The world of English as an Additional Language (EAL) in education has been slowly shifting to new grounds. Across trusted EAL platforms and training organisations the language for EAL has evolved. EAL has subtly been replaced by Multilingualism.

What has caused this shift and will educational establishments embrace what researchers are telling us about Multilingualism? I will be looking at our own journey at Kensington from EAL to multilingualism, what caused this change and how it has had far reaching implications beyond our expectations.

Introduction

I have been leading on EAL at Kensington Primary in Newham for nine years my work involves supporting and training teachers at my school, our Academy trust, Tapscott Learning Trust, and also schools around London. EAL strategies have always been a solution for those pupils with little or no English: methods with which teachers can support pupils and ensure children with English as an additional language are being catered for in the classroom.

Schools, however, often see children who do not speak English as having something missing: a deficit approach.. Labelling students as EAL can reinforce the importance of English over home languages, to the extent that even exposure to languages other than English (LOTE) is seen as detrimental. Education establishments historically have been trying to ‘fix’ this growing ‘problem’. When children join school from abroad, we assess how proficient they are in English and how quickly we can move them along in their learning. Teachers and other school staff, patiently wait until the child is finally fluent in English and can access the full curriculum at the pace at which it is taught.

The Department for Education (DfE) records a pupil as using EAL if ‘they are exposed to a language at home that is known or believed to be other than English.’1 This means that if a pupil is identified as using EAL when they start school at 3-5 years old, they will continue to be recorded as an EAL user throughout their education and their life. This includes children who have grown up speaking English primarily in the home and whose second language is the weaker language. Sounds simple- however, schools are increasingly taking in pupils from abroad who have little or no English and who may speak two other languages outside of school. Add in the mix of children with no previous education and no formal literacy in their first language (L1) and the picture gets more complicated.

Working in Newham, an East London borough with one of the highest proportion of pupils (75%) that speak languages other than (or in addition to) English at home (NALDIC, 2015). An area where the mobility rate is exceptionally high (20% per year in certain areas). How do we work at this pace with a wide range of languages, educational experiences and cultural differences? How do children access a curriculum that requires them to have the fluency of a native English speaker? And how do we support these children and families who may have limited resources and no understanding of the UK system? Most importantly, how do we emphasise the positives of our multilingual children and families rather than just seeing the challenges?

Curriculum K

These questions, amongst others, led to our school launching Curriculum K. This new curriculum was born after two years of research and studying different models. Prior to this, our curriculum at Kensington was not supporting children from diverse backgrounds, some of whom have limited resources, support and space.

One of the changes our curriculum brought in was health being a core area of the curriculum: children who have regular exercise and can learn how to regulate will be ready for learning. As part of the new curriculum, we also looked for an alternative to Modern Foreign Languges With currently 45 languages in our setting and 97% of children speaking an additional language, adding another language seemed counter-productive. Our solution was to focus on ‘Promoting first languages’.

