– the Federation Against Software Theft – came about. The source of educational software moved from being ‘free’, home-grown and teacher-produced to being paid-for, professional and commercial. Nowadays the development of good educational software requires investment of time and resources and has become the business of a number of commercial software houses.

But does it need to be like that? Can we serve our pupils well enough by using non-commercial and free-to-copy software?

There is a growing recognition that ‘open source’ software may be the future, but it is interesting to consider why government organisations, local education authorities and schools have been reluctant to take advantage of the opportunities. First there is the fear-of-the-unknown factor. Whether they are at the LEA level or within a school, many decision makers are reluctant to take risks (and rightly so, as they have the future of our children at stake). Without proven successful practice in their context, many will not proceed.

Small beginnings

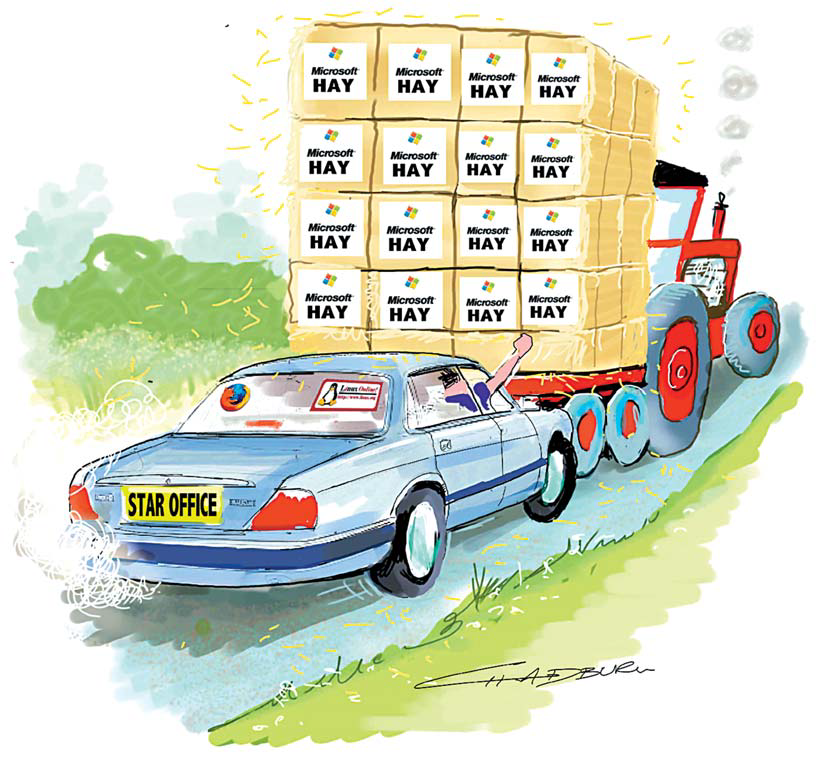

If the open source movement is to become dominant, it must establish and celebrate good practice and grow from small beginnings. It is not likely that a national or local government initiative to adopt a wholesale policy for open source software will occur So why isn’t there a multitude of small initiatives by ICT coordinators saying, “We can save

money by using open source and use those savings to purchase other resources”? Well, Microsoft software is costly, but a computer running Windows and with Office and Internet Explorer installed is ready-to-go. Purchasing a computer without an operating system and generic software needs the intervention of a technician and the time-demanding installation of software. The employment of that technician is not cost-free. Also, the time it takes to install and maintain software has an impact upon the attention that can be given to individual pupils or staff support.

Perhaps the judgement being made is that it is easier and less expensive to buy into the Microsoft solution than to invest the technical support into having an open-source solution. There may be not enough skills in schools to support the widespread implementation of opensource solutions. I am involved in teacher training, and the training of ICT teachers in particular. We do not have any training schools where open source software is in use and therefore we cannot devote significant time in requiring would-be teachers to be open-source competent. Our training is limited to some short presentations (by the trainees) on Linux, PHP, Apache, Moodle and MySQL. This is not significant enough to enable new teachers to have the confidence to say that open-source is a viable alternative to the traditional solutions.

Licensing

There is some misconception about the licensing principles associated with freeware, careware and shareware. The GPL (General Purpose Licence) should make decision makers more confident that they are not entering a spiral of growing costs associated with the licensing of the latest version of commercial software. The licence has two functions. The first is to assure the recipient of the software is free to copy and distribute the software (with appropriate requirement to distribute the licence with the software): ‘The licences for most software are designed to

take away your freedom to share and change it. By contrast, the GNU General Public License is intended to guarantee your freedom to share and change free software - to make sure the software is free for all its users.’