The Covid-19 Pandemic has created an unprecedented challenge for educators, parents and children with a key question: “How do we sustain children’s learning when they are away from school”. Every teacher knows that when children are off school in the summer their learning moves backwards. Where that learning was embedded and established it can be retrieved, though it does take time. However, where learning is not sufficiently embedded it is likely that it will be lost altogether and need to be retaught. The biggest losses will be for the most disadvantaged children who may not have access to books or support at home.

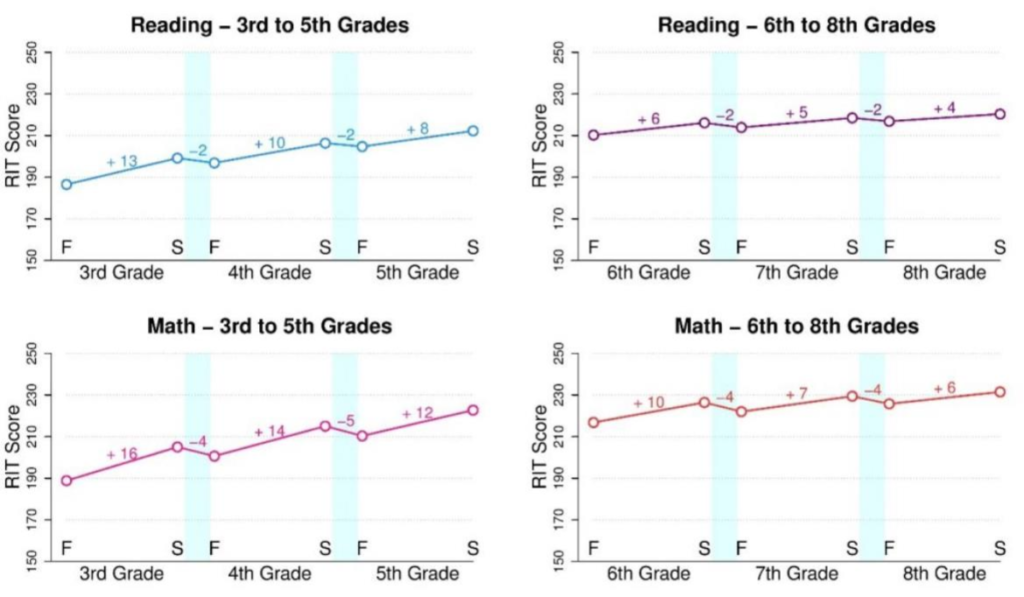

In the US the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) research into Summer Learning Loss¹ based on a 10-week vacation period showed on average, students show a drop of between 3-5 RIT points, relative to gains of 4-16 RIT points during the school year. In effect students lose nearly 20 percent of their school-year gains in reading and 27 percent of their school-year gains in math. By the summer after seventh grade, students lose on average 36 percent of their school-year gains in reading and a whopping 50 percent of their school-year gains in math. In other words, summer learning loss increases with age through elementary and middle school. RIT scores use the Rasch Unit Scale to allow analysis across a range of different testing schemes and there is no equivalent system in the UK but teacher assessments show equivalent changes as evidence in my own research.

Drawing on my own recent research into the development of reading skills, particularly what parents would understand as reading comprehension – not just what the words say and mean but the deeper meaning of stories and characters that bring books to life – it is clear that with a prolonged absence from school, without action at an individual local and national level, reading standards will decline and with it the life opportunities of a whole cohort of children will be damaged.

Reading Gains Of Up to 35%

The one-year research project undertaken in 8 schools in Slough from January 2019 was designed to improve these higher order skills and was highly effective, increasing the % of pupil achieving at or above the expected level by more than 35% in in Year 3 and 25% in Year 4 in just 5months. However, with the break over the summer holidays (7 weeks allowing for start and end of term loss), pupils achieving at or expected levels declined significantly. Despite their hard work and the commitment of their teachers by the end of November they were still performing less well than they had in June

in fact the percentage of pupils achieving the expected level or better was down by more than 20% in Year 4 and almost 15% in Year5 taking us back towards pre-project levels.

If this can happen in 7 weeks how much learning and progress will be lost over 12 weeks or longer and for children in the most disadvantaged families where books, time and opportunity for reading with an adult are often missing to what extent will they stop engaging in reading all together beyond completing set tasks for school.

In the current situation it is likely that children will be off school for a sustained period and we cannot fully predict the impact of this however we can be certain that it will have a negative impact.

