Safer Internet Day

Have you noticed how many adverts there are for gambling? Once you get past 9 pm on commercial television channels it seems as if every other advert is for bingo, bookies and betting companies.

This impression is borne out by statistics. In June last year the first two Premier League matches featured 24 separate gambling adverts in commercial breaks. It was so noticeable that it prompted the Daily Mail to accuse gambling firms of ‘providing the gateway for the next generation of harm’. During the World Cup in 2018, BBC research analysed 11 games broadcast on ITV. 62 of the 66 commercial breaks contained one or more gambling advertisements.

Then there are raffles – the mainstay of fundraising for charities. One of the ironies is that if you go online to look for advice on gambling from the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) you will find their Responsible gambling guide – NSPCC and just three entries further down the page, Play our raffle | NSPCC.

This typifies our mixed response to gambling in the UK. ‘It’s just a bit of fun’, but an increasing number of gambling clinics are being set up to help the 224,000 adults (0.4% of the population) ‘higher risk problem gamblers’, and the two million (3.6%) who have been classified as being ‘at risk’ of developing a serious gambling problem.

The difference technology makes

Many children start gambling via arcades and similar places, perhaps at fairgrounds and the seaside, having fun with their parents, moving from hook-a-duck and the grab-a-toy to fruit machines. There were signs that there was a dip in gambling with lockdown when pubs and amusement arcades shut down.

Type ‘heroin’ or ‘alcohol’ into a browser and page one gives you Wikipedia entries and health warnings. Type in ‘gambling’ and you have to scroll past a slew of gambling adverts for ‘free spins’, ‘instant cash on your winnings’, ‘fast payout’, ‘£10 bonus’, ‘sign up now’.

Now, with cookies these adverts will not just be on Google but will pop up on social media and in junk mail and so those with a gambling problem will be faced with near constant temptation and even more opportunities to gamble.

For as long as people have gambled, there have been gambling addicts, but they usually had to go out of their homes to ‘scratch the itch’.

Over the past 15 years, there has been a relaxation of rules for the gambling industry, coupled with more sophisticated technology and faster internet, so gambling has come out of arcades, betting shops and casinos and into children’s bedrooms.

The current state of play

Gambling often used to be closely linked to real world events such as betting on the result of a football match or the winner of a TV show. With technology, the real world is irrelevant and young people can gamble round the clock in a virtual fantasy world.

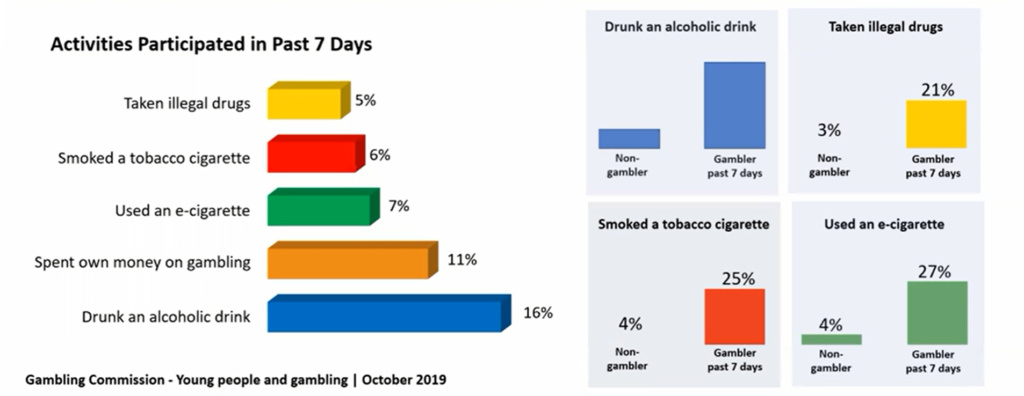

A report by the Gambling Commission last year estimated there are now 55,000 regular gamblers aged 11-16 in England, Scotland and Wales, and 350,000 who gamble regularly. In this age group, gambling is more popular than smoking or taking drugs; 11% of 11 to 16-year-olds reported that they had gambled in the previous week, compared to only 6% who had smoked tobacco and 5% who had used illegal drugs.

