To stem the decline in languages teaching in maintained secondary schools in England the Department for Education established The National Centre for Language Pedagogy (NCELP) as a research led programme, co-managed by The University of York and The Cam Academy Trust. It works in partnership with university researchers, teacher educators and expert practitioners, and with 18 Specialist Teachers in nine Leading Schools across the country acting as language hubs, to improve language curriculum design and pedagogy.

TeachingTimes:

Can you explain the context around the NCELP coming into being, and what are its philosophy and objectives?

Joe Fincham:

The context is, of course, the dramatic decline in Modern Languages in this country over the last decade or more. Teachingtimes illustrated the downward spiral of teaching and take-up in Modern Languages in its recent article on the huge languages skills deficit in the UK.

The British Council’s survey ‘Language Trends 2020’ reveals fewer and fewer pupils studying Modern Languages at KS4 and except for Spanish the number of GCSE and A Level exam entries for French and German has been in free fall.

In 2016, only 34% of all pupils at the end of key stage 4 achieved an EBacc language GCSE at A*-C grade and only 49% entered a language GCSE.

There is a danger that if we do not reverse this decline, the country will not be able to produce the qualified home-grown graduate teachers to teach modern languages to the future generations of children.

Research has shown that the deficit in language skills is costing the UK an estimated 3.5% of economic performance. This is huge. Billions are being lost to the economy.

NCELP was born out of the influential ‘Modern Languages Pedagogy Review’ undertaken in 2016 by the Teaching Schools Council. It was chaired by Ian Bauckham, a former headteacher and linguist, who is now interim Chair of OFQUAL. NCELP is developing and piloting a new languages strategy for England based on the review’s key recommendations.

In the first instance, NCELP’s core strategy objective is to increase take-up and achievement in GCSE Modern Languages by revolutionising the Key Stage 3 schemes of work in in French, Spanish and German and ensuring success through carefully planned sequencing and progression of learning. Supported by its 9 lead or hub schools across the country, NCELP is underpinning its campaign with a vast array of free resources, initially for Year 7 and Year 8.

TeachingTimes:

Why do you think NCELP stands a chance of reversing the steep decline in language learning in our schools? How different are the schemes of work?

Joe Fincham:

Because NCELP is research led and pedagogy driven. It goes beyond the moral or ‘good education’ arguments for learning languages, although. of course, these remain valid. The essential element is proven, effective pedagogy.

Gone are topic driven schemes of work and the chaotic presentation of random grammar and vocabulary to support the delivery of the topic language.

The new priority consists of carefully planned, short but connected sequences of learning in phonics, grammar and vocabulary. These are constantly reinforced and assessed so that pupils can map their own progress and feel they are learning successfully. The content is presented and practiced in a format which allows essential knowledge to be acquired and consolidated sequentially. There is a conscious effort to remove barriers to successful learning.

TeachingTimes:

Can you illustrate this?

Joe Fincham:

Where possible, the bewildering complexity of irregularity is removed for young learners.

Everyone who has ever learnt a language knows that the correct use of verbs is often the biggest challenge. For example, in the Yr 7 French Scheme of Work pupils are asked to recognize and learn, through practice and planned ‘revisiting’, the most frequently used verbs in the language so that they can begin to create their own language as quickly as possible.

So, in the first months of learning French, children are introduced to 1st, 2nd and 3rd singular form of être, avoir, aller, faire.

They do not have to learn or use the whole paradigm of the present tense at once, but rather begin with the most commonly used forms of the verb e.g. ‘je’ and ‘tu’. This avoids too much cognitive load for learners and enables them to quickly and easily equip themselves with knowledge and skills that can immediately be used in conversation.

Target language is encouraged in the classroom, but not if it hinders learning. So we use the first or main school language of the child to explain phonic and grammatical patterns as well as new vocabulary items and to model tasks. ‘Classroom language’ is taught as part of the weekly vocabulary for students and is introduced gradually across the scheme of work and then adopted in the classroom by the teacher as and when the vocabulary is taught.

A good illustration of what we do not do is to begin the Yr 7 SoW with the dialogue ‘Comment t’appelles-tu? Je m’appelle…’ A child might be able to rote learn this but is very unlikely to understand and be able to replicate the grammatical complexity of inverted question forms and reflexive pronouns. The pedagogy is all wrong there. We prefer to teach ‘Je suis (name)’ or ‘Mon nom est (name)’ because the language is much more accessible and easily transferable.

TeachingTimes:

And what about vocabulary? How does that fit into the schemes of work?

