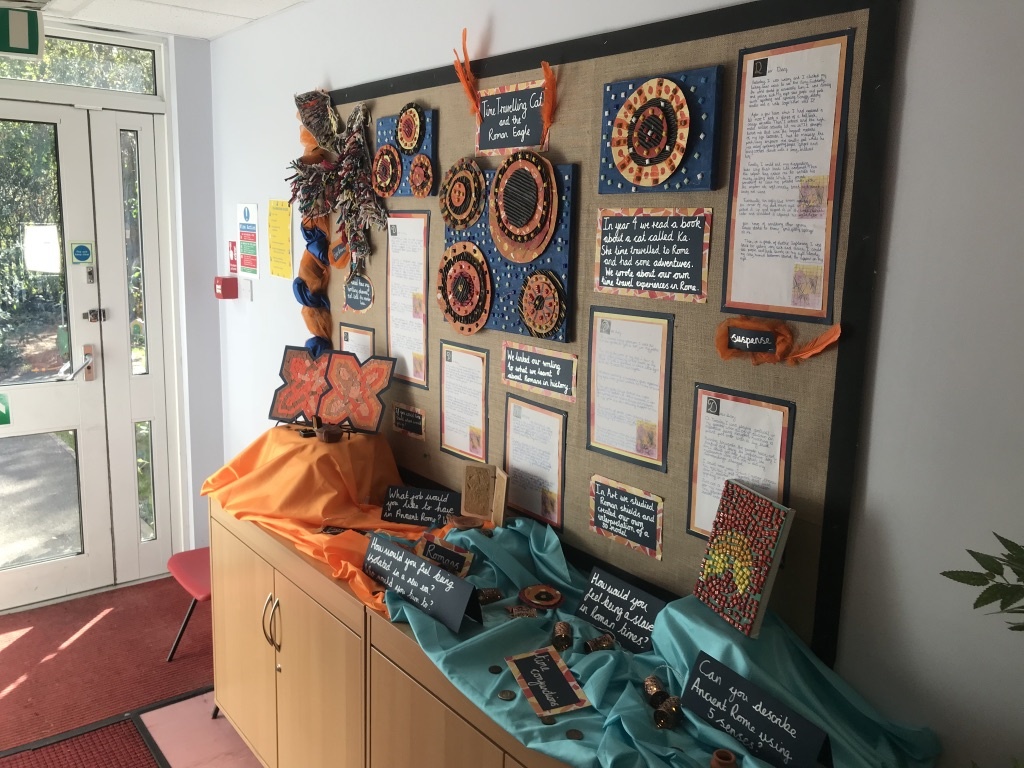

When Ofsted last visited Woodhill Primary School, one of the reasons we were not judged outstanding was the lack of evidence for greater depth learning in French, RE and science books. My abiding memory of the inspection was staff carting barrow loads of books around the building so inspectors could wrestle to justify what constituted greater depth, none of them able to provide clarity or an evidence base for their thinking. It made me question who the experts really were and the role inspection plays in defining what matters. Despite staff and pupils taking great pride in crafting rich, coherent and deep learning journeys across curriculum domains, leading to outcomes above national expectations for greater depth, Ofsted wouldn’t budge. To add insult, the only reference to our curriculum philosophy, connecting subject knowledge to application, critical thinking and deep learning was the line “art is used well to provide a colourful and stimulating environment.” Three years later and still the sentence rips through me like finger nails scraping across a chalk board.

Which brings me to two connected points:

- despite the myth busting, Ofsted still sees its itself as playing the dual role of both evaluating schools AND determining which kind of practice becomes valued or worthy in our classrooms

- because of this, we, as a profession, have to become the storytellers of curriculum and pedagogy, including what we cherish in defining the core purpose of education for our communities, with our communities

Dylan Wiliam recently published an article questioning the role research plays in determining what teachers do in the classroom.1 Classrooms, he argued, are too complicated an environment, bound inexorably by interactions, to be evaluated through a mechanistic evidence base lacking the certainties of scientific law, missing as much of what matters as it attempts to capture. He also points out that the loudest heard education research is produced not by teaching professionals but by academics, those least likely to spend time actually working with children in classrooms.

And therein lies the problem: an academic evidence base seeks mainly to measure what is often easiest to see—the low-hanging fruit—rather than what teachers encounter daily—namely the complexity of relationships, classroom dynamics and other contextual factors.

No better example of this evolved from our obsession with the PISA high performers over the past decade. Policy wonks crowded classrooms of South East Asian schools, proclaiming the virtues of mastery teaching, Singapore maths and whole class instruction. Publishers rushed to pile shelves high with schemes, text books and professional development tools offering a silver bullet to our education challenges. Ministers established advisory groups, effectively creating an echo chamber to justify policy proposals about synthetic phonics, knowledge rich curricula and cognitive science. Meanwhile, the twitterati blogged about working memory, cognitive bandwidth and the principles of Rosenshine, as though teaching and learning were something brand new to the profession.

And here’s the point: while the noise focuses on the most obvious and easiest evidence base in order to provide a narrative for change, what people don’t see are the equally important relational elements of practice which make as much difference to standards and outcomes. Yes, many of the highest performing countries favour a worthy pedagogical model, but critically, they also develop much higher levels of collective efficacy amongst students and professionals to ensure the deepest learning is a collective rather than individual pursuit.