‘Excluded from School’ is an outstanding resource. It provides an excellent grounding for professionals working with children and young people who are vulnerable and at risk of exclusion: social workers, educational psychologists, teachers in schools and pupil referral units, learning mentors and local authority policy makers. While it is written by highly skilled professionals, the book also reflects the views of children, families, schools and all the other agencies involved.

‘Why is it that we exclude from mainstream schools, and keep excluded, some of the most vulnerable and troubled children and young people in our society?’ asks Mike Solomon. This question is at the heart of ‘Excluded from School: Complex Discourse and Psychological Perspectives.

Written by Christopher Arnold, Jane Yeomans and Sarah Simpson, with contributions from other experienced psychologists, Part One of the book outlines the history of exclusion. It examines from different psychological perspectives the motivations that lie behind segregating individuals or groups and the consequences that ensue.

Part Two features five case studies where the authors provide testimonies from people who have been at the centre of school exclusions: the child, the family, teachers, senior leaders at the excluding school, family agencies, social services and the school or PRU that accepts the child post-exclusion.

Schools and families on a collision course

This scenario will be familiar: a 12-year-old boy starts to behave badly at school. A meeting is arranged with the family. Together they agree that the child would benefit from counselling and the child joins a waiting list. After many months, the child is offered an appointment but refuses to attend the counselling sessions, so the service closes the case. The school feels the issue lies with the family; the family feel the issue lies with the child; the counselling service feels the school has not been proactive. If only the services would work together! This child is likely to be excluded because no one understands what is going on in his head and there are currently limited options for supporting him.

The authors describes this as ‘pass the parcel’; others see it as a merry-go-round. Many factors affect the child: biological and psychological (by nature or nurture) forces and social pressures. However, there are competing factors which influence school policy too: Ofsted, exam results, school tables and maintaining the number of pupils on the school roll.

Dr Mike Soloman, formerly consultant clinical psychologist at the Tavistock Clinic and the London borough of Camden Secondary Behaviour Support Service, points out: ‘The pressures to create a stable set of indicators showing school performance can create situations which are not conducive to working with very unstable children.’ Rigid systems do not take into account children in turmoil.

What happens when children are excluded

This is the second edition of the book. The first edition was published in 2009. Sadly, figures from 2022 show that little has changed in the intervening 13 years. Numbers of children in Pupil Referral Units have increased from 13,240 to 15,396. This might be because schools use temporary placements as an alternative to exclusion. However, schools also have many other ways to exclude a learner.

Exclusion can mean attending part-time and being in another setting for the rest of the school week. It can mean being in a separate part of the school from the rest of the class, being on a reduced timetable or being offered a managed move where professionals encourage children and their parents to consider another setting or education at home.

Competing agendas

Pupils may also be off-rolled, which is defined by Ofsted as ‘removing a child from the school roll when it is in the best interests of the school rather than the best interests of the pupil.’ The number of children off-rolled is unknown. While there is much talk of reintegration, or integration into a different setting, this only works when staff and society engage with young people and their families.

Solomon also looks at the impact on staff who work with children who are in danger of being excluded. Staff groups in exclusion zones may themselves come to feel separate and segregated. ‘This leaves such staff caught in a dilemma as to whether to feel devalued and ignored by the mainstream, or to speak out and risk being seen as troublesome and challenging (again just like the excluded children themselves).’

A perspective from critical race theory

George Floyd’s murder became the catalyst for organisations to examine their practices from an anti-racist perspective. Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people. Black people are more likely to be homeless, living in poverty, and to have worse job prospects and poorer health. Black boys are overrepresented in PRUs.

Schools need to guard against unconscious bias. Boyd argues that staff should have a checklist that they work through before choosing any form of exclusion, as ‘one way to tackle unconscious bias is to create processes and procedures which means individuals have to think carefully before acting’.

‘Perhaps in time there will not be a disproportionate exclusion of Black people,’ says Boyd. ‘Equality can and must be realised.’

Alternative solutions and success stories

Fiona Blyth and Richard Lewis talk about systems-psychodynamics that help staff develop consistent approaches and form positive relationships. Their analysis covers many areas, including:

- Shared core values, goals, approach and language

- Interactions with parents and families – helping them to feel heard, understood and involved

- Having an educational psychologist who knows the staff and pupils

- A whole-school approach to attachment and trauma

- Prioritising pupils’ involvement

Many settings would agree with this list. In addition, the researchers found some exemplary practice that had a lasting impact. They described settings where staff went ‘above and beyond’, providing ‘unique and individualised support’ to the individual even after they had left the setting. Everyone worked together so that EPs provided supervision for staff and staff provided assistance to families.

These centres often adopted a strengths-based approach, always looking for the positives and maintaining a friendly, family-like environment. They also engaged young people in discussions about what future success would look like and helped them to plan for the next steps in education and training. Children came to feel that they were not a problem, that they did not need to be contained and constrained but instead that they were moving forwards in their lives and that they had a team behind them.

