The challenge of securing good progress and raising standards of attainment in core subjects has been a constant in the lives of primary school teachers over the last decade. But there is a change afoot. While progress in maths and English remain central, the wider primary curriculum is under scrutiny. Ensuring this ‘broad and balanced curriculum’ (Ofsted School Inspection Handbook) provides an exciting opportunity for schools to re-evaluate their curriculum.

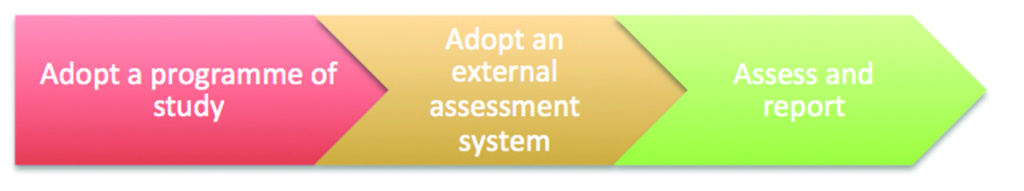

Given the emphasis on maths and English outcomes, some schools have, understandably, neglected a systematic focus on subjects beyond this core. Broadly speaking, these schools are responding in one of two ways. The first (Response A) seeks an immediate solution: purchase a scheme of work and assessment scheme then ensure the timetable indicates sufficient time is allocated. For some schools, particularly those awaiting inspection, this process is being completed in less than a term and is often led by non-specialists who are anxious about their lack of subject knowledge. Based on this rapid response and sometimes limited professional dialogue, pupils are already being assessed as ‘below’, ‘at’, or ‘above’ the expected standard in subjects like Geography and History. I would question the reliability and usefulness of this assessment.

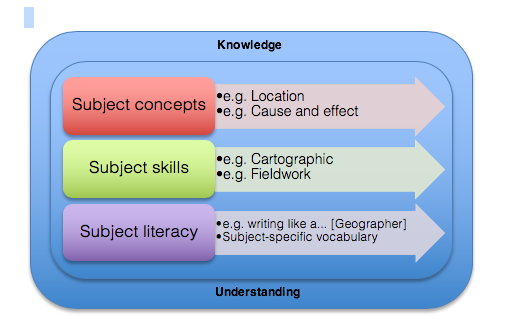

Response A creates a situation where teachers and school leaders are in danger of missing an opportunity to re-examine the curriculum, deciding what is important and relevant to the children in their context. Current DFE funding is calling for schools to share examples of their ‘knowledge-rich, teacher-led, whole-class teaching’ programmes of study to save teachers from having to reinvent the wheel. While this could endorse Response A, it could have the potential to become a tool to help non-specialist teachers understand the subject epistemology and skills needed to improve pupil learning. Response A promotes the adoption of ‘off the shelf’ programmes of study and assessment schemes. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this, indeed it can reduce workload and serve as a starting point for teachers who lack confidence in the subject, it also emphasises content delivery and can lead to superficial understanding. While children may know more ‘stuff’, they are unlikely to think and work like geographers or historians. This is because these teachers, understandably, lack an understanding of the subject’s core concepts by which they can help pupils gain deeper knowledge and understanding. Children in Geography or ‘Topic’, for example, often study a different country each year they are in school. While children may enjoy the activities and know more than they did before, rarely do I see planning which promotes a growing understanding of location and place, a key geographical concept or a significant improvement in cartographic skills (a key geographical skill) over time. Location (e.g. a study of settlement including site and situation or the influence of longitude and latitude) is developed through the study of a particular place. Making comparisons between different locations, e.g. comparing one city or country to another, then develops our understanding of place.

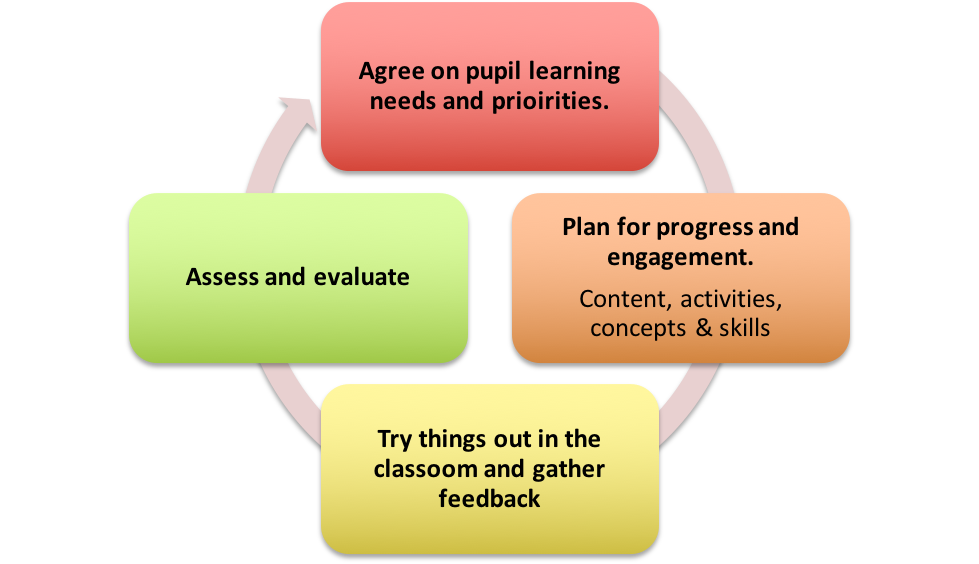

In contrast, schools adopting the alternative, Response B, have taken the opportunity to review their non-core curriculum. They are weighing up what already works and what needs to be tweaked or changed. Staff agree together on professional and pupil learning priorities and how these should be taught. They develop a curriculum framework in which they can try out new teaching approaches and material and evaluate established strategies and activities. Only then do these schools build an assessment system that helps them understand pupil progress in these subjects. This assessment information informs planning for the next topic. These schools have confidence to work on this over a year to eighteen months rather than adopt a quick fix.

So how can non-specialist teachers plan for progress? What sort of tasks and experiences help children develop a deeper knowledge and understanding of the subject over time? Drawing on GCSE syllabus requirements and the work started more than twenty years ago by Professor David Leat and aided by the Thinking Through Geography group, Julie McGrane and colleague Anne de A’Echevarria are currently working on this with groups of teachers around the North East through the ‘Leading Learning’ initiative. This work aims to support primary subject leaders to plan for progress in Geography and History while developing a planning resource for teachers that will be published later in the year. An evaluation tool designed to help subject leaders evaluate the quality of subject teaching will also be available via Vuwbo (vuwbo.com). These resources help teachers focus on three strands of progress.

Take the subject concept of location and place. If pupils only study one country after another without teachers planning longitudinally, then knowledge of place only tends to progress in line with pupils’ literacy skills, experiences or maturation. If we want to develop an understanding of the importance of location and place, then we need plan for this over time. It requires teachers to work together both to plan for learning and development but also to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching.