The imperative to change

As another lock down seems to be slowly heading towards an end, we need to stop and reflect on what we have learned through about the teaching and learning experience, and ways that the different way of teaching that we have had to implement may actually be able to teach us something for the future.

There is no doubt that many of us have not been able to simply deliver the same materials we might have done had we been in school. Asking students to follow a PowerPoint from home for five or six hours a day was quickly seen as folly and work needed to be broken down, the pace slowed and infinitely more scaffolding was required. Now, more than ever we need to reflect on the science behind learning and consider the impact of Cognitive Load Theory and ‘how much is too much’. See also the earlier article in this issue of PDT for a detailed overview of Cognitive Load Theory.

Pressure on teachers and learners

The implications of teachers having greater awareness of cognitive science are potentially profound; however, we must also factor in the ever-increasing workload being placed on us all and be in a position to use the aspects that are most useful to us. What we need from our professional development is an understanding of key principles as well as some direct strategies to support our students.

Although the public examination window has been cancelled again this year there is no doubt that education has created an endless pressure of completing a Scheme of Work by a given date, leading to teachers having increased pressure chasing Years 10 and 11 students for work so the next topic of the GCSE curriculum can begin; but how much does it actually achieve? Are we really helping the students or ourselves by forcing everyone to race through topic after topic? Do all of our students need to know everything we can possibly throw at them in time for their exams? In short, how much is too much?

Information overload!

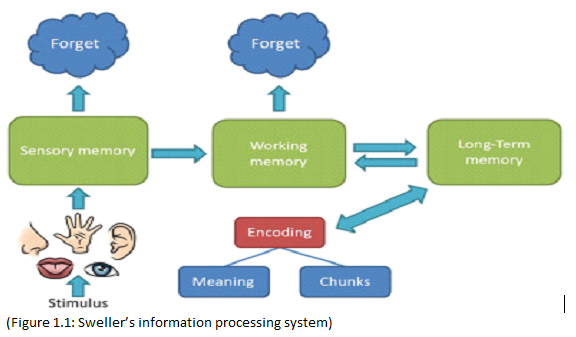

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) was first published in April 1988 by Emeritus Professor John Sweller, of the University of New South Wales, Australia. Put simply what Sweller was suggesting was that our brains can only take so much new information on board at once. Our working memory, which is located at the front of the brain retains information for immediate retrieval but is limited in its capacity, whereas our longer-term memory, located at the back of our brain, is able to withhold endless amounts information for years, without even getting close to its maximum capacity.

The magic question is, therefore: how much can our working memory hold? Research clearly shows that the average adult can retain seven pieces of information at any one time. G.A.Miller coined this as the ‘Magic Number Seven’ in 1956 however this still holds true today. If we assume that the average student will not yet have full adult mental capacity by virtue of the fact, they are still developing and then combine that with the fact that an ever-increasing number of young people have additional needs to cope with as well this clearly has some profound consequences for our teaching.