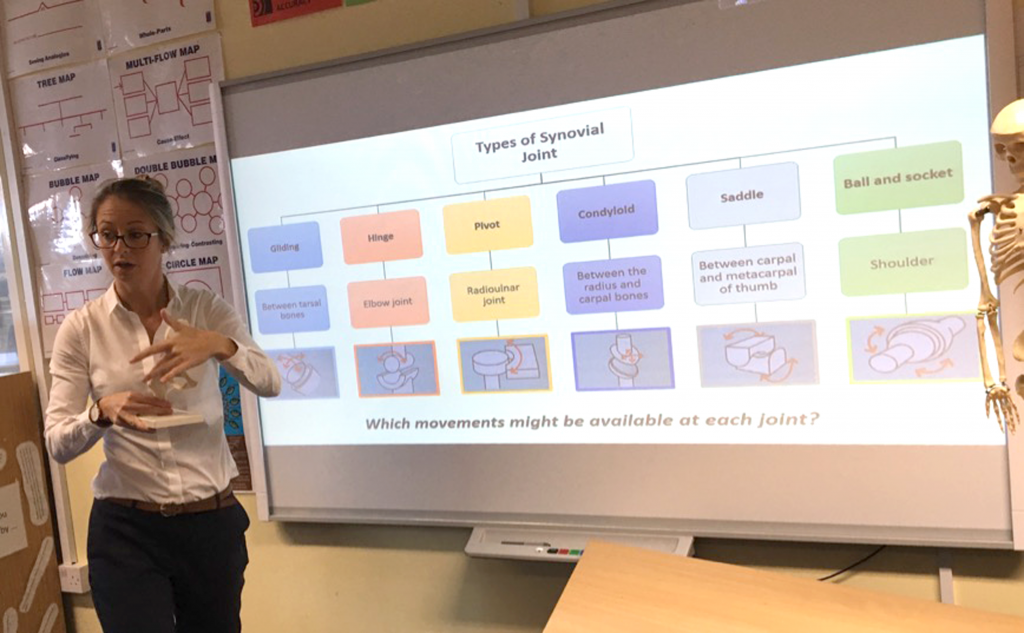

When embarking on a new stage of schooling, each student brings with them a different experience of what learning looks like and feels like, often reinforced by their experiences – sometimes positive and contributing towards the development of a confident and competent learner, but other times negative, which can leave learners feeling overwhelmed, anxious or despondent. Hyerle and Alper state that, ‘Thinking Maps serve as a device for mediating thinking, listening, speaking, reading, writing, problem solving, and acquiring new knowledge’ and for our Trust schools, these visual representations provide a ‘portal’ into the thinking that is taking place in the heads of our students and a language to communicate it.1 The infusion of Hyerle’s Thinking Maps across the whole curriculum has provided our students with a method to sort and present information, providing a rich vocabulary to express and discuss their ideas in relation to the content they are studying and their underlying thinking.

