The pandemic has unmasked and exacerbated existing social, educational and economic inequities [1]. It has also brought into focus the drastic scale of the digital divide [2] in raising the profile of digital poverty and exclusion. Both within the UK and across the globe, we witnessed children, young people and adults completely unable to access their education due to a lack of digital devices and internet access in their lockdown environment. [3]

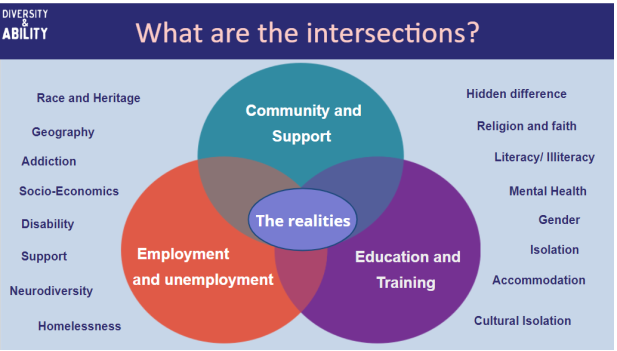

Our attempts to simultaneously, live through and recover from the pandemic, need to be founded on a deep understanding of truly intersectional inclusion. We need to acknowledge that we have tangible tools at our disposal to make our environments more inclusive for everyone; those tools are assistive and inclusive technologies.

Defining intersectionality in the context of digital poverty and education

The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1991 [4]. It’s defined as the understanding that we are made up of many different aspects of our identities, some of which are characteristics for which we experience marginalisation in society. This could include our race, gender, disability, neurodiversity, class, and other aspects of who we are. The crucial aspect is that our identities don’t exist in siloes; they intertwine and interact to shape the way we see and experience the world. As Audre Lorde said: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” [5]

In education, we often witness aspects of our identity segmented into individual ‘issues’ or areas in need of support. As an organisation, with our roots in the lived experience of disability and neurodiversity inclusion, we often see this where disability or ‘SEN’ initiatives are the focus. Although, to focus purely on SEN is to try and create a reality that doesn’t exist; one where our neurodiversity is the only aspect of our identities and experiences, and the barriers we face.