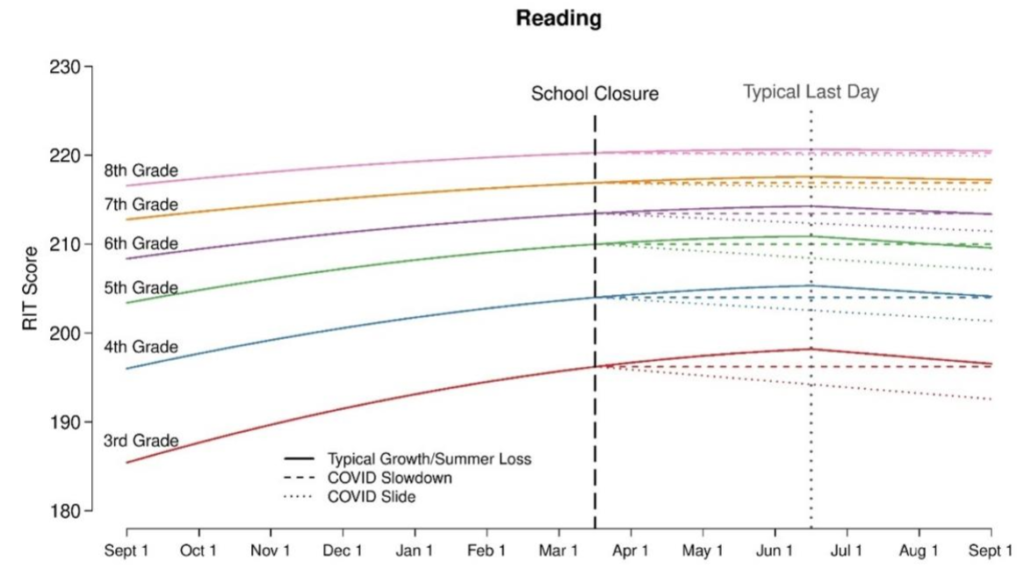

Some early predictions show a very challenging picture. Based on data from the US where summer holidays are usually longer than in the UK the following slide shows a predicted additional impact from the Covid-19 closures. ²

Schools are doing all they can with teachers setting on-line lessons and signposting digital learning platforms but I believe that unless we highlight the importance of reading and help parents understand that reading is not an individual and private activity but one that requires discussion and reflection in order to acquire and sustain the skills of “being a reader”.

Reading Accurately

Many parents regard reading as the skill of decoding words and knowing what the words mean – this of course is central to the process of reading but being able to do this does not make a child a reader. When I was a headteacher I had to frequently remind parents that the reading we set for homework required them to listen to, read with and discuss books because once children could read independently they saw no reason to listen to them – they would say that they didn’t want to read aloud, that they liked to read in bed at night, all of which may be true but it leads to children reading inaccurately and skipping over things they don’t understand and missing the opportunity to draw on the deeper meaning in a book.

The most crucial years for this are Year 3 to 6 when children should be gaining these higher order reading skills but this is exactly when parents see them as independent readers and spend less time reading with them.

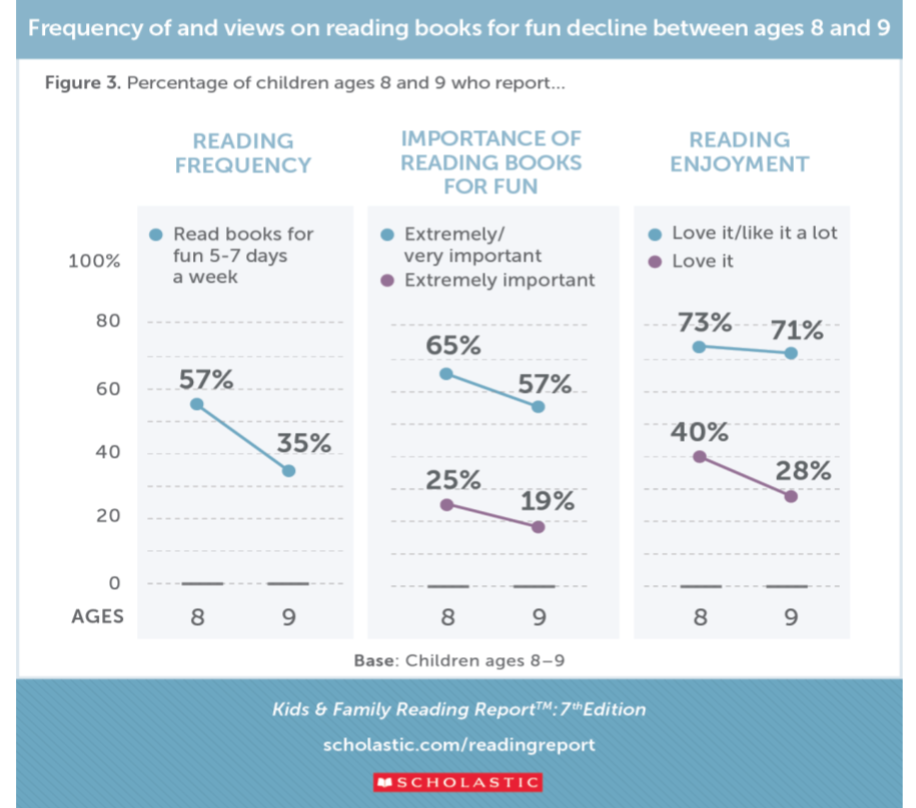

Children’s attitudes to reading and reading frequency is an important predictor of pupils’ proficiency as readers and there is a significant decline in pupils who value reading for fun between the ages of 8 and 9. This coincides with a decline in parental engagement with reading “as one in five parents of children ages 6–17 (21%) stopped reading aloud to their children before age 9, most often citing reasons related to their child being able to read independently” ³

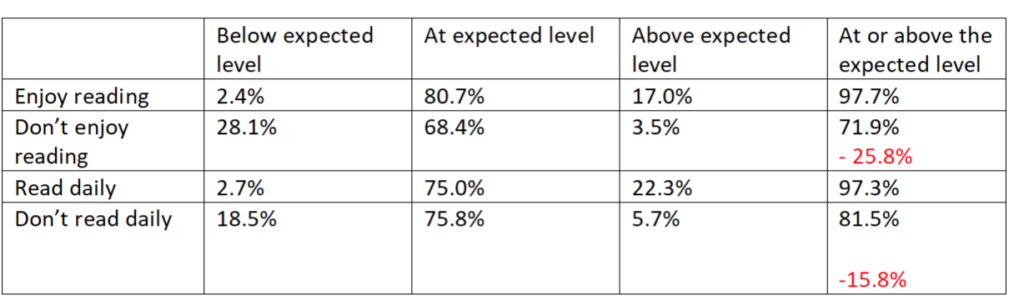

The opportunity to read together interactively in school and at home it impacts not just on pupils’ progress in reading but their enjoyment of reading and it increases their confidence, competence and feelings of security as shown below. ⁵

The core factors in the development, particularly of higher order reading skills, are:

- A shared responsibility – where reading is done with children both at home and at school rather than being done to or done by children;

- Frequency – since it is clear from the research that pupils who read more frequently make better progress with their reading;

- Continuance – which allows the learning and the learning habits to build over time and carry on even after the basic skills of reading are mastered;

- Quality – to ensure that the nature of the interaction is rich and developmental.

However supporting parents to engage meaningfully in interactive reading is a huge challenge, not only do we have to find ways to support parents to commit time and effort to a task they may see as being the teacher’s responsibility but we have to mitigate for the fact that many parents may face additional challenges such as low literacy, high workloads, health conditions or speak English as an additional language and in addition there are many homes where there are no books.

There is strong evidence that the vast majority of parents understand that reading well is important and there is powerful data that schools can use to show parents that children who enjoy reading and read frequently do significantly better than their peers who do not. And children who read with their parents regularly will therefore be more likely to make good progress.

The Biggest Challenge

In this time of national crisis, it is important that schools plan strategically using their resources to best effect to help sustain learning and progress and to engage parents and pupils in a collaborative endeavour to deliver the aspects of learning and support which are difficult if not impossible to deliver remotely.

If we address these issues now there is much that we can learn and apply to address the summer learning loss that is impacting on pupils every year.

The biggest challenge in improving pupils reading skills is to support parents to understand how challenging it is to read with real meaning. We have to consider all the things that we take for granted about reading based on our own life experiences and then build them into the way we support children to “become readers rather than children who can read”

For example – reading is a fun shared experience, books can help you understand a wider world than you will ever experience, the more you read the more you want to read, you can use your own imagination to bring books to life – authors often leave us to picture a character or a place for ourselves, just as in real life people in books often don’t say what they mean or we don’t know what they are thinking. Children need access to a range of books and the social interaction to explore them fully. This is about creating a reading culture that enables children to reflect on and learn as they are read to and read and hear people talking about books.

We need to support parents to understand how to talk about books and share the reading process and we need to ensure that pupils have access to a range of books to engage and challenge them.