Joe Fincham:

Pupils are asked to learn a minimum of ten words per week or 5-10 words per lesson. Lexical items to be learnt are chosen because they are high frequency ‘source’ words and they can reinforce phonic and grammatical patterns.

So clearly the French verb ‘ÊTRE’ (to be) which has a lexical frequency ranking of 5 attracts a greater teaching focus than ‘POULET’ which has a ranking of 4222!

If children learn a minimum of 10 Spanish words a week for 36 school weeks a year from Year 7 to Year 11, they will have learnt the number of words on the current AQA Spanish Higher Minimal Core Vocabulary list.

We should remember that the expected size of vocabulary to achieve a top GCSE grade and commence with confidence an A Level modern language course is 2000.

Research informed practice has shaped the NCELP tack on vocabulary learning. Core to its strategy is the knowledge that if we do not teach vocabulary by frequency of occurrence, with special attention to common verbs, it will result in pupils quickly realising that they cannot say or comprehend basic things in the target language.

TeachingTimes:

My primary aged grandchildren are bombarded with concepts such as graphemes, phonemes and frontal adverbials. I imagine the phonic and grammar skills that children have picked up in the KS1 and KS2 National Curriculum for English equip them well for the NCELP approach to Modern Languages learning in KS3. Is that correct?

Joe Fincham:

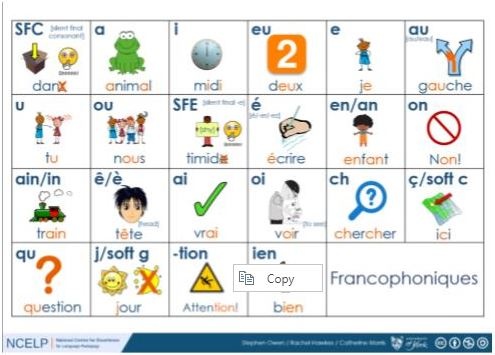

Yes, exactly. The NCELP tactic is indeed to harness the power of that KS1 and KS2 learning in English to make sense of the code of a new modern language.

The practice and acquisition of short, sequenced packets of phonics allows them to begin to understand the sound and spelling systems in the target language.

The carefully ordered teaching of high-frequency grammar elements and varied sets of vocabulary allows children to become confident with regular, transferable, linguistic patterns.

In this way, from an early stage, children can begin to decode simple spoken and written language. By transferring simple phonic and grammatical patterns that they have learnt they can start to construct their

own language with the vocabulary they have learnt. Children find this early achievement very motivating and of course success motivates.

We must remember that it is impossible for our pupils to learn a target modern language implicitly as if they were learning their first language or if they were immersed in the target language which is all around them. Our approach encourages linguistic deductive skills that are carefully orchestrated by the schemes of work and the teacher.

The target language learning must be manageable in the small amount of time allotted to it in the curriculum. The children need to be carefully guided to make sense of the new language and progress.

TeachingTimes:

How does the NCELP Key Stage 3 strategy marry up with modern languages teaching in primary schools where the subject is part of the statutory curriculum? What lessons are there for successful primary/secondary transition?

Joe Fincham:

This is a hot topic. Large scale research has revealed that the benefits of modern languages teaching in primary school are not as big as we might be instinctively inclined to believe or hope for.

In short, the science indicates that children who learn a new modern language in primary school do not achieve better at the end of secondary school than pupils whose instruction begins later.

Of course, there is an infinite interplay of variables that affect the quality and provision of modern languages in primary schools and the ability of secondary schools to organize effective transition that builds on prior subject learning. The latter compounds the former.

NCELP believes that long term benefits for primary modern languages could be felt if there were clear goal posts for the end of primary such as an agreed list of 300 or 400 words and agreed programme of phonics, which could be the basis of transition arrangements to secondary.

The inclusion of some explicit language analysis in primary modern language learning would also be welcome in order to aid the learning of other languages at secondary level.

TeachingTimes:

What would you recommend in the short term in this crucial area?

Joe Fincham:

In the short term, our hope is that primary schools could furnish receiving secondary schools with a profile of what the Yr. 6 children should know and be able to do at as they transfer to secondary.

Our main recommendation is that secondary schools teach the NCELP Yr. 7 scheme of work, because it will revisit or introduce essential language, it will not repeat familiar topics and it will reduce the possibility of de-motivation through boredom or excessive challenge.

The advice is that secondary schools do some baseline testing. At Blatchington Mill, together with some of primary feeder schools, we aim to use the ‘Primary Bee’ to contribute to our baseline assessments and ascertain prior MFL knowledge and skills.

NCELP has already done a lot of work around primary/secondary transition, recommending other assessment tools such as the EU’s ‘The Language Magician’ and demonstrating models of modern language learning aptitude tests.

TeachingTimes:

How did Blatchington Mill become one of the 9 NCELP hub or lead schools? What does your school do to support other schools in your area?

Joe Fincham:

Our school leadership group strives to be at the forefront of innovation and best practice. So we applied as we felt that Blatchington Mill met many of the NCELP criteria. We had a strong uptake of pupils studying GCSEs in Yr 10 and our numbers were improving over a three-year period.

Pupils entitled to Pupil Premium Funding were making particularly good progress in modern languages by the end of KS4. We could also show that we were already applying many of the principles highlighted in the 2016 MFL Pedagogical Review.

We reach out to partner schools through the Pavilion and Downs Teaching Alliance which has appointed me as Specialist Leader in Education for Modern Languages. We organize Hub Days of concentrated CPD and we deliver NCELP training in partner schools. There is of course national collaboration between the 9 NCELP Lead Schools across the country so that we can calibrate our practice.

We provide support to local schools that have expressed a distinct interest in improving uptake in GCSE modern languages. And, naturally, we work closely with our main primary feeder schools through outreach and direct specialist teaching to support primary-secondary transition in modern languages.

We aim to forge closer training relationships with local authorities and regional ITT providers in the future.

TeachingTimes:

Modern Language teachers have been claiming for years that, in particular, the GCSE French and German exams are unfair because candidates find it harder to achieve higher grades at GCSE in these subjects. Schools and students have voted with their feet. Are you optimistic that the forthcoming subject content review of GCSE Modern Languages exams will reflect and indeed promote the NCELP schemes of work?

Joe Fincham:

Yes, I am optimistic. The NCELP schemes of work are in full alignment with the National Curriculum programmes of study and the new OFSTED Framework.

In November 2019, the Government finally conceded that there was sufficient research evidence to show that indeed French and German GCSEs were ‘consistently harder’ than other subjects. It ordered grading adjustments to make French and German more accessible to pupils.

The Government then set up an independent panel of experts to carry out the ‘Review of Subject Content for GCSE Modern Foreign Languages’. The panel will be chaired by Ian Bauckham who, as you will recall, was Chair of the Teaching Schools Council MFL Pedagogy Review in 2016 that gave birth to NCELP.

The panel also includes Professor Emma Marsden, Dr Rachel Hawkes and David Shanks, all of whom are involved in the leadership of NCELP and the roll-out of its pedagogy and resources across the country.

I now see clear joined-up thinking at the highest levels to stem the decline in modern languages in our schools. Research informed pedagogy is the way forward not just for ML but for all subjects. I hope colleagues who care about modern languages teaching will inform themselves about NCELP and climb on board. The resources are excellent and free.

Simon Sharron is a former headteacher of a 3000 student European school in Brussels, operating in nine different languages, and a MFL specialist and adviser

Joe Fincham is head of Modern Languages at Blatchington Mill School in Hove, one of the 9 hub centres of the NCELP strategy

References

- DfE and NCELP, 2019 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-centre-for-excellence-to-boost-modern-foreign-language-skills

- NCELP, https://ncelp.org/

- MFL Pedagogy Review 2016, https://ncelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/MFL_Pedagogy_Review_Report_TSC_PUBLISHED_VERSION_Nov_2016_1_.pdf

- NCELP French SOW, https://resources.ncelp.org/concern/resources/3f462554x?locale=en

- Joe Fincham, Teaching GrammarMFL teaching aids: Asking effective questions - grammar building blocks (KS3) - BBC Teach MFL Subject Content Review 2019https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gcse-modern-foreign-languages-subject-content-review-panel/review-of-subject-content-for-gcse-modern-foreign-languages-independent-panel-members

- The Pavilion and Downs Teaching Alliance http://www.pavilionanddowns.co.uk/

- Primary Bee, Routes into Languages, https://www.routesintolanguages.ac.uk/events/primary-bee-registration

- The Language Magician, European Union Erasmus +, https://www.thelanguagemagician.net/

- MFL Subject Content Review, DfE 2019 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gcse-modern-foreign-languages-subject-content-review-panel/review-of-subject-content-for-gcse-modern-foreign-languages-independent-panel-members

- Inter-subject comparability, DfE 2019 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/inter-subject-comparability-in-gcse-modern-foreign-languages

- Rachel Hawkes and Emma Marsden, GCSE Subject Content for Languages 2021 TRG 3.2: GCSE Consultation // NCELP