The fourth floor of the stately Longfellow Hall at the Harvard Graduate School of Education is home to Project Zero, one of the longest-running research centres at Harvard University and one of the most impactful in the field of education. Visitors entering its lobby are greeted with eye-catching exhibits of Project Zero’s history, past publications and displays of its current research projects. Works of art and exhibitions of student work line the hallways. Quotes from former and current researchers dot the spaces between doorways. Offices and meeting rooms bustle with dozens of researchers analysing data, discussing findings, meeting with collaborators and writing up results. For five decades, the work of Project Zero’s researchers has illuminated the nature of a variety of human potentials, such as the nature of creativity, intelligence, thinking, and learning. Today their research is thriving, continuing to shape policy, theory and pedagogical practice around the world.

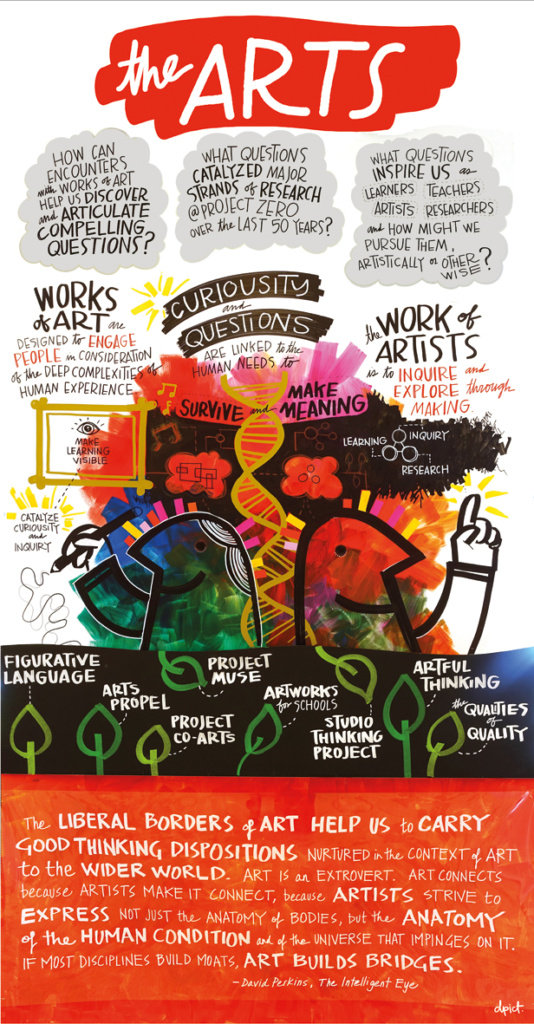

Founded in 1967 by Harvard philosopher Nelson Goodman, Project Zero’s initial aim was to explore and understand the nature of artistic development. Its name originates from Goodman’s view at the time that ‘The state of general, communicable knowledge about arts education is zero. So we are Project Zero.’ That year he gathered together an interdisciplinary group of academics, including David Perkins and Howard Gardner who were completing their doctoral studies at MIT and Harvard, respectively. The group’s early studies led to reports that outlined initial findings on the state of arts education and suggested directions for future research. When Goodman retired in 1972, Perkins and Gardner took the reigns of Project Zero, serving as its co-Directors for the next 28 years

Under their leadership, the centre’s research grew to explore a greater variety of human potentials beyond artistic development. Each new Project Zero Director—Steve Seidel in 2000 and Shari Tishman in 2008—oversaw an expansion of research that built upon previous insights and was fueled by a surging interest in education. Today, Project Zero is home to over sixty researchers working on twenty-five projects and research sites in nineteen countries. These projects range in size and foci – from understanding the nature of playful learning with educators in Denmark and South Africa, to examining the role of the artists in civic life in Australia, to studying how students develop cross-cultural perspective-taking in online learning environments. Each project continues to explore on the nature of human potentials and how they develop in different contemporary contexts.

The articles included in this special issue provide a window into the current and past work of researchers at Project Zero. They frame areas of study and offer tools that were often developed from close collaborations with teachers. To a reader unfamiliar with Project Zero’s work, these articles may seem unrelated given the range of topics. However, below the surface, there are foundational connections. Fifty years of investigations have built the following cornerstone perspectives that bind Project Zero’s past and current work together.

Intelligence as learnable and multiple: For almost a century, intelligence was seen as fixed, general and only measured by standardised linguistic and logical tests. Early Project Zero research revealed that intelligence is a learned ability to find and solve problems and to create products of value in a culture. Each person has a robust set of human intelligences that are developed and expressed within and across cultural contexts. Publications such as Smart Schools1 and Frames of Mind,2 the latter articulating the theory of multiple intelligences, contributed to the conceptual foundations for classroom practices of differentiated instruction, authentic assessment and project-based learning.

Creativity as socio-cultural and cognitive: Project Zero researchers extended their work on intelligence by rejecting long-standing traditions of evaluating single or trait-based conceptions of and tests for creativity. Their investigations exposed the myth of a single variety of creativity. Rather, creativity exists at the intersection of individuals, the domain knowledge and the field of practice. A student in any domain can develop the capacity to solve problems, craft products or define new questions in novel ways that may ultimately come to be accepted in a classroom or larger social setting. In this way, creativity isn’t just the work of a genius, it is the work of anyone and everyone. It is a distributed and participatory process, involving many actors in a given context. Publications such as The Mind’s Best Work,3 Creating Minds4 and Participatory Creativity5 illustrate the mental and collective properties of creativity.