Difficulties in identifying good practice approaches to the deployment of teaching assistants (TAs) are nothing new. Ever since the Sutton Trust and Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS) reports first surfaced between 2008 and 20121,2, the value and place of TAs in our schools has been continually questioned. The assertion that many TAs are having a neutral and, in some cases, a negative influence on pupil attainment is significant cause for concern. Clearly, the government is unsure of their stance on TAs, choosing not to publish the long awaited new TA standards and instead leaving it to the unions to take the plunge.3

Why the concern?

Uncertainty around the role of TAs is entirely justified when we consider the widespread problematic nature of their current deployment. For a start, it is widely acknowledged that TAs spend the majority of their working day supporting children identified with special educational needs (SEN), or those struggling to access the learning in the main classroom. Consequently, we often have a situation in which the most vulnerable and arguably most ‘challenging to teach’ children are spending a large proportion of their time with the lowest qualified adults in a classroom. It is, therefore, not a surprise that this scenario isn’t always having positive results in terms of pupils’ academic progress.

When we also consider that there are significant difficulties with TAs’ management across our schools, with staff in different positions holding the responsibility for managing TAs, and the dearth of relevant training opportunities available for TAs, the severity of the problem becomes clear. The roles that TAs undertake on a daily basis are hugely varied and the level of skills, knowledge and experience that TAs bring to those roles are more varied still. Therefore, a ‘one size fits all’ approach isn’t appropriate.

There are over 200,000 TAs in English primary schools alone and, as a workforce, they cost the government in excess of £4 billion a year. Consequently, many of the aforementioned difficulties associated with their role are positioning TAs as an easy target for cuts. Some Local Authorities have announced significant cuts to TAs’ wages in recent weeks. Durham’s decision to reduce TAs’ pay by up to 23 per cent will have a huge influence on the workforce, especially when we take into account that the average TA in Durham currently earns around £15,000 a year.

Yet, many large scale research studies, including my own recently completed doctoral study into the role of TAs, have highlighted that schools overwhelmingly deem TAs to be indispensable in the smooth running of school life. So, where does their value lie, and how can we make the case for their continued employment?

How should TAs be used?

The Education Endowment Foundation published a report in Spring 2015 which, for the first time in recent years, attempted to highlight effective practical approaches to the deployment of TAs in our schools.4 Approaches such as ‘use TAs to add value to what teachers do, not replace them’ were an important step forward, yet, in many cases would involve a significant organisational shift if they were to be implemented well.

The focus on quality intervention programmes was also an important recommendation and, again, would require a shift in approach for many schools when choosing the programmes that TAs implement. For me, shifting the way in which intervention programmes are selected is one of the most important and successful ways that many schools can improve pupil outcomes and make best use of the skills of TAs.

Many TAs spend a significant proportion of their day supporting small groups of children, often in a space away from the main classroom, implementing intervention programmes. These programmes most often focus on building skills associated with maths, reading and/or writing. We know that intervention programmes based on evidence and research are far more likely to promote pupil progress. However, we also know that many schools understandably select intervention programmes based upon word of mouth, clever marketing campaigns and/or how well they fit the needs of their children at that time. These methods of selection do not always take into account the level of evidence that a programme is able to demonstrate and, therefore, may not result in the levels of pupil progress that schools would like.

Additionally, the strong focus on maths, reading and writing in the intervention programmes selected often puts significant pressure on TAs to essentially ‘teach’ some of the most vulnerable children in our schools many of the basic skills associated with mastering core subjects. Unless TAs are given relevant and in-depth training on how to implement these programmes, it is likely that many TAs will not possess the level of knowledge and/or skills to implement these programmes effectively. This is contributing to findings such as those in the Sutton Trust report5—that many TAs are not having positive influences on pupil attainment.

Of course, there is the argument that we shouldn’t be asking TAs to ‘teach’ children the core skills associated with reading, writing and maths in the first place. Many do not have the same level of skill or qualifications as teachers (nor should they) and, crucially, they are not paid to take on that role. Additionally, we are often asking them to take on this role with some of the most vulnerable children in schools. If we expect TAs to work essentially as ‘substitute teachers’, then we need to professionalise them, which would necessarily involve improving the status of the role through increasing minimum levels of qualifications and increasing pay.

We would also need to make the transition pathway from TA to teacher much easier, for those who do possess ‘substitute teacher’ skills. Asking TAs to undertake a foundation degree, then a full degree, then a PGCE simply takes too long and doesn’t take into account their existing skills in working with children. Since it is unlikely that the Department for Education will agree to this anytime soon, we need to rethink the way in which we conceptualise their role.