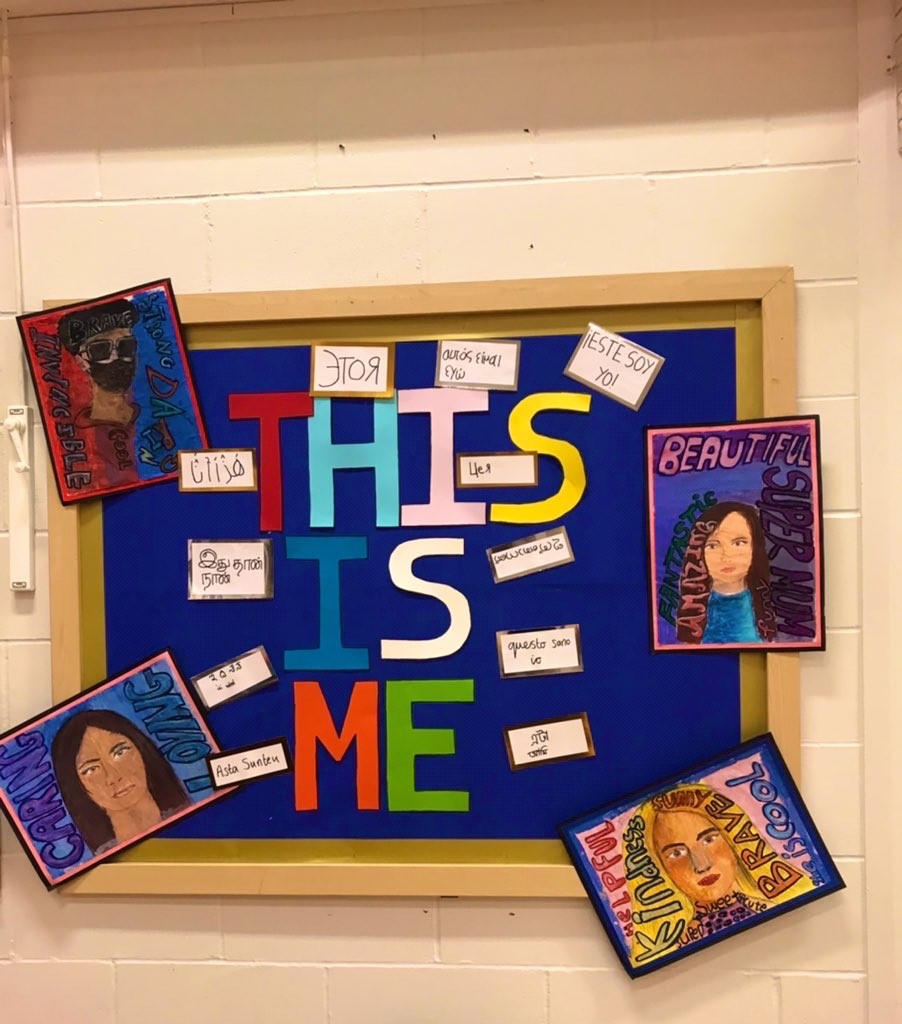

This shift in approach led to a far greater shift in mind-set. Celebrating and promoting first languages was now our focus, which made promoting multilingualism all that more seamless. Our language, therefore, shifted from using EAL to Multilingualism, referring to pupils as ‘multilingual’ gave all languages an equitable status and focused on languages being a valuable resource. As part of this way forward we wanted first languages visible in books and on displays, the use of translanguaging in classes, and after school clubs in first languages to support this approach. The use of translanguaging was transformative in the classroom. This allows multilingual pupils to use their language resources to inform their learning by translating key words or essential information and to discuss topics in their first language. ‘Classroom instruction should encourage students to use their full linguistic repertoire in flexible and strategic ways as a tool for cognitive and academic learning.’6

