Achievement for everyone will remain elusive until there have been some fundamental reforms to our schooling system. That’s been the purpose of the book which Mick Waters and I have written which is published in January 2022 by Crown Housei.

As you would expect it argues for substantial change.

There are proposals to make admissions to schools fairer, a broader curriculum, differentiated for childhood and adolescence and based on stimulating and capitalising on pupils’ interests, together with a reformed accountability system which will have a better mix of exams and projects to assess a pupil’s progress in acquiring knowledge and skills necessary for the future rather than the past.

In this way we suggest schools will help all pupils to develop attitudes and values which will equip them to be active citizens leading fulfilled lives and contributing to the fulfilment of others. We think that exams and assessed tasks (taken when pupils are ready and based on clear criteria rather than being norm-referenced) should be set nationally, marked locally, moderated regionally with schools having Chartered Assessors within their staff and a licence to assess. And yes, we do think Ofsted should be reformed!

In summary, in the book we set out six foundation stones for making the system better and the Thirty-Nine Steps necessary to achieve a system where achievement for everyone will at last be within our grasp. If you are looking for what we should do about SEND, disadvantage, governance and finance, teachers’ initial training and subsequent development, school improvement, and leadership, our book contains detailed proposals for all those topics to usher in an age of Hope, Ambition and Collaborative Partnerships.

We came to our conclusions by examining what has worked (and not worked) in our present age of Markets Centralisation and Managerialism and by extensive interviews with almost a hundred witnesses including more than a dozen Secretaries of State for Education, around the same number of Heads of Ofsted and Senior Civil Servants and of course many more Heads of MATs, Academies, Free Schools, local authority schools, teachers and parents.

Why Equity Not Equality

And that brings me to the need to justify the title of this article. Of course, it was ‘attention seeking’, but also intended to provoke thinking, because as we wrote our book, we were at first heartened and then puzzled and dismayed by the almost universal agreement among those we interviewed,especially the politicians about the desirability of schooling as a vehicle for greater ‘equality’ ‘equity’ and ‘social mobility’ in society.

The puzzle was because we didn’t expect politicians from both right and left to agree. And then it dawned on us that they – and many others of our witnesses – meant different things when using the same words. For example, did they mean equality of opportunity, or of input, or even of outcome?

Did they mean by social mobility that it was relative – i.e. that in a meritocratic society it meant that everyone not just the privileged chance to get the top jobs but that for every one going up the mobility ladder someone had to come down – or was it absolute and that there should be a review of the relative salaries of people whom during the pandemic we have all come to call and appreciate as ‘key workers’?.

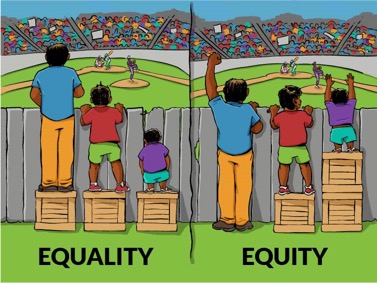

We were reminded of the need above all to distinguish what we mean by ‘equity’ and ‘equality’ and that many in education have come to realise the distinction through the following cartoon crawn by Angus Maguire (Maguire 2016) and based on work from Craig Froehleii:

Of course, the image is unidimensional – how to watch a game by giving to everybody what they need in terms of crates to stand on. It begs loads of questions for those of us in education because achieving equity through schools is much more than one dimensional. In the cartoon, for example what if one person has poor eyesight? We need more and different crates for various purposes. In schools apart from eyesight problems, there are those of hearing, neuro diversity, cognitive, emotional and/or socio-economic differences and they lead us into the world of how to ensure that all pupils, whatever their talents and interests, receive what they need to succeed.

But succeed in what way? That’s why we need to be clear about the purposes of schooling in a way we are not now: Michael Gove for example told us that ‘Every child should have access to the best that has been thought and written, every child should leave school fully literate and numerate’ … Well yes but not all pupils can. And is that all we want from schooling? So we set out in our book what we think the purposes of schools should be.

