To flick through the pages of this magazine or visit the numerous ‘best schools of the future’ websites, one thing is clear, we aren’t seeing photographs of classroom boxes along corridors, with desks in rows and diligent children facing their teacher who is positioned at the front, as exemplars of forward-thinking education. Instead, the images of learning environments today are more likely to resemble a modern workplace, a home or a social hub, which may be indoors, outdoors, or a combination of both.

Accompanying this shift, are the changes required in thinking and practice of educators. When I first started teaching, I was thrust in front of a group of enthusiastic six-year olds, there were some wonderful colleagues in nearby classrooms, but on the whole, I was trying to work it out on my own. I’m sure those children were asked by relatives and friends, “Who is your teacher? Is she nice?” I was a very significant individual in their young lives. I was the singular point of reference, the keeper of all knowledge and the manager of day-to-day business for 25 children for an entire school year. It was a big responsibility for a young teacher in her twenties.

The thinking that goes along with the solo-teacher cannot be automatically transferred into the shift toward the shared, multi-class environments we see today. In the last edition of Learning Spaces (4.1) we saw the disruptive designs of the Rosan Bosch Studio, designing ‘imaginable, enjoyable and unique spaces’. In the interview Rosan explained, “we design spatial sequences, put on layers and end up with a school truly respecting learners’ diversity and individuality… [the process] never ends up with a square room like a classroom”. So how does a profession that has been a predominantly solo experience in a square room, shift to such an innovative learning environment?