My research highlighted a significant and often under-appreciated aspect of TAs’ role that may engender a reconceptualisation of how we view their influence. This role relates to TAs’ influence on pupils’ social inclusion, and is illustrated in the short case study below.

Case study: Social-skill-focused interventions

This one-form-entry primary school in Greenwich had a large staff body, comprising approximately 20 TAs. A TA was present in every main classroom at all times, and additional TAs used spaces around the school to work with small groups of children throughout the day.

The school had worked hard to support TAs in identifying their areas of interest and responded by providing opportunities for them to upskill and specialise in those areas. For example, one higher level teaching assistant (HLTA) specialised in supporting gifted and talented Year 6 pupils in maths; another TA worked with boys in Year 4 who were struggling with reading. Crucially, the school gave TAs appropriate training and professional development experiences to ensure the quality of these intervention groups.

One TA, Gina, had a particular interest in social inclusion and building social skills with pupils. Gina was present at all major periods of the day in which social interaction between peers took place—for example, on the playground before school, at break time, during lunch time and at the end of the day. This meant that she had a very strong understanding of the social networks at play in the school; she understood which ‘group’ each child was a part of and could identify those who had not developed the age-appropriate social skills to be able to participate with their peers. Gina then targeted those children with her evidence-based intervention sessions—for example, LEGO therapy sessions, time in the school’s sensory room, or circle time sessions.

Through their basis in peer-to-peer interaction, these sessions supported pupils to build social networks. They also helped pupils to develop the age-appropriate social skills to be able to participate in whole-class teaching back in their classroom. For example, Gina taught them how to ask and answer questions effectively, and how to manage their feelings appropriately. She also supported them to develop self-awareness around their existing abilities.

The case study above highlights the impact a focus on social inclusion can have on the role of TAs and pupils’ educational experiences. We know that if children are happy and feel able to participate in their learning, then their academic attainment will improve. We also know that unless children possess a basic level of social competence, they will find participation difficult. Therefore, using the strong pastoral role that TAs often undertake with the pupils they work with can be a positive way to ensure TAs’ influence is appreciated.

The relationships that some children build with TAs are often stronger and deeper than those built with their class teachers, due to the time intensive rapport. We should be doing more to use this rapport in the way in which we deploy TAs. This also avoids a situation where we expect TAs to take on a ‘substitute teacher’ role with the most vulnerable students in reading, writing and maths.

To illustrate this further, the case study below highlights another specific approach to using one TA’s strong pastoral relationship with a child in the school.

Case study: Happy book

Sarah was a TA I observed during my time at this two-form-entry primary school in Wolverhampton. She led a weekly half-hour session with Paul, a boy in Year 4, who experienced mental health difficulties and had been diagnosed with depression. Paul had recently been experiencing negative thoughts relating to his self-esteem and had frequently discussed feeling worthless. The sessions supported Paul to achieve his Individual Education Plan (IEP) target of ‘Paul can identify at least three positive things about himself when asked.’

The sessions involved Sarah encouraging Paul to complete his ‘happy book’. He was asked by Sarah to think about three things that had happened to him over the course of the previous week which had made him feel happy. When he’d chosen them, he would write descriptions of the events in his book, without showing Sarah, and then tell her the stories that resulted in his feeling happy.

Sarah had bought ‘special pens’ for him to use in these sessions, including glitter pens and coloured pencils which Paul thoroughly enjoyed using and which other children in the school were not permitted to use. The personalised nature of this intervention was hugely successful in encouraging Paul to share his experiences with Sarah, and it was obvious that he very much enjoyed the one-to-one time that he spent with her.

Their dialogue also revealed that Sarah knew his family well, asking about his parents and sister frequently, and understanding a significant amount about their family dynamic. This indicated that Paul and Sarah had built up a culture of mutual trust and respect, indicative of a strong pastoral relationship between the pair. It also indicated that Sarah had good links with the wider school community, which she was using to enhance her role in school.

Although the impact of these sessions on Paul’s academic attainment could not be identified, it was obvious from interviews with teachers that Paul’s confidence had grown from his time with Sarah and that he came back to class better prepared to learn after these sessions.

Of course, as I mentioned before, a ‘one size fits all’ approach is not appropriate for the TA role. It would be inefficient to have TAs deployed to implement social-skill-focused intervention programmes with all children they work with. However, for some TAs, this is a positive deployment approach. It would make better use of many TAs’ existing skills and knowledge, and better position children to access the high quality teaching of a teacher in their main classroom.