If our hope is that all pupils grow up to lead fulfilled lives as citizens who contribute to the fulfilment of others – and in general, rather than detailed terms, that’s what our witnesses hoped for – then that’s where equality will come in. But it will demand differentiated provision for pupils in school, not the same or equal for all. In the cause of equity some will need more resources and time – pupils with SEND are an obvious example. On the other hand, spending four times as much on already privileged children in private schools seems inequitable. So we suggest ‘equity taxes’ for parents who send their children to prestigious private schools.

It would not be enough to focus on issues beyond the school gate. In our book therefore, we draw attention to ‘within school’ practices. If we are serious about equity leading to a less unequal society, we will need schools where every child has a worthwhile and trusting relationship with at least one member of staff: if they haven’t, they may be physically present, but they aren’t really at school at all.

Teachers will know how and when to differentiate their approach and materials in order as one Victorian said ‘to find St Augustine’s golden key which though it be of gold is useless unless it fits the wards of the lock’. And he went on to describe the wards he had to fit in the urban equivalents to the ‘hedge schools’ he ran before he became Headteacher of Uppingham as ‘the minds of those little street boys very queer and tortuous affairs they were too. But I had to cut and chip myself into the shape of a wooden key which, however common it might look, should have the one merit of a key- the merit of unlocking the mind and opening the shut chambers of the heart’.

School also plays its part. Many school organisational details affect whether the individual teachers and their departments or phase teams can weave their magic to get closer to achievement for all. Is a school’s assessment practice truly ipsative, criterion referenced and rigorously geared towards improving on a pupil’s previous best or is it norm-referenced? Is it sufficiently and appropriately formative and not excessively summative? Do all staff in conversations with pupils about their future progress use estimate (‘pupils like you in the past on average have achieved such and such by the end of the year’) prediction (‘but in your case working as you are I predict you will achieve’) and target (‘what do you want to set as a target showing me/parents/yourself) in the same way ?

Or do staff use the terms differently and confuse the pupils? Or, worse still, are our targets top-down? Do we link with local clubs and societies such as those for sports and the performing arts so that young talent can access expert coaching and practice to take them on a motivating journey to becoming highly skilled and proficient/? Do we have three parts of Appreciative Inquiry for every one part of Problem Solving both in our classrooms and in our school and departmental team meetings? The questions crowd in and there’s always room to do more.

Unfavourable Comparisons

In researching our book, we were truly distressed by one aspect of schools’ practice which illustrated an unfavourable comparison between what happens in England and what happens elsewhere. That was the question of inclusion. The reverse of that – pupil exclusion – reveals a sorry picture. In 2018 7,720 pupils were permanently excluded from English maintained schools. (That’s not counting the many more pupils either ‘off-rolled’ or ‘counselled out’) In Scotland a tenth of the size of England the figure was not 772, not 77 but 5: for every child excluded from a Scottish school, therefore, 1,500 are excluded in England.

What shocked us most was that none of our witnesses knew the scale of the problem, and none had visited Scotland to find out what they do differently. Michael Gove, himself a Scot, called exclusion ‘a necessary evil’: we disagree – it’s simply an evil. As research shows Scotland has a totally different approach involving the use of language (they talk about ‘relationships’ not ‘behaviour’ and ‘discipline’) a different broader curriculum and more diverse, high quality, ‘alternative provision’. Nor do they have, as we do a so-called ‘Behaviour Tsar’. We in England should visit and learn.

Our book attempts some answers to these dilemmas in pointing the way towards what we hope and believe will be a new age of Hope Ambition and Collaborative partnerships when there will be fewer obstacles to those committed to achievement for everyone.

Sir Tim Brighouse was the Chief Officer of Birmingham Education Department and the Schools Commissioner for London between 2002–2007, where he led the London Challenge.

References

i Brighouse T Waters M (2021) ‘About our Schools: improving on previous best’ Carmarthen: Crown House

ii Froehle, C. (2016, April 14). The Evolution of an Accidental Meme. Medium. https://medium.com/@CRA1G/the-evolution-of-an-accidental-meme-ddc4e139e0e4#.pqiclk8pl

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month