The power of the question

This article is about the process of planning research so that it is effective and manageable. It aims to provide:

- an overview of the research process

- guidance on planning a research project effectively

- case-study examples and ideas for effective planning

- links to other sources of information.

- An overview of the research process

What is research?

A commonly cited definition of research is Lawrence Stenhouse’s (1975) view of research as ‘systematic inquiry made public’. This definition emphasises the systematic and enquiring nature of the activity, and the importance of sharing findings publicly. In schools and colleges, research can take many forms, ranging from individual projects to whole-school or network-wide initiatives (see Box 1.1).

What does research involve?

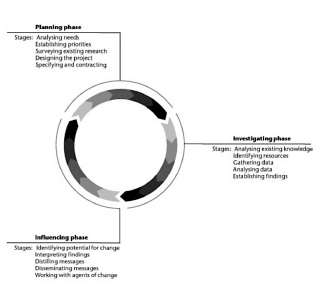

While the examples in Box 1.1 vary in many ways, it is possible to think of all of them going through a number of similar phases.

As shown in Figure 1.1, the research process can be seen as involving a number of interconnected phases. So this guide focuses on how the initial planning phase can be carried out successfully.

Box 1.1 Examples of research:

- Primary school reception staff undertaking classroom research on ‘learning to learn’ with support from senior staff and an external researcher.

- Two members of staff in an Early Years’ Centre evaluating the use of video conferencing with young children, as part of the local Education Action Zone.

- A secondary school deputy headteacher doing a small research project to identify the curriculum needs of students at key stage 3 before investing in new materials.

- Several further education college tutors looking into the learning support needs of part-time learners as part of a regional Learning and Skills Research Network project.

- An individual teacher undertaking a project on staff development for a university research degree.