The EEF⁷ has undertaken significant research it to effective home reading programmes to address the summer learning loss. They note that there are surprisingly few high-quality evaluations of parental engagement interventions on children’s attainment, and many of the more rigorous studies show mixed results. They note that just giving children books won’t be effective, their advice includes:

· Giving tips, support, and resources to make home activities more effective—for example, where they prompt longer and more frequent conversations during book reading.

· Carefully selected books plus advice and support specific to those texts

They also note that there needs to be a focus on the skills you want children to develop at different ages including:

• in the early years, activities that develop oral language and self-regulation;

• in early primary, activities that target reading (for example, letter sounds, word reading, and spellings);

• in later primary, activities that support reading comprehension through shared book reading; and

• in secondary school, independent reading and strategies that support independent learning.

Taking action

We need to act now while the routines of social isolation and home schooling are being established and find ways to support parents to work with their children and sustain their reading development including asking a range of questions about the book they are reading together using the ‘five Ws’—who, what, where, when, and why; asking them to summarise what has happened in the book or story so far, and to predict what will happen next; making links between the book and real life, to develop their understanding of ideas in the book.

We need to make reading a fun social experience (whether it is at home or at school when things get back to normal) and ensure that reading at home is a purposeful part of their wider learning not a chore which has to be completed.

We need to engage in a dialogue with children listening to their views about reading, but also helping them to understand the importance of ongoing engagement in reading so they are proactive when reading at home.

We need to urge parents to use as much of their social isolation time as possible on reading with their children and provide them with guidance on how to do this effectively.

We need to find innovative ways to get books into the homes of every family so that children can benefit from the sort or reading environment they have at school.

We need to encourage schools and individual teachers to inspire parents with model reading sessions and fun on line reading adventures and signpost the pod casts and reading broadcasts that many well-known authors are creating.

We need to urge the media to produce programmes that promote books and reading on TV, radio and through podcasts and video clips.

And perhaps when many grandparents are confined to home, we should urge them to use Skype or Facetime to read stories to their grandchildren on a daily basis – “Listen with Grandad and Grandma”

And for the future we consider not just how to address the summer learning loss but to look more radically at the pattern of the school year based as it is on a traditional; of Christian festivals, factory closures and harvest time and consider if this is fit for purpose in the 21st Century.

Every Child A Reader – Some Materials For Action

As a starting point in the current situation I have produced some guidance for parents to help them understand what we mean by comprehension – the domains of reading – and to illustrate how pupils can progress in their skills and knowledge using a modified rubric. As a practical tool the three PowerPoints model the process of sharing a book interactively so that parents can explore picture books, chapter books and non-fiction texts with their children.

For A Knowledge Bank full of related resources from the Every Child A Reader Pack, please click here!

Heather Clements is a former primary school headteacher, Director Of Schools for a London Borough and currently works as an education consultant.

References:

- Megan Kuhfield; NWEA research into Summer Learning Loss 2018 Blog

- Megan Kuhfield: Covid 19 School closures could have a devastating impact on student achievement 2020 Blog

- Scholastic. (2016b). Kids and family reading report United Kingdom. Retrieved from www.scholastic.co.uk/readingreport

- Scholastic. (2015). Kids and family reading report (5th ed.). Retrieved from www.scholastic.com/readingreport/key-findings.htm#top-nav-scroll

- Margaret Kristin Merga: Interactive reading opportunities beyond the early years: What educators need to consider. Australian Journal of Education 2017

- Children and young people’s reading in 2017/18 © National Literacy Trust 2019

- WORKING WITH PARENTS TO SUPPORT CHILDREN’S LEARNING Guidance report authors: Matthew van Poortvliet (EEF), Dr Nick Axford (University of Plymouth), and Dr Jenny Lloyd (University of Exeter).

- Allington, R. L. and McGill-Franzen, A. (2017) ‘Summer reading loss is the basis of almost all the rich/poor reading gap’, in Horowitz, R. and Jay Samuels, S. (eds), The Achievement Gap in Reading: Complex Causes, Persistent Issues, Possible Solutions, New York: Routledge.

- Kim, J. S. and Quinn, D. M. (2013) ‘The effects of summer reading on low-income children’s literacy achievement from kindergarten to grade 8: a meta-analysis of classroom and home interventions’, Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), pp. 386–431.

- Maxwell et al. (2014) ‘Summer Active Reading Programmes’, London: EEF.

- David M. Quinn and Morgan Polikoff 4, 2012017 Summer learning loss: What is and what can we do about it?

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month