We’ve had standardised shipping containers since the 1950’s and it didn’t take long before people started converting them into habitable spaces. However due to their availability, cost (you can pick up a used 40 foot single-journey container for around £4,000 or a 10-journey one, which might have a couple of ‘dings’ in it for less than half that) and eco-friendly credentials, Deadheads (the name given to reclaimed retired containers) are starting to be seen more frequently as offices, restaurants and even learning spaces. There are an estimated 30 million redundant containers worldwide, with many more in the West due to an imbalance of trade between the Far East and Europe. So if you’re from Dundee, you’ll probably be familiar with the 37 shipping containers used to build accommodation for creative start-ups on Dundee Waterfront. Or if you’re from the Shalesmoor district of Sheffield, you’ll probably be aware of Krynkl – a similar development that incorporates a Jöro restaurant due to open later this year and which was designed by Coda architects again using (yes, you’ve guessed it) the humble shipping container. Further west, Bristol hauliers, Bristol & Avon Group followed suit for their headquarters office just off the M49 designed by Mackenzie Wheeler architects and even Central London isn’t immune - Thomasina Miers’ Southbank Wahaca restaurant next to the South Bank Centre is also built out of them.

They’re much more readily used by educational establishments in the developing world (where an added advantage is that they can be fitted out off-site, transported to schools and lowered into position in a couple of days) to the extent that when we put out a call to architects to tell us about projects, it was two from South Africa (see the following case studies) who responded first. But as the world of austerity continues to bite here in the UK, more and more schools are looking at using structures which, unless they’re trundling down the motorway or are atop an ocean-going ship, are more commonly seen surrounded by nettles in the corner of a sports pitch and used to store the cricket nets in. Because whatever Michael Gove said about extravagant architecture when, in 2010, he cancelled Building Schools for the Future, 2 years earlier Lambeth’s BSF programme saw London-based architects, Scabal, knock one-third of the cost of even the most basic sports hall, delivering a new facility for Dunraven School in Streatham built out of shipping containers for £1.5 million. St Bede Primary Academy in Bolton, too, turned to shipping containers to deliver a similar saving off the cost of building additional classrooms, first in 2013 and then adding to these so now 10 classrooms are formed from shipping containers. The ultimate recycling project for a school, they have elected not to clad them to disguise the corrugated metal sides, but instead to keep them painted grey, celebrating their origins and as a clear message to support the school’s core values: learning, caring and growing together

So, whilst he’s perhaps more frequently seen with George Clarke or Kirsty Alsopp on television, designer, entrepreneur (and now television presenter too) Max McMurdo has partnered with Lion Containers to create Reetainer classrooms. Max came to the nation’s consciousness when he appeared on the television programme, Dragons Den, showing them “Ben the Bin”, subsequently persuading Deborah Meaden and Theo Paphitis to invest in his fledgling upcycling business, Reestore. And whilst it’s the link back to the environmental benefits that clearly has as much emotional tie with Max who has built his career turning wheelbarrows and shopping trolleys into seats, Bunsen burners into lights and even a bicycle into a stool, Max has long been a big fan of the use of shipping containers as a building block for the creation of habitable space. He uses one as his own office (that was the first of his projects featured on George Clarke’s Amazing Spaces in case you missed it!), so when his former school, Sandye Place Academy in Bedfordshire saw that and contacted him, he went back to school with two 20’containers and helped them create their very own eco-classroom. “They were doing it [eco studies] in a boring old science lab before” explained Max, before describing how the new classroom space (the “ultimate eco classroom” Max calls is) has old classroom table frames as the banisters to the deck outside, and the table tops (“complete with all the rude words still written on the underside!”) as ceiling insulation inside. It has bicycles connected to dynamos to back up the solar panels on the roof, and harvests rainwater from there too. And, in this instance, its construction was the work, as much, if not more, of the Eco-Warriers club at the school as Max supported them in the design of it rather than taking on that aspect himself. “It’s a wonderful learning concept” continues Max, where students have a real respect for their leaning space as, like the Spanish students (see page 42) they had a personal investment in its creation whilst also learning new skills in its construction. With Reetainer projects, on the other hand, he acts as designer and project manager, with the implementation being handled by Lion as a straightforward ‘turnkey’ solution, and in these instances, a finished classroom space can be completed for less than £20,000. “Eco buildings have traditionally been made from timber, mud and tyres” commented Max “and often lacked that cutting edge contemporary aesthetic”. In Reetainer, as well as the two projects shown below and page 12 , he’s proved that however unlikely it might sound, with an old shipping container, you can certainly do that.