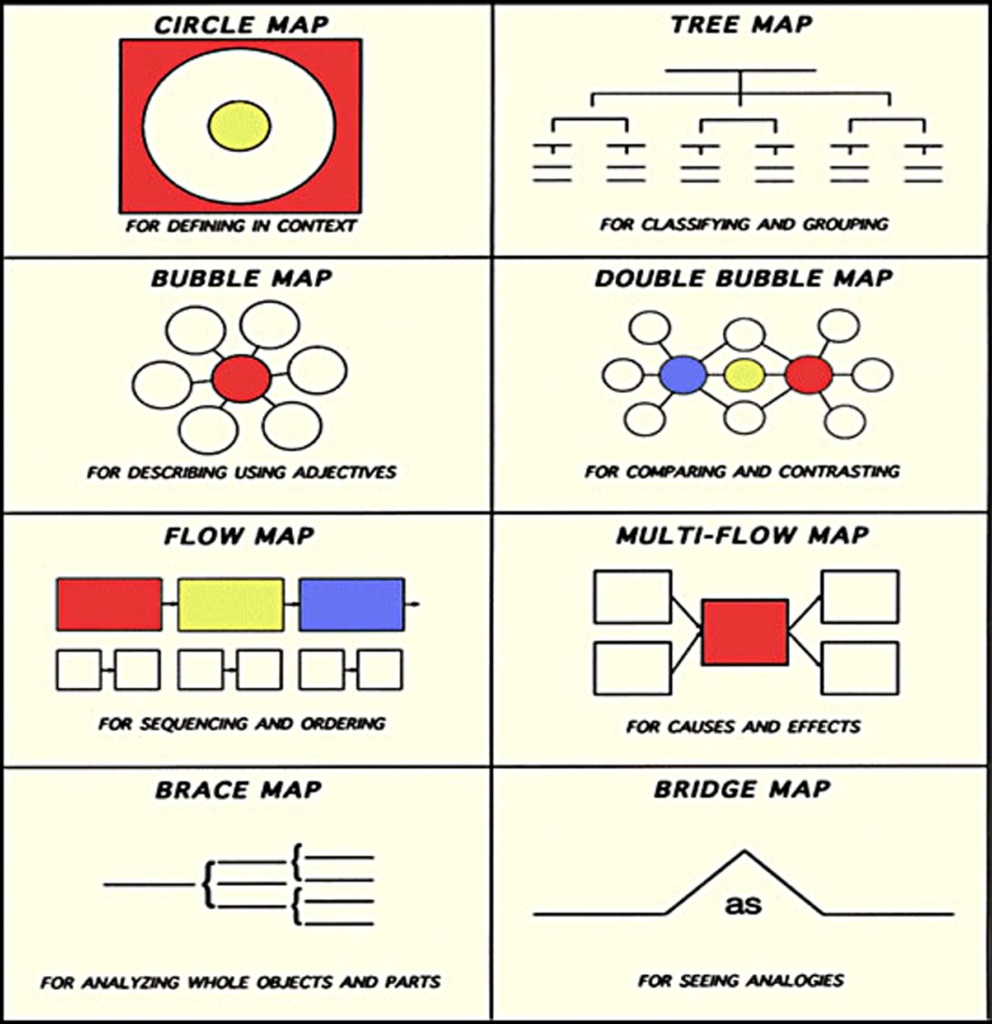

The Thinking Maps as designed by Dr David Hyerle

| Thinking Map | Thinking Process |

| Circle Map | Defining in context |

| Tree Map | Classifying |

| Bubble Map | Describing |

| Double Bubble Map | Comparing and contrasting |

| Flow Map | Sequencing |

| Multi-Flow Map | Causes and effects |

| Brace Map | Identifying whole/part releastionships |

| Bridge Map | Seeing analogies |

Visual structures are nothing new – long have Venn diagrams, spider diagrams and other graphic organisers been in use in education, but within our Trust this has been developed into a shared common language across all subjects and key stages that is improving our students’ confidence and competence in their learning.

The Trust is composed of fourteen schools, ranging from single-sex grammars and mixed high schools to infant schools, all across a quickly expanding geographical area. Our secondary schools have seen real improvements in attainment since joining the Trust: on average the Progress 8 score for 2017 was 0.68, and throughout this time we have been keen to attempt to assess the potential impact of the Thinking Maps as a possible contributor to these improvements in learning outcomes.

Despite the differing contextual demands, for both staff and students, the Maps have provided a strategy for handling the curriculum content in a way that enables students to form meaningful links to previous learning and structure their work in a digestible format. The simple and easy-to-recall visual representations are used often to support the activation of prior knowledge before learning a new concept, during learning episodes and also keenly as after lessons to review, assess or summarise understanding.

In our secondary schools we have found, especially for younger secondary students, the levels of confidence relating to learning new content has increased, as has the quality of students’ metacognition when talking about their learning. By the end of Year 7, students are already more articulate when discussing their thinking – not just in terms of content that they do and don’t understand, but also in how they came to reach their answers, plan their approaches to solving problems and modify their strategies depending on how successful they are.

In order to reap these benefits, all students and staff have been explicitly taught the ‘conventions’ of each Map with some theoretical underpinning, provided with examples of application and then guided to design their own examples to specific content, through a formal induction programme. Cross-Trust training for staff enables a richer professional dialogue, enabling staff to discuss applications into their own varying contexts. The shared language also allows more opportunities for cross-curricular sharing, breaking down barriers between subjects and increasing awareness of the similar types of thinking needed in each subject, e.g. a Flow Map might be used in Maths to solve an equation, while this ‘thinking process’ is also useful in PE to illustrate the stages of throwing a javelin.