I’ve taught in classrooms and labs without windows, with immovable yet broken demo benches, and without environmental controls of any kind. I’ve planned lessons in make-shift “desks” supported by milk crates in three different US cities. Since my teaching days, I have worked inside over 1000 classrooms in schools internationally, most of which sorely needed either a complete overhaul or significant improvements to make the space truly functional. Teaching and learning are two of the most difficult yet important jobs on the planet, and people engaged in both deserve comfortable, safe, clean, beautiful places to do their work. I commend the current trend of facilities upgrades, renewals, and new builds on school campuses.

The transition to modern learning spaces has embraced more than cosmetic or functional upgrades. Many school boards, leaders and teachers are taking this opportunity to upend traditional teaching and learning behaviors as well. Modern learning spaces and 21st century teaching and learning go hand in hand, right? Only when schools intentionally integrate both processes and players to allow learning to guide space redesign.

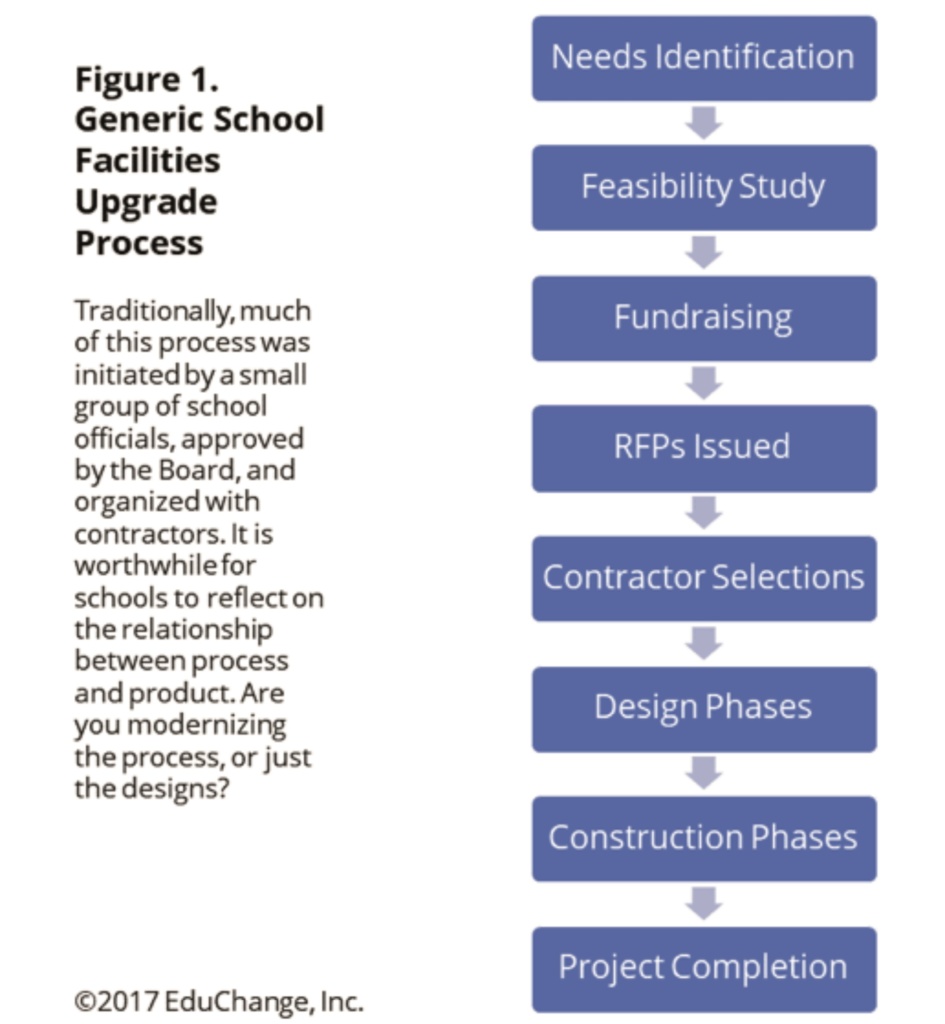

In the past, school facilities projects were responses to common, tangible needs: the need to increase square footage to accommodate more student seats; the need to update antiquated facilities to improve community perceptions or increase enrollment; the need to fix plumbing issues or a collapsing roof, etc. Such decisions required a small group of school or district leaders to scope the project, often with the help of outside professionals who conducted a feasibility study. Monies were raised through funding drives or a local bond and, once secured, an RFP was issued for more detailed proposals. The bidding process yielded a selection of contractors, planning and construction timelines were established, and the rest of the school community was alerted to the pending changes (Figure 1).

The new wave of school construction has introduced at least two new variables to the process: 1) a new set of voices who influence project scoping at an early stage, and 2) an aspirational vision for modernized teaching and learning that educational leaders, teachers and students can barely envision. Adding two variables to any process can be problematic, but their inherent contradiction makes matters worse.

On one hand, there is a democratic desire to involve the people who will inhabit these modern learning spaces. This would make sense, except that teachers and students are not being asked to imagine design elements that would make their current work easier or more effective. The aspirational vision complicates the request: Don’t imagine a better place to engage in your current practices; instead, imagine and design physical requirements for practices you have not yet tried, using tools you have not been trained to use properly.

Well-intentioned school and district leaders want total transformation: project-based, tech-enhanced, creativity-fostering teaching and learning—with brand new spaces to showcase all of it. But their community messaging often focuses on the expensive new construction, mainly because that requires a major fundraising campaign. You may be surprised how many leaders simply add teacher representatives to design teams, and then casually state during a faculty meeting, “And our new spaces will allow for 21st century teaching and learning,” as if that is going to be as easy as hanging a banner in the front foyer.