For those intervention programmes focused on reading, writing and maths, schools ensuring that high-quality, evidence-based programmes are selected is key to their success. Additionally, providing specific, relevant training for TAs on how to implement these programmes will also improve their influence on pupils’ learning.

The need for effective training

The findings from my doctoral study highlighted that there are many exceptional TAs who have built up extensive knowledge, skills and expertise over time. Yet, the most effective TAs that I worked with had been in the job ten years plus. We can’t wait that long to reach optimal efficacy. Therefore, many schools need to commit more of their budget to providing professional development and training opportunities for these staff members.

Having researched available training opportunities as part of my doctoral study, it quickly became apparent that there is a severe dearth in opportunities that are specific to the role of TAs and relevant to their everyday responsibilities. It is, therefore, not surprising that schools commit a very small amount of their budget to TA training. I decided to utilise the findings from my doctoral study and set up Inclusive Classrooms, which is the first organisation working across the UK to provide on-the-job training opportunities exclusively focused on the role of TAs in mainstream primary schools.

Our flagship programme, Social Storytime, makes use of TAs’ pastoral role by providing an evidence-based three-term intervention programme, supporting pupils to build age-appropriate social skills and participate in their learning. The 60 pupils who have benefited from our programme to date have improved their social skills by an average of 24.95 sub-levels on our skills-wheel impact-measurement tool, which is 20.79 per cent. There are also early indications that the programme accelerates academic attainment—the pupils of one school made on average 2.6 sub-levels more progress throughout the academic year when compared to a control group in maths.

For TAs, the programme has been a huge success—they have accessed development opportunities that interest them, are within their professional capabilities, are reasonable in expectation, and allow them to take responsibility for the learning experiences of the children involved during the intervention, including ownership over the assessment tool.

Who’s in charge?

In order to provide these positive training experiences and support TAs in better utilising their existing skills, effective management systems are key. However, as I alluded to earlier, there is widespread recognition that TAs’ management systems are often confusing at individual school level and inconsistent on a national level. Many studies have identified that TAs are often unaware of who their line manager is, whether they have more than one manager, or indeed who has overall responsibility for their work. This is particularly prevalent in primary schools. Headteachers, deputy heads, special educational needs coordinators (SENCOs), inclusion managers, class teachers, HLTAs and TAs themselves have all been named in different schools as responsible for TA management.

Many of these management difficulties emerge, for me, from a tension between policy and practice. At policy level, it is important to design documents and approaches which set out consistent expectations of TAs and support coherence in the activities undertaken within their roles. At practice level, flexibility is vital in order to respond to both pupils’ and TAs’ changing needs and the ever-changing school day. A balance needs to be struck here between clear, manageable role descriptors and flexibility, which is not easy to achieve.