The five case studies

These give readers the chance to apply the theoretical models to real children and to learn about their journey from school to exclusion, looking at the factors that have impacted their attitudes and behaviour.

| The child | The exclusion | Observations from others |

| Letitia – mixed race In supportive single-parent family | Managed move Exclusion from second school; good relationship with mentor | ‘Schools … have to look very carefully in the future at providing almost individual timetables for a small number of students who have needs which are different from others.’ Authors |

| Chip – white male Family poverty, threat of eviction, debts | Excluded at the end of Year 6 Started secondary school; disruptive, attended ‘in-school’ unit Excluded and, after a long period, is doing well in a PRU Talk of sending him back into mainstream | ‘if he is stable for once in his life, why push him back … into the system to fail again?’ PRU manager |

| Jack – mixed race Protective of mother, bad relationship with father Domestic violence Father has now left the family home | Difficulties in primary school Behaviour strategies were of limited success Out of school for five months Managed move to a PRU Return to secondary | ‘You do an awful lot of social work both for parents and for the children… We’re getting better at it but I do feel a lot of it is reactive and just containment as opposed to spotting the problem earlier on and putting in the right people at the right time to deal with it.’ Headteacher of excluding school |

| David – white male Very supportive mother who asked for autism assessment | Difficulties in primary school Two periods in PRUs Excluded in Year 9 Now has statement for communication difficulties About to start FE | ‘If David was with us now, he wouldn’t have been permanently excluded. He would have gone into the nurture group … we could have had a much tighter package around him to prevent what happened.’ Senco, excluding school |

| Sam – dual heritage Parents separated Fond of both parents | Excluded in Year 8 after rewards and sanctions became less effective; ‘disengaged’ Attended a PRU for rest of KS3 and another PRU for the whole of KS4 Poor attendance Has a mentor | ‘He does talk quite normal and then he just decides that’s enough and goes off on one. Starts shouting … mum’s tried, dad’s tried. All the agencies have tried. There’s only one person who hasn’t and that’s Sam.’ Mentor |

Schools and services struggling

Time and again, the authors and parents talk about the unwieldy structure of schools; how one person makes promises and yet they will not be the ones who have to deliver. Parents complain about lost paperwork and delays, while schools talk about a lack of resources and support. One headteacher observed: ‘At that time we did not have the Youth Inclusion Support Programme run by the Youth Offending Team … we’ve used it since with two other children and it actually helped them turn their behaviour around.’

Families are left with little dignity

Schools and other agencies ask for and obtain a lot of confidential information about the excluded child and their family. Certainly, the family unit is put under the microscope. This is intrusive and it is not clear how the information is used, other than to pigeonhole the child and reinforce stereotypes about single-parent families, Afro Caribbeans and recipients of benefits.

The authors note that: ‘All the schools mention family circumstances as a factor in the pupil’s difficulties but none go on to say how they either took account of these circumstances in dealing with the pupil or how they took active steps to support the family. The difficulties are mentioned by way of explaining the problems but overall, there is a rather defeatist feeling that the family circumstances are so overwhelmingly adverse that there is little that can be done to change things.’

Schools are too big

Individuals who struggle can get lost in the system. Staff in secondary schools don’t know pupils as well as they do in smaller primary schools. A mother commented: ‘One of the things I have sort of notice is that the schools are very big now, I mean, you know, a thousand and odd pupils, it’s not like years ago when you had small schools with smaller numbers. I know it’s difficult to manage a large school, it’s difficult to hone in on an individual … But that’s no good to the child, is it? The fact that they are in a large school, people haven’t got time, it is not good enough, I don’t think.’

PRUs can offer a more personalised approach

Schools cater for large numbers and have rules and routines that apply to everyone. On the other hand, PRUs can start from where the learner is and adjust timetables and expectations accordingly. They don’t just work on the curriculum; they also focus on behaviour. They try to uncover the causes of a child’s responses and help them with self-regulation.

‘He wasn’t in a social group with other pupils,’ David’s PRU manager remarked. ‘He was on a one to one basis. We set about teaching the basic core subjects, maths, English, what he liked, and trying to engage in through that. It soon became apparent that David wasn’t the person that was described in the file. He took everything literally and there were certain people he could work with and there were certain people that he couldn’t … As we did various things, we realised one of David’s difficulties was the flight and fight scenario … We learned to recognise the warning signals and we would back off.’

How does exclusion impact children’s futures?

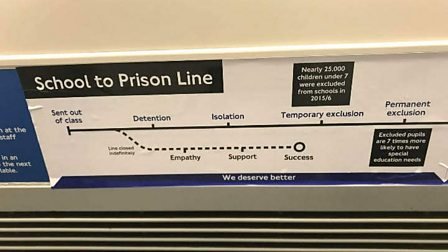

It seems fitting to let learners have the final word. In August 2018, on GCSE results day, a group of students called ‘Education not Exclusion’ highlighted the plight of children who are excluded from school through adverts on the London Underground, releasing the following statement:

‘While most pupils across the country are excitedly awaiting news about their future, thousands remain left behind. Every day, 35 students (a full classroom) are permanently excluded from school. Only one percent of them will go on to get the five good GCSEs they need to succeed. It is the most disadvantaged children who are disproportionately punished by the system. We deserve better.’

You can find ‘Excluded from School’ using the TeachingTImes Bookshop link below.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month