As the current Felipe Segovia Chair of Learning Innovation at Universidad Camilo José Cela in Madrid, Professor Stephen Heppell has long triumphed student voice as one of the most relevant ways to reimagine learning. Because he thinks, too, that learning is best when it’s engagingly enjoyable. So, together with staff at the University, two schools in Madrid together with one in Barcelona (all three schools are part of the SEK group of international schools founded by Filipe Segovia) they put in place a 3-year project in order to design spaces to make better learning. Initially the project, which took place between 2012 and 2015, was planned with the first year spent researching and planning, the second implementing and the third analysing the results, although, as Stephen observed “some ideas took longer to put in place than others” meaning the third year actually included some implementation too. We talked to him about the study.

“Rather than asking our learners for their opinions” Stephen explained, “we first asked them for their research: what had others done, what had seemed to be effective, what were the reasons behind others’ changes and ideas, what is unique about our own learning community, what data can we collect at the outset to inform our reflections?” Because, as Michael Van Ostran, one of the teachers involved commented, they needed to distinguish between “what would be fun and what they would like to do that leads to better learning” What Michael admitted too, was that initially he had been sceptical about letting the students loose, but had been won over (“I learnt my lesson” he admitted, bravely) as the project proceeded. Because at the beginning, one of his students observed: “you know” he said, “I’ve been in seven schools and this was first time anyone thought to ask me how it could be better. But I’ve always known...” Amongst other research, the students drew on the experiences of the students who had been involved with the project at Lampton School completed with Juliette Heppell (which we covered in volume 2.1) as well as looking at, and talking to schools in Denmark, and visits to exhibitions and furniture showrooms.

They gave students deliberately tight budgets to work with, typically around €500, but different for each school enabling the study to also consider what differences existed when different budgets were given. By not giving them seemingly bottomless pits of cash, this forced choices and decisions on the students. “They had to weigh, choose, compare, contrast and evaluate the contributions resulting from every choice they made” Stephen commented, before continuing “This was important; for a generation comfortable with mashing-up solutions and who are beginning to return to make-and-create rather than the buy-and-consume of their parents, the ability to “mash-up” better learning was a direct result of those forced budget choices. This is what we want gave way rapidly to this is what we can make work best.”

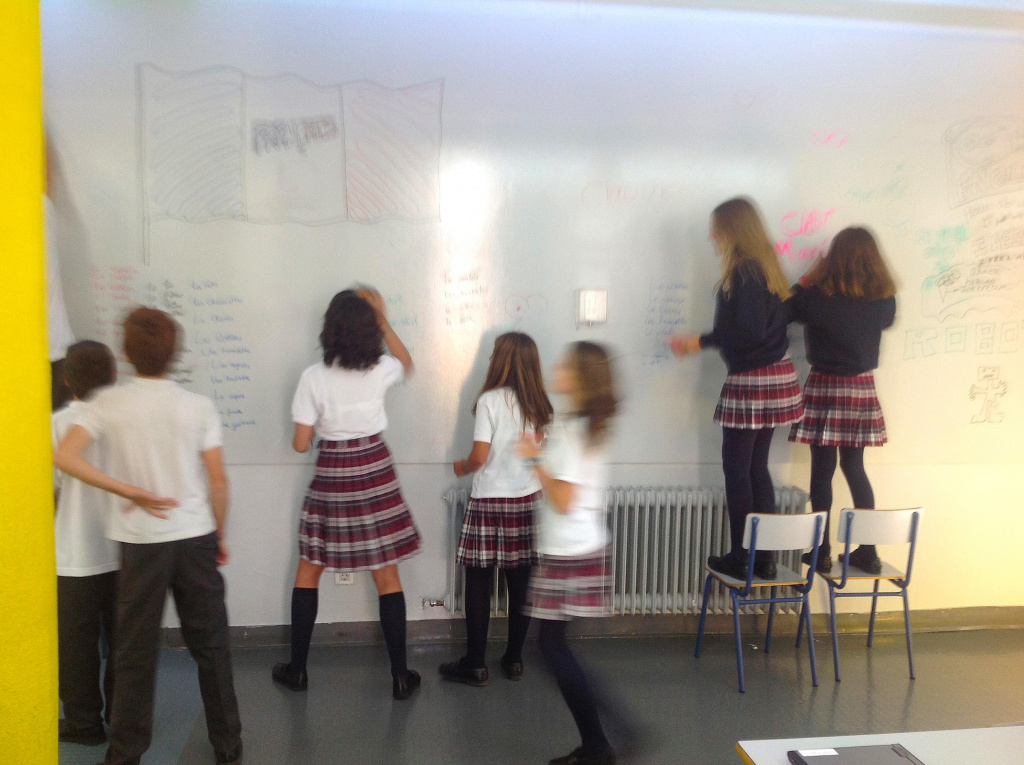

There were some clear themes that came out of all three projects. All included clear zoning of spaces – with different areas created to support different activities. And the function of these, too, were similar – somewhere to work together collaboratively, somewhere to present both to small and large groups, and somewhere for quiet concentration. The characters of these zones differed from each other – the one for quiet concentration typically being furnished with soft upholstered seats – beanbags in the case of Ciudalcampo and a couple of old sofas repurposed from the school flat in the case of Catalunya (who had a budget of nil – but who’s brief was to create a prototype and where this has subsequently been, in part implemented by the school). And whilst Catalunya felt that the collaborative space ought to be made of individual table segments (like the counters from a game of Trivial Pursuits), El Castillo wanted power and data provision, persuading the school’s in-house maintenance staff to build a rotating “lazy-Susan” in the middle of a round table with sockets in it. Ciudalcampo, on the other hand, were drawn to the different characteristics of convex and concave spaces (concave for collaboration and conversation, convex for gregariousness), and, whilst also learning how to use an electric jigsaw, built themselves bright red “splat” shaped tables. All the results had different height worksurfaces too – standing height as well as sitting height – students at Ciudalcampo found some unused lockers in the school, measured them and realised that by turning them on their side gave them a surface at just the right height for standing at. They all felt that the light levels, noise and air quality too were elements that had not been given sufficient consideration in the existing spaces. One of the schools had very 1970’s orange glass blocking out light, and most had an element of clutter that had to be cleared away (see the feature on page 34 too). Plants played a part in most of the results (breaking up noise and being used to delineate the zones) and large dry-wipe surfaces – whole walls – became a must-have for all students.

All the new learning spaces had multiple points of focus – ditching the outmoded concept of a traditional teaching wall that everybody had previously faced. Ciudalcampo repositioned the now-redundant projector to face downwards rather than horizontally, focussing it onto a table top, and then making it interactive by the use of an old Wii and the addition of some circuitry into an old stylus demonstrating ingenuity of staggering proportion and the use of just €70 of their budget.

But whilst there are similarities, there are marked differences too, because the results naturally reflected the individualities of the participants. That some students had left the school by the time the projects were completed didn’t diminish their enthusiasm – it wasn’t seen as a project “by us, for us” as Stephen reflected, “it was a project to make learning better.”