Socio-economic status, parenting styles, community and social networks, quality of health, fluency in the vernacular language are just some of these factors. But once children enter day-care or start at school there are a range of other ways in which children can be helped to succeed, especially those who are more vulnerable. Two of the best repositories of evidence about the mechanisms by which social mobility can be achieved through education are The Sutton Trust1 and the Education Endowment Foundation2.

Within schools there are many ways in which teachers can make it more likely that children will thrive, regardless of background. Early intervention is well known to be important but a recent review Ofsted concluded that, while there is little doubt that early education for low income and ethnic minority children can combat educational disadvantage, ‘the design of programmes and the approach to pedagogy and curriculum is crucial to success.’3

Achievement for All has identified promising practices which go further in identifying the approaches to leadership and teaching and learning which help, as well as the kinds of structured conversations with parents and carers which are useful4. And clearly the quality of teaching matters enormously as many researchers have shown, with John Hattie having arguably done more than most in making more specific data available, accessible and useful5.

From time to time the nature versus nurture dilemma raises its head along the lines of success being dependent on intelligence. But there is mounting evidence that, while genetic inheritance of course matters, there are many things that teachers and parents can do to help all children succeed and, effectively, become more intelligent6. Angela Duckworth and Martin Seligman have, for example, shown how something like self-discipline is a much better predictor of success in later life than IQ7.

Capabilities and character matter

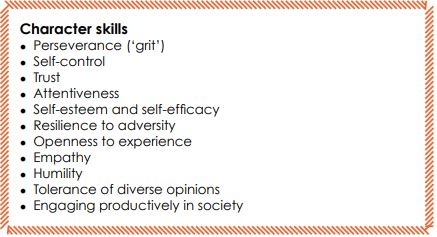

Indeed it turns out that there are many attributes like self-discipline which matter both at school and in later life. Nobel Laureate James Heckman and his colleague Tim Kautz at the University of Chicago have identified a set of skills that are generally valued across all societies and culture8, see Table 1.

Increasingly capabilities or attributes such as self-discipline, perseverance and resilience are referred to as a part of a bigger concept – character. In the last decade the Character Education Partnership9 in the USA has been influential in introducing the idea of ‘performance character’10 as a way of describing the kinds of attributes which correlate with academic success. In the UK the Character Inquiry11 initiated by Demos invited government and other stakeholders to consider the importance of developing character across the nation both in and beyond school, while the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues at the University of Birmingham12 has helpfully built further on all of these ideas.