Despite the myth busting that has taken place, our education behaviours concentrate on test-based, rather than trust-based, approaches to improving the whole system.

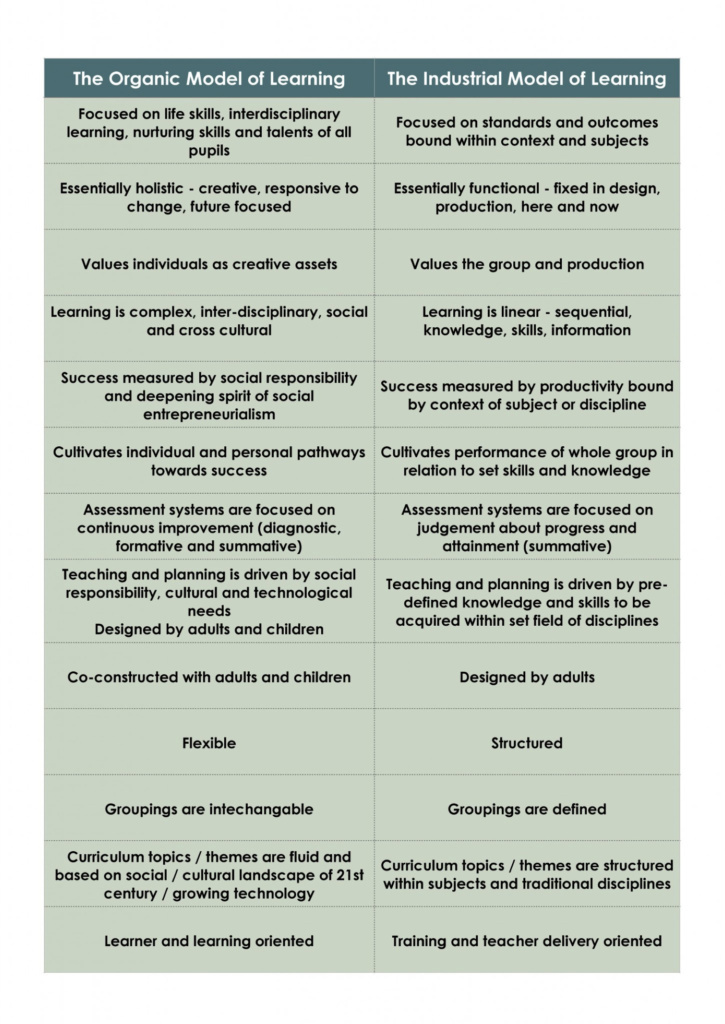

Learning-centred leadership celebrates the teacher/leader as designer (one who understands the beauty of his/her craft) instead of industrialist (a mass producer of outcomes). School improvement which displaces the final outcome as the goal, placing creation and shared ownership at the centre, imbues a collective sense of worth. Stuff that is done for quick wins, functions or efficiency wears us down.

For a generation of teachers, school improvement practice is not authentic and is potentially damaging to the profession. Formal book looks, whole-school progress review meetings and monitoring tends to be an event, not a process. It is artificial, stage managed and delivered so that we play the role of leadership. This makes us think in leadership actions not interactions. There is a perception gap between the true impact of formal monitoring and its intended impact. In other words, just because you have monitored books, it doesn’t mean it has made a blind bit of difference.

It doesn’t have to be like this though. Giving permission for teachers to lead their own self-evaluation, making school improvement a collaborative process has the double advantage of:

- Growing skin in the game (e.g. helping teachers learn from experience)

- Creating agency amongst staff to find solutions to common school challenges.

Within Inspire schools, a good example of design leadership came from the development of our maths feedback stickers. The idea began from classroom recognition that practice could be better – a reason to change – and a cross partnership commitment to deepening learning through collaboration. The iteration of the design was inherently organic, collaborative, social (involved staff doing stuff together), and a bit messy. The impact, on the other hand has been phenomenal! An unintended consequence? Students too, became fully involved in guiding their learning, using the feedback prompts independently, to accelerate their own learning; deepening critical thinking and reasoning.

There are some key lessons:

- The best school improvement is authentic because it is driven from a genuine cause, a necessity which is real

- Teachers are the most powerful change agents because they have ‘skin in the game’ (they understand best the struggle of implanting change or the potential impact of this change).

- Change is not linear

Most recent education policy initiatives have been aimed at simplifying teaching. For example, promoting text book learning or assuming Asian mastery models for teaching can be lifted and transplanted into our schools. It supports a theory that improvment moves predictably in a straight line – making it easier to track or by pulling levers: more phonics, more discipline, more testing, more mastery teaching. In other words, an ordered, logical, sequential approach to school improvement – a delivery model instead of a design model. We have encouraged schools to play safe, follow the rules, take fewer risks. The trade-offs are quick wins, measured by headline grabbing policies against the long-term investment in professional judgement and an educational values base crafted to meet the needs of 21st century learners. We have reduced the life changing work teachers do to a binary metric. This effectively simplifies teaching to tasks or outputs instead of recognising the complexity of learning as an exchange, an interaction, a combustion of multiple experiences, splattered with ‘useful learning mistakes’.

By contrast, real teacher leaders have ‘skin in the game’. Skin in the game requires risk taking, mistake making and understanding that organisations are complex – relationships driven. Successive education policy has largely been created by policy wonks who have limited understanding of the complexities of school leadership. Their role models and reference points for what an education system should be like come from each other and their own (equally limited) experience of schools, hence not much changes and the cultural biases, cognitive dissonance and other forms of blindness continue.

These are people whom Nassim Nicholas Taleb argues have an absence of ‘skin in the game’. They design education policy that fits their schema of what learning should be like because it replicates the experience of their own education. These people have never taught, struggled, lived life in fear of a dodgy inspection or had much to lose. They rarely cross the social boundaries beyond their immediate ones and tend to spend most of their time locked in the same environment – with similar thinking people. Their knowledge of disadvantage, social injustice or inequality comes from what they have read, or worse, from statistics, rather than what they have experienced. But still, these are the people who mandate policy and strategy in education.

For a better, more enduring and authentic education system, we have to be brave, take risks and value the journey of learning. We need more designers than industrialists.