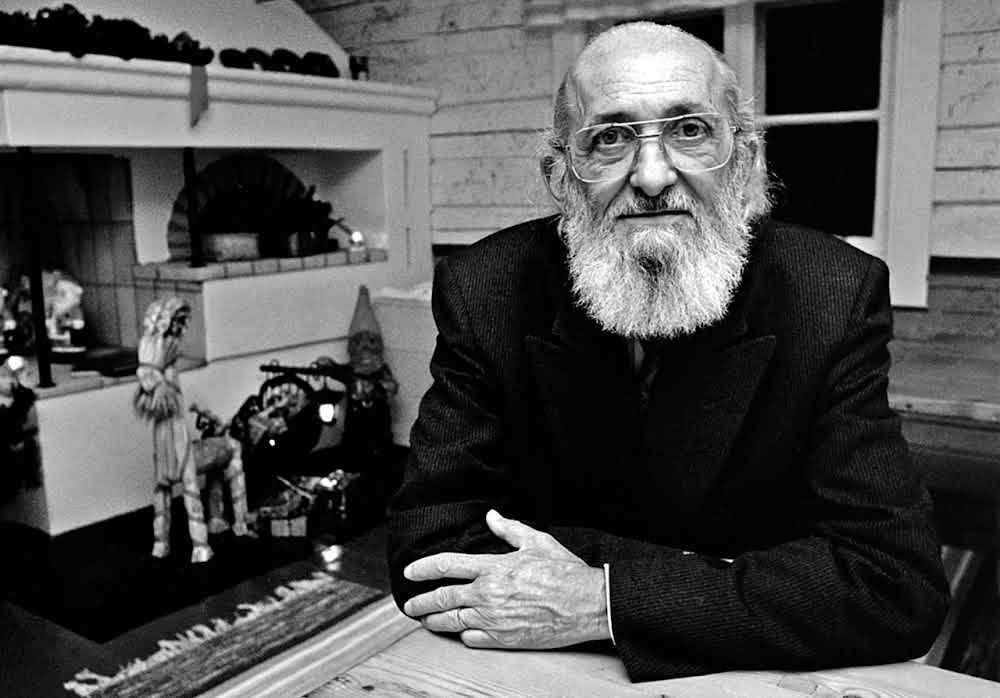

Paulo Freire was an activist, philosopher and educator born in Brazil in 1921. His radical ideas on social reform have had a profound influence in the fields of education and community development around the world. The philosophical and political principles outlined in his books set forth the basis of ‘Liberation Pedagogy’ – education that could grant the oppressed masses a means by which they could understand their own social circumstances and work actively to change society for the better.

The most notable of his works was entitled ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’. In this text, you can find many of the ‘avant-garde’ ideas of progressive educationalists that are now coming back into fashion, such as the centrality of relationships between teachers and learners, the importance of active learning styles like problem-based learning, and dialogic teaching to instil critical thinking skills.

Freire’s experiences of growing up in poverty during the Great Depression greatly influenced his concerns for the poor, as well as the way in which he viewed education. As a Marxist and a humanist, Freire viewed society through a lens of class struggle. Specifically, he examined the relationship between oppressed and oppressors. The key problem for a nationwide liberation movement, as Freire saw it, was that through years of social injustice of living under an oppressive hegemony, the poor had inevitably ended up internalising their oppression; for a poor man to become a realised man, it meant to become like the oppressor.

He understood that a poor person may strive for the power and freedom of a rich person without ever considering that the rich were losing their own humanity through the oppression of the poor. If the peasants were yearning for agrarian reform, they did so not for the liberation of the masses, but that they themselves could become landowners and bosses over other workers.

Freire expounded his idea as a peasant becoming promoted to an overseer, who must surely be as tough on his former co-workers as the boss to ensure standards and quotas were satisfied to protect his new elevated status. The poor had grown with a ‘fear of freedom’, where the oppressed mind shied away from the dangers of liberating ideas in preference to their own personal security, which culminated in a culture of silence and a fatalistic acceptance of the status quo.