Linguistic repertoire

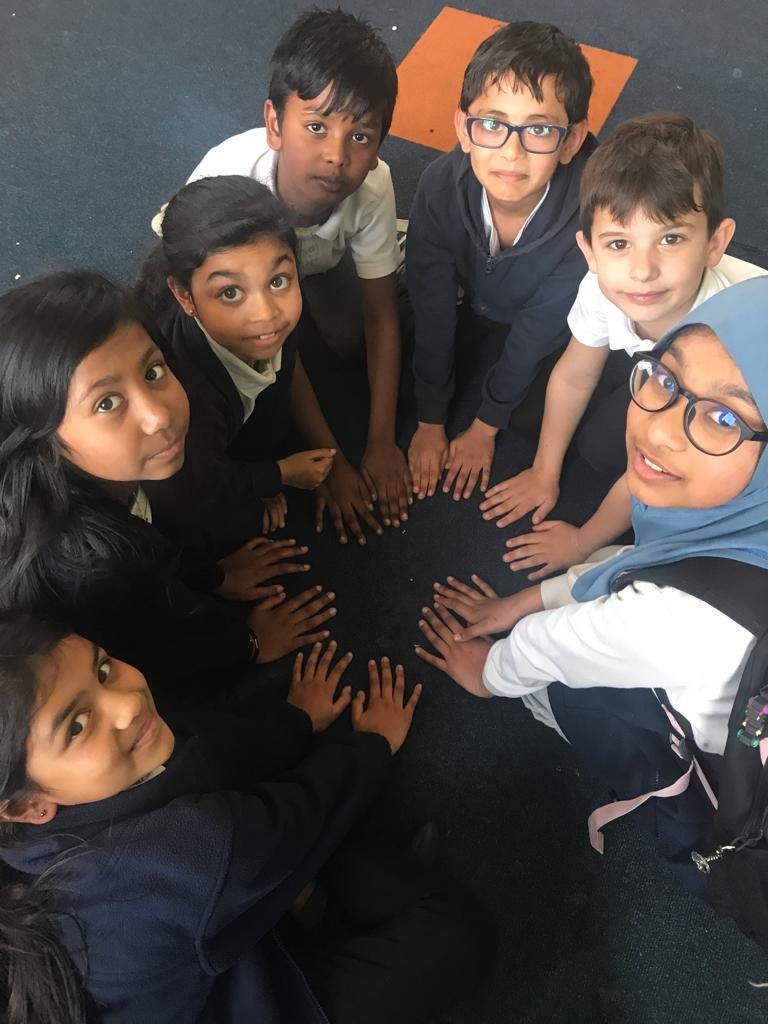

Staff were inspired, Having multilingualism as an approach opened up a whole realm of opportunities in the classroom and focused on the linguistic repertoire these children have, giving us an asset-based approach. Armed with a mind-set that focuses on languages as a resource, staff became empowered. Lessons were drawing upon the linguistic repertoire of the classes and teachers were discovering a new level of engagement with multilingual children. A year 2 class teacher discovered that most of her children spoke three languages. A Year 1 class began collaborating with a Year 5 class to build confidence in their first languages. First languages found its place in the classroom, and it started weaving itself into teaching and learning in the most creative ways.

Whilst training staff on methods of translanguaging and best ways to promote this as a whole school approach, I required more evidence to further support this area. This led me to start contacting some Universities; these children and the linguistic repertoire they have bring strengths with them to education. Research points to certain abilities multilinguals possess: how languages shape the brain and determine a person’s approach to challenging situations.7 A recent study in Cambridge, of just over 800 pupils in England, ‘found a positive relationship between GCSE scores and ‘multilingual identity’: a reference to whether pupils felt a personal connection with other languages through knowledge and use.

Those who self-identified as multilingual typically outperformed their peers not just in subjects such as French and Spanish, but in non-language subjects including maths, geography and science.’’2 The link between multilingual identity and attainment shows that a multilingual mind-set would support children in their learning, regardless of how proficient pupils were in another language. The study suggests that, ‘even young people who see themselves as monolingual possess a ‘repertoire’ of communication. For example, they may use different dialects, pick up words and phrases on holiday, know sign language, or understand other types of ‘language’ such as computer code’ 2.

Linking academic research to EAL provision to school provision

Multilingualism had more to offer than first languages and with a headteacher willing to back this approach and teachers keen to put it into practice, I knew we had something that needed to be explored. On my quest to create links I met two Academics from Metropolitan University. Not only were they willing to share research with myself and teachers at my school, they also wanted to take this a step further by submitting a research grant for our up-coming collaboration; which is titled ‘Promoting multilingualism at school: How researcher and practitioner collaboration can support and inform the educator-student-community triad.’

At a recent lecture by the director of the department of Education at Oxford University, ‘Bridging educational sciences with practice in education’ (26th April 2022, Institute of EducationL) It was stated that there was observational research for multilingual pedagogy but no concrete research.

Schools were not willing to take a risk where the impact was unknown and it is a difficult area to change with schools under significant pressure. Whilst attending a seminar on ‘Growing up bilingual’ I met the director of UCL Multilanguage & Cognition lab and Co-director of Bilingualism matters. His primary research focuses on multilingual acquisition and its effects on cognitive control, memory and metacognitive processing from infancy to older age. In particular his work has shown that multilingualism may be particularly beneficial within disadvantaged society3. We organised a visit to my school and the Professoralong with his doctoral students spent a day at Kensington.

They observed lessons, met SLT, teachers and spoke to multilingual pupils with different levels of English. Their verdict? We had encapsulated the multilingual pedagogy in our school, that it was embedded in what we do and that was evident in all that they saw. Where to next?

An example from Jersey

Whilst there have been a surplus of lectures currently on this growing change to EAL practise and schools have been crying out for help with new arrivals and refugees, one of the Islands in the UK has been carrying out some extremely timely and interesting research. The island of Jersey, home to 62 languages across the Island, and 26% multilingual pupils across their settings from nursery to Year 13, set aside part of their Education reform programme to improve provision for these learners. Academicsarried out a review of their provision and one of the first recommendations was a whole-sector language policy. ‘The vision was to create a fully inclusive language policy that addressed all varieties of language and level of learner, and could drive good practice across the Island.’4 The policy promotes the use of all community languages and states,” All students in Jersey schools should be provided with rich and varied opportunities to engage in language awareness, language development and cultural development.