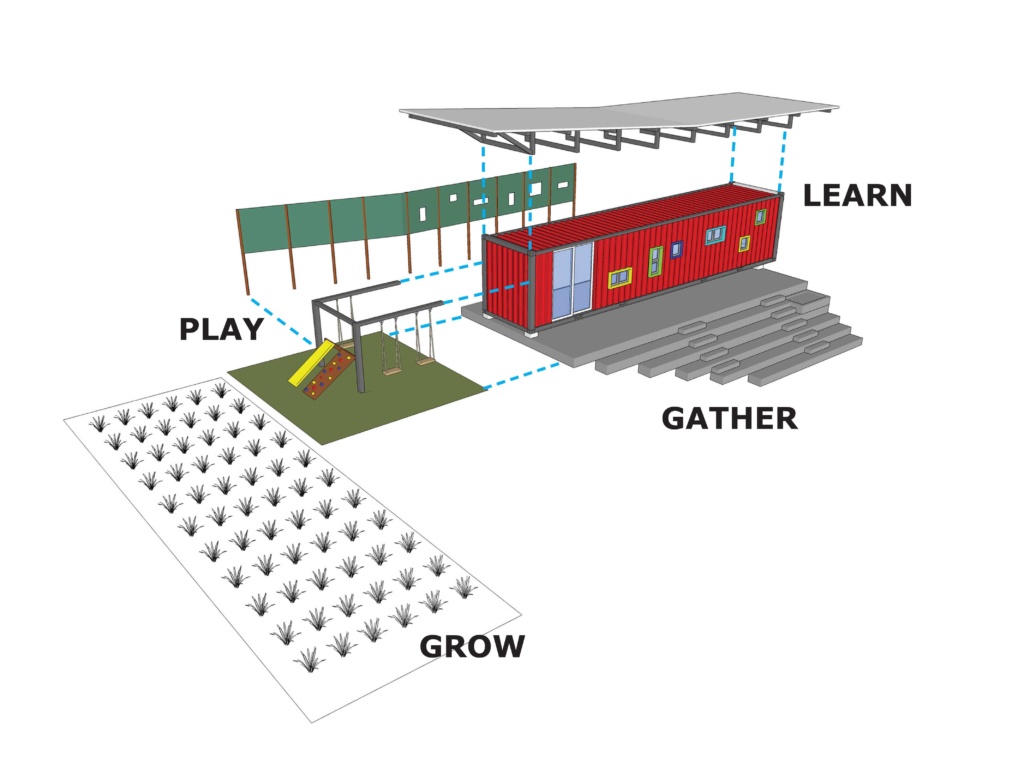

Somewhere to learn, somewhere to gather, somewhere to play and somewhere to grow were the four distinct spaces required at the rural Visserhok Primary School situated in the Durbanville wine valley on the outskirts of Cape Town. The school, which is attended by children of farm workers and underprivileged families living in nearby Du Noon Township was designed by South Africa’s Tsai Design Studio, funded by Woolworths, Safmarine and AfriSam, and won a silver medal at the Loerie Awards in 2013.

Funded by South African charity, MAL Foundation, Architects of Justice designed the SEED library for MC Weiler Primary School in Alexandra, Johannesburg, creating “an exciting and stimulating place to foster the love of learning”. The roof saw an open air reading platform whilst the cantilevered structure supported a swing in this playful use of a shipping container. The SEED library accommodates all of what were considered the basic functions – somewhere to access information, complete homework or read. “It is a working example of an exciting stimulating place” explains AoJ, “that not only houses knowledge, but also, through the use of colour, shape, light, the outdoor, and imaginative & inventive space, gives the user an inspiring experience when accessing it.” By cleverly orientating the two containers perpendicular to each other, they created shading as well as creating visual interest.

And finally …

Noticing it lying, seemingly abandoned beside a runway at Southend Airport, specialist media teacher Jon Baker persuaded the school he worked at to buy the redundant Cessna jet and turn it into a learning space for up to 15 children at a time at Milton Hall Primary School in Westcliff-on- Sea in Essex. The school wanted somewhere for small groups – be they gifted and talented learners needing to be stretched academically, or more vulnerable students who needed somewhere nurturing (the school has higher-than-average EAL and SEN students), and had looked at prefabricated pods. But they felt, as well as potentially taking up valuable space on the school’s sports pitch, they were expensive. The streamlined Cessna Classroom, on the other hand, could be tucked onto a parcel of land that didn’t detract from outdoor play and has, as is unsurprising, been a big hit with the whole school community – especially boys who are no longer reluctant to go out and read. Jon, and one of the school’s caretakers took on the refurbishment of it themselves, keeping costs to an absolute minimum. Whilst it’s relatively new into service, it has already been used for maths extension classes, (giving students just 5 minutes to complete the test and therefore replicating the pressure a pilot would be under), as well as a re-enacted plane crash requiring students to improvise. But its main purpose is as an eco-centre, so there are solar panels with equipment to measure energy used and energy generated as well as rainfall. And whilst they’re not alone – Kingsland Primary School in Stoke-on-Trent have had their Phoenix Aeroplane learning space since 2009 when they converted the fuselage of the 72 ft Short S-360 aircraft – their DIY approach to the plane’s fit-out is an education to us all.