Making evidence accessible, accurate and actionable

This article provides an overview of the Toolkit the Education Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) Teaching and Learning Toolkit and summarises what I see as the potential contribution it makes to research-informed teaching and to professional development and learning in schools. It focuses on the challenges of making evidence both accessible and accurate as well as in a way that is sufficiently actionable to ensure improvement. Publishing summaries of evidence doesn’t automatically translate into schools improving their teaching practices. Sometimes people misinterpret what you intended.

I’ve heard accounts of schools devoting extra hours to marking pupils’ work under the impressions this would deliver effective feedback. Marking pupils’ work focuses on feedback delivered and the efforts of the teacher, but not whether the feedback was received, understood and acted upon by the learner. One local authority in Scotland attempted to use the information in the Toolkit as justification for increasing class sizes, ignoring the finding that pupils in larger classes tend to do a little bit less well, on average. The overall argument is that reducing class sizes is only moderately effective and very expensive, so it is not cost-effective as a strategy to help learners. Challenges like these are at the heart of research-informed teaching.

The EEF’s Teaching and Learning Toolkit

The Toolkit was originally funded by the Sutton Trust to summarise evidence from educational research to challenge thinking about effective spending for what was then the new pupil premium policy in England. This policy aimed to increase spending in schools to benefit children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. The Toolkit was subsequently adopted by the EEF and is now in widespread use in England, with just under two thirds of headteachers saying they consult it. Similar approaches to evidence synthesis and translation, as well as adoption of evidence in policy-making, are growing in popularity, reflecting a global movement towards more effective engagement with research and evidence.

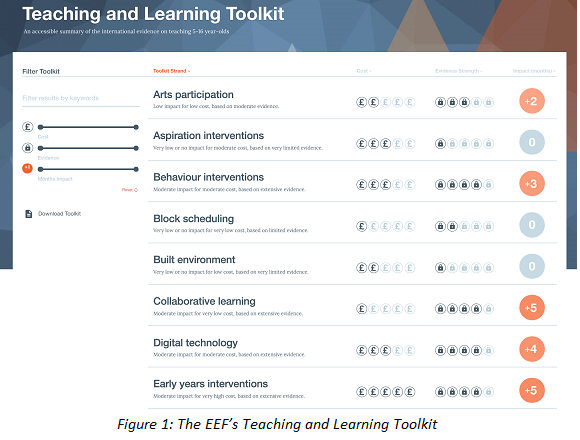

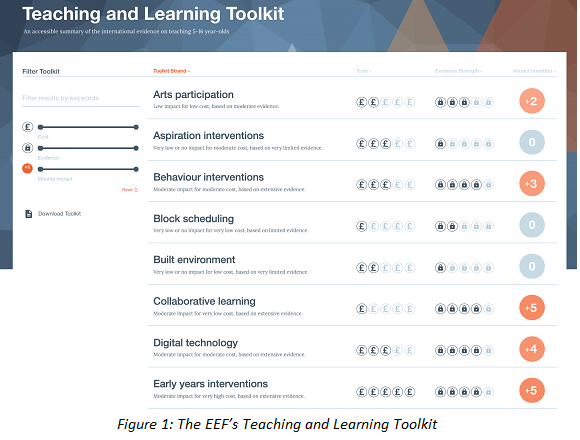

In the Toolkit a number of educational approaches or programmes are listed, and categorised in terms of the evidence from research for their effectiveness, the cost and average impact. The aim was to create something like a ‘Which?’ consumer guide for education research, covering topics of interest and relevance to policy and practice. The UK Government has cited the Toolkit as an exemplar for its network of ‘What Works’ centres. This commitment to spend public money on the most effective practices is important and impressive, but the ‘What Works’ label can imply a certainty that I believe oversimplifies what the research actually means. Research can only tell us what has worked in the past, not what will work in the future. I argue further that it can only offer indications of what may work under certain conditions.

The Toolkit website (see Figure 1) summarizes the messages across different areas of education research with the aim of helping education practitioners make decisions about supporting their pupils’ attainment in schools. It is designed to be accessible as a web-based resource for practitioners and other educational decision-makers. It combines quantitative comparisons of impact on educational attainment in an approach sometimes called ‘meta-synthesis’. This is where the findings from different meta-analyses are combined to give an overall effect. This is similar to, and was inspired by, John Hattie’s approach in Visible Learning. The aim of the synthesis is to provide information and guidance for practitioners who are often interested in the relative benefit of different educational approaches, as well as information from research about how to adopt or implement a specific approach. What distinguishes the Toolkit is the inclusion of cost estimates for the different approaches to guide spending decisions along with an indication of the robustness of the evidence in each area.