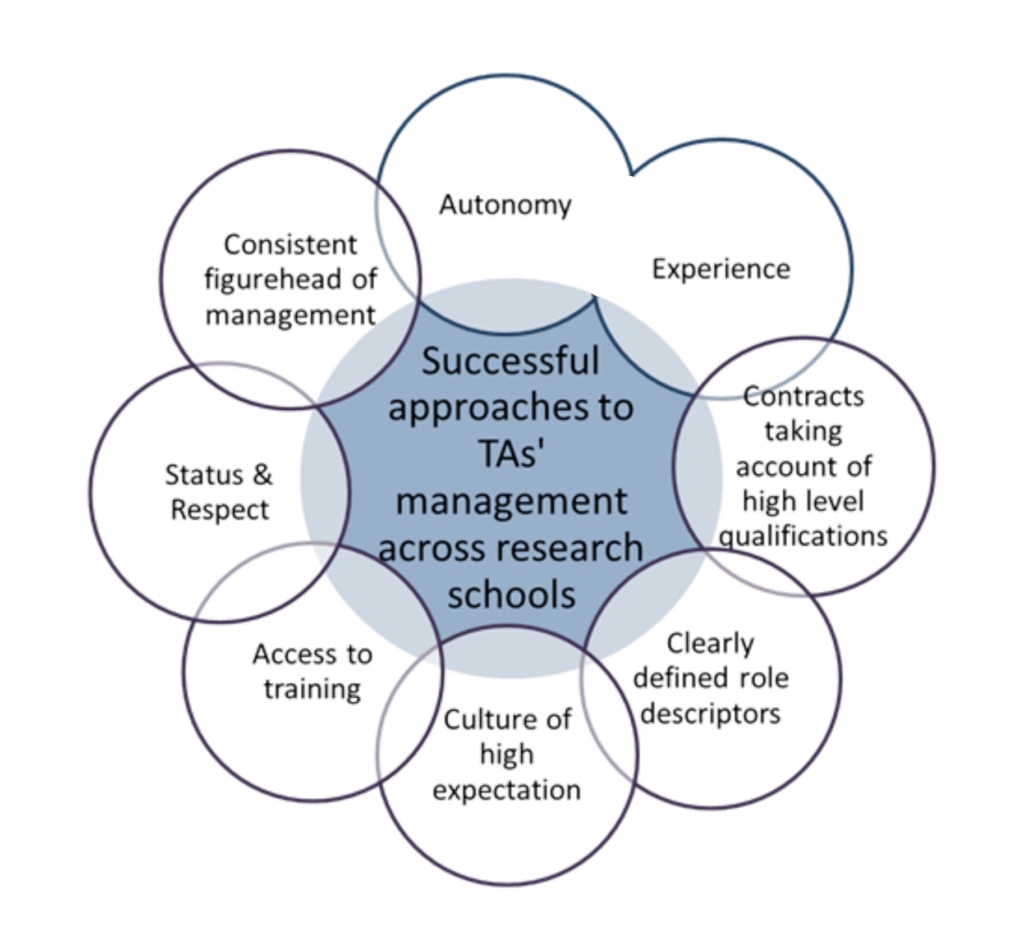

My doctoral study indicated some potential successful approaches to TAs’ management across the three primary schools in which I conducted research. These approaches are depicted in figure 1.

As was previously discussed, access to training seems vital in both promoting best use of TAs’ existing skills and in providing opportunities to upskill. Additionally, highlighting a consistent figurehead of management, who promotes a culture of high expectation and really values TAs’ influence on pupils’ learning, will help avoid many of the current confusions around management responsibilities relating to TAs. This will also help with promoting high levels of job satisfaction among TAs and will ensure that the wider staff body really respects the work that they do.

Interestingly, where TAs were given the autonomy to plan, assess or implement programmes of work independently, better levels of job satisfaction were seen and they felt that their skills were better used. There is therefore a tension between appropriate levels of expectation in terms of TAs avoiding taking on a ‘substitute teacher’ role and supporting independent working. Yet, this positive view of autonomy was only seen when TAs had been in the role for a while, over ten years or so. When TAs were relatively new to the role, their levels of confidence were lower, and this meant that the idea of taking on whole classes or planning and assessing independently was often not viewed positively.

Prove your TAs are worth it!

The debates surrounding effective conceptualisations of the TA role will continue, as will the struggle to articulate TAs’ positive influence on pupils’ education. However, schools can support these debates by ensuring that all intervention programmes they ask TAs to implement are grounded in evidence and that they fit TAs’ skills, knowledge and interests. Additionally, it is vital that TAs have better access to training and good quality management to support effective implementation of these programmes.

Finally, appreciating the opportunity for TAs’ pastoral role in supporting pupils to develop the social skills to actively participate in their learning is an important step forward.

Dr Helen Saddler is the Director and Founder of Inclusive Classrooms. In 2016, she completed her PhD in Education at the University of York. This in-depth study into the role of TAs has formed the basis of the programmes offered by Inclusive Classrooms.

References

1. Higgins, S., Kokotsaki, D., and Coe, R. (2011) Toolkit of strategies to improve learning. Summary for schools spending the pupil premium. [pdf] Available at: dro.dur.ac.uk/11453/3/11453S.pdf?DDD45+DDD29+DDO128+ded4ss+cqjd36 [Accessed 10 October 2016].

2. Blatchford, P., Bassett, P., Brown, P., Marin, C., Russell, A. and Webster, R. (2008) Deployment and impact of support staff in schools and the impact of the national agreement. [pdf] Available at: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http:/www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/DCSF-RR027.pdf [Accessed 10 October 2016].

3. NAHT (2016) Professional standards for teaching assistants. [pdf] Available at: naht.org.uk/welcome/news-and-media/key-topics/staff-management/professional-standards-for-teaching-assistants-published/ [Accessed 10 October 2016].

4. Education Endowment Foundation (2015) Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS): Evaluation report and executive summary. [pdf] Available at: v1.educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/uploads/pdf/PATHS.pdf [Accessed 10 October 2016].

5. Higgins, S., Kokotsaki, D., and Coe, R. (2011) Op cit.