Perhaps part of the reason lies in the fact that teenagers are quite lethargic. They would need to make an effort to get cigarettes and drugs but can gamble 24 hours a day without even getting out of bed.

The link with gaming

Many young children enjoy games on their phones or tablets and find them a great way of relaxing and escaping from the tedium and pressures of day-to-day life. A recent study of the most popular desktop videogames showed that more than 70% of games – even some designed for young children – now contain ‘loot boxes’. This is all part of a drive to monetise games and increase profits. Loot boxes let players use points or virtual currency or, in some cases real money, to open a box that contains a mystery item.

The Immersive and addictive technologies Fifteenth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, published in September 2019 by the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee, make a link between loot boxes and gambling:

‘They are a common form of microtransaction, with a 2018 Gambling Commission survey finding that 31% of 11–16 year olds have paid money or used in-game currency to open loot boxes.140 Although some games (including, notably, a version of Fortnite) reveal the contents of a loot box to the player before they decide whether to pay for it, usually the contents of loot boxes are unknown to the player at the point of purchase—what a player gets for their money is therefore based on chance’ (page 27)

They also cited evidence from Ben Lewis Evans, a user experience researcher at Epic Games, who gave a presentation called ‘Reward Psychology—Throwing out the Neurotrash’ and talked about the reward mechanics behind devices like loot boxes in games such as Fortnite: ‘The reason these are famous is they are quite often the ratios used in gambling. The response they tend to get is a very constant and high-level response and that’s because you don’t know how many times you have to respond before you get the reward, so people tend to keep it up.’

How games hook children in

These days it seems that the line between games and gambling are blurred. They often look and feel similar. Both purport to be entertainment, often share a ‘freemium’ model so players are tempted in by freebies but pay extra for enhanced features, and are linked in to a community of other players.

- Online games are lively, fun, attractive and appeal to the senses

- Many require little or no skill to get started

- Players enter a beautifully realised fantasy world where they can forge a different identity and have any qualities they desire

- There is constant encouragement, so players don’t feel they are losing but that if they try a little harder, have a little more luck, they can be a winner

- There is no beginning, middle and no sense of an ending, just levels, so they never need to leave that world

- There is often an in-game currency so they don’t feel as if they are spending real money, although they may be encouraged to make in-app purchases to increase their chance of success

Gaming used to be seen as a solitary activity but now many require players to interact with others, so games fulfil a social need. Sometimes a game will move forward even when the player is not participating, so there is the fear of missing out or being left behind. This ensures that most children won’t wait too long before going online and will become distressed if something happens that stops them checking in. Games can build a sense of community as individuals work together on a shared quest. It gives a sense of belonging but can all too easily damage real-world friendships, especially if the child stays at home and loses contact with class mates.

Can gaming be an addiction?

Gambling online offers many rewards from constant feedback and praise, to points, virtual high fives, clapping and cheering. The player is never a loser but experiences near misses. The rewards keep them hooked and their brain releases dopamine, a feel-good chemical, which keeps them motivated, happy and energised. This coupled with adrenaline and endorphin rushes that players experience makes for a very intense experience and the real world can seem pale and insipid in comparison.

According to the NHS website, ‘Gaming disorder is defined by the World Health Organization as a pattern of persistent or recurrent gaming behaviour so severe that it takes “precedence over other life interests”. Symptoms include impaired control over gaming, increased priority to gaming and continuation or escalation of gaming despite negative consequences – such as the impact on relationships, social life, studying and work life or spiralling financial costs.’

Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust conducted research looking at over 2,000 university students and their attitudes and behaviours in relation to gaming and gambling. Their survey shows that 47% of university students have gambled in the last 12 months. Of these:

- 1 in 12 can already be classed as a problem gambler

- 8% of student gamblers have used all or some of their student loan to gamble 56% are seriously considering dropping out of university

- 1 in 10 has run up debts of more than £10,000

The problems are likely to get worse. It is easy to see how university students in lockdown may well move on from sprawling in front of the TV to watch Countdown in the afternoon, to spending time online, immersed in a virtual world which offers a promise of a reward, if not now then some time in the near future.

What are the dangers?

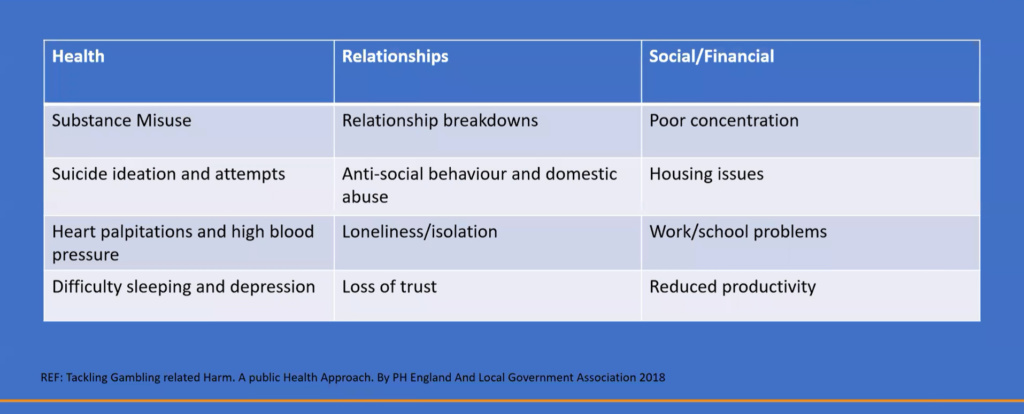

The downside is that gaming and gambling tend to be solitary, unsocial activities where people are not making friends or developing their social skills. Instead, they are isolating, often cutting themselves off from family and real-world activities. They can so easily end up gaming all night, keeping themselves going with high energy drinks and fast food so their moods are affected.

Families report that young people struggling with a gambling habit often tell lies about the amount of time and money that they are spending, and their relationships further deteriorate as they become more secretive.

What can we do?

Out-of-control gambling is linked to complex individual and social problems – including stress, anxiety and other mental health issues such as bipolar disorder. CBT attempts to tackle the behaviour by dismantling some of the common beliefs and attitudes around it. Gamblers may be encouraged to set themselves realistic limits, fulfil their financial obligations before spending on betting, and to think of gambling as a form of entertainment as opposed to a means of making money.

At Innovating Minds, we have been working with Young Gamers and Gamblers Education Trust (YGAM) a national charity that helps young people make informed decisions and understand more about the risks of gambling and gaming. They have provided a webinar which you can access from our EduPod site for the next twelve months. They also have over 450 resources for primary schools, secondary schools aligned to the PSHE and RSE programmes of study, as well as the PSE curriculum in Wales suitable for PSHE tailored to different age groups.

Other solutions

Other countries are taking steps to deal with the issue at a government level. South Korea has introduced a law banning access for children under 16 from online games between midnight and 06:00. In Japan, players are alerted if they spend more than a certain amount of time each month playing games and in China, internet giant Tencent has limited the hours that children can play its most popular games.

As yet, in the UK we have little legislation to protect our children and young people from the impact of online gaming and gambling so we need to focus on getting the message out to schools, youth groups, and especially in lockdown, to parents and to students.

For further reading

/Innovating Minds: https://www.innovatingmindscic.com/ I

EduPod webinar: https://www.myedupod.com/youthgamingandgambling

https://www.begambleaware.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/yougov-covid-19-report.pdf

https://www.begambleaware.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/yougov-covid-19-report.pdf

YGAM also have further resources for youth workers and other professionals working directly with young people, helping to increase awareness amongst practitioners and to educate and safeguard young people. For further information contact Lucy Gardner lucygardner@ygam.org

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month