While English remains the primary language of instruction in Jersey schools, it is the goal that all students will have the opportunity to engage in language acquisition in meaningful and useful ways, especially in the languages spoken in the wider community in Jersey.”5The policy was launched on May 5th 2022, subsequently we received a visit from a primary school on Jersey . With this inclusive language policy in place, they were tasked with visiting various schools to view good practice. The launch in September will require them to have seen different approaches to a multilingual approach and how best to put this into practice in their own unique setting. With the backing of a robust policy and language reflecting the different language needs: MLL for multilingual pupils and the use of EAL for those new to English. Schools in Jersey are championing the way to a multilingual approach in the UK.

With a language policy in Jersey promoting multilingualism, schools in London having various practices around multilingualism with some needing further guidance, and researchers requiring more opportunities for concrete research in this area, the term EAL seems to shrink next to its counterpart ‘Multilingualism’ which provides a far more exciting way forward in the global world today. The task for education settings is to navigate this area and decide whether they will continue upon the tried and tested route of EAL and provide continued robust support for EAL pupils, or to change their approach and mind-set to one that embraces Multilingualism and all the strengths it can bring to their setting.

At Kensington, we are already seeing the impact of taking a positive, asset-based approach to multilingualism. Children’s confidence is growing. We are seeing greater pride in first languages. There is increasing evidence of children translanguaging in lessons and through their books and displays. Our children have always been translating for each other but now there is a new sense of pride in languages. In a year 6 class recently, they were creating bilingual glossaries for Beowulf.

Children who were new to English and multilingual children shone! They were translating words flawlessly, identifying changes in word pattern and highlighting gender words. One child who has been at the school since year 2 shared how he speaks four languages at home, Spanish to one grandparent, Italian to another, Russian to his uncle and Romanian to his parents! Impact has also shown up in the most surprising ways. After-school clubs in first languages have seen children joining each other’s language clubs. Hindi and Tamil speaking children joining Romanian club, Lithuanian and English joining Bengali club and English and Bengali speaking children joining Tamil.

An English speaking parent asked the Tamil club teacher for key words so they could practise at home. There is no hierarchy in languages here, parents are supporting this approach and valuing all first languages. Our hope is to continue on this journey to provide a multilingual mind-set and approach in our school community. By collaborating with academia to ensure multilingualism creates its own unique pathway in education. One in which we can equip our children to use their multilingual superpower in further education and beyond.

Conclusion

To truly champion the way for Multilingualism, schools need to use a whole-school approach. Involving all layers of the school, from leadership to governors, from class teachers to parents and the community. This must include promoting all first languages spoken by the school community and ensuring it is reflected through the displays, website, performances and communication with parents.

We must encourage the linguistic repertoire our pupils have by allowing them to translanguage and work in ways which ensure they can navigate their languages successfully for different tasks. Multilingualism should not just be seen but should be experienced by everyone. Opening up the discussion around home languages with all stakeholders will bring diversity to the forefront and ensure that we are valuing the whole child and all that they bring with them.

Soofia Amin is SLE for Multilingualism and Assistant Head Teacher at Kensington Primary. in Newham London

References

- https://www.bell-foundation.org.uk/eal-programme/guidance/education-policy-learners-who-use-eal-in-england

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/students-who-self-identify-as-multilingual-perform-better-at-gcse

- https://iris.ucl.ac.uk/iris/browse/profile?upi=RFILI07

- https://www.gov.je/News/2022/pages/firstlanaguagepolicy.aspx#:~:text=Sam%20Losh%2C%20the%20new%20language’s,where%20everyone%20feels%20they%20belong.%22

- https://www.crisfieldeducationalconsulting.com/single-post/whole-sector-inclusive-language-policy

- https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Education/P%20Language%20Policy%2020211108.pdf

- https://www.ecis.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Cummins-Chapter-2-in-Pedagogical-Translanguaging-book-MM-2021.pdf

- https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/multilingual-practices/0/steps/22658

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month