Twenty-something pupils in a room, one evening after school, all talking about coding. Yes, coding, and solving problems. Hunched over their laptops, the light from the screens illuminating their faces and having fun. Fuelled by their own imagination and, OK, pizza and cola! Yes, this was our own hackathon and we were very proud of how well it was going.

A hackathon?

A hackathon is an event where programmers meet to solve a collaborative problem. Quite often at commercial hackathons, the theme is for participants to think up big problems to solve, such as problems with transport, the environment, or health or social issues. They then try to come up with winning app innovation ideas that tackle these problems.

At my school we wanted to do something much smaller and targeted, with an element of learning and challenge. How could we do it? At Wycombe Abbey we made the transition from IT to Computer Science early on and had been running GCSE and A level classes, although with small numbers. We realised we needed a fresh way to sell Computer Science to academic girls. We decided that the perceived ‘gender bias’ of girls not liking Computer Science was really a falsehood created by commerce in the 1980s. After reading Cordelia Fine’s Delusions of Gender, I realised that Computer Science could have a much more diverse appeal if we gave it some thought.1

We are fortunate to be a girls-only school, but my subject was still seen as a bit special, geeky and niche. I thought that what the industry needed was more well-rounded individuals, girls as well as boys. We needed some events to sell the subject to girls in the lower years and that’s when we thought of organising our own hackathon.

Getting started

We decided to create an event that was about one-and-a-half hours long that would be fun but challenging and would appeal to any pupil whatever their previous knowledge. Year 9 and the Autumn term were our target, given that the students would have just started thinking about GCSE choices. The girls had a rudimentary knowledge of Python at that stage in our curriculum development.

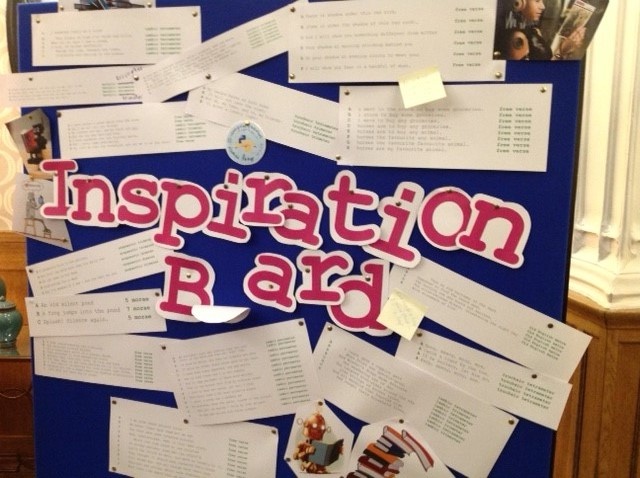

We didn’t want to get bogged down in physical computing yet. We needed something that was simple to set up. All that was needed was a laptop. WiFi would be nice for research, but not essential if we provided some reference material. We wanted to rely on the innate creativity of our pupils above all. Our Director of Innovation had introduced the idea of ‘high challenge—low threat’ to extend our already high-achieving academic girls and this seemed to fit the bill. We had also been discussing the idea of the Growth Mindset in our Teaching and Learning forum. We believed that any of our pupils could learn Python and do well at Computer Science if they were interested and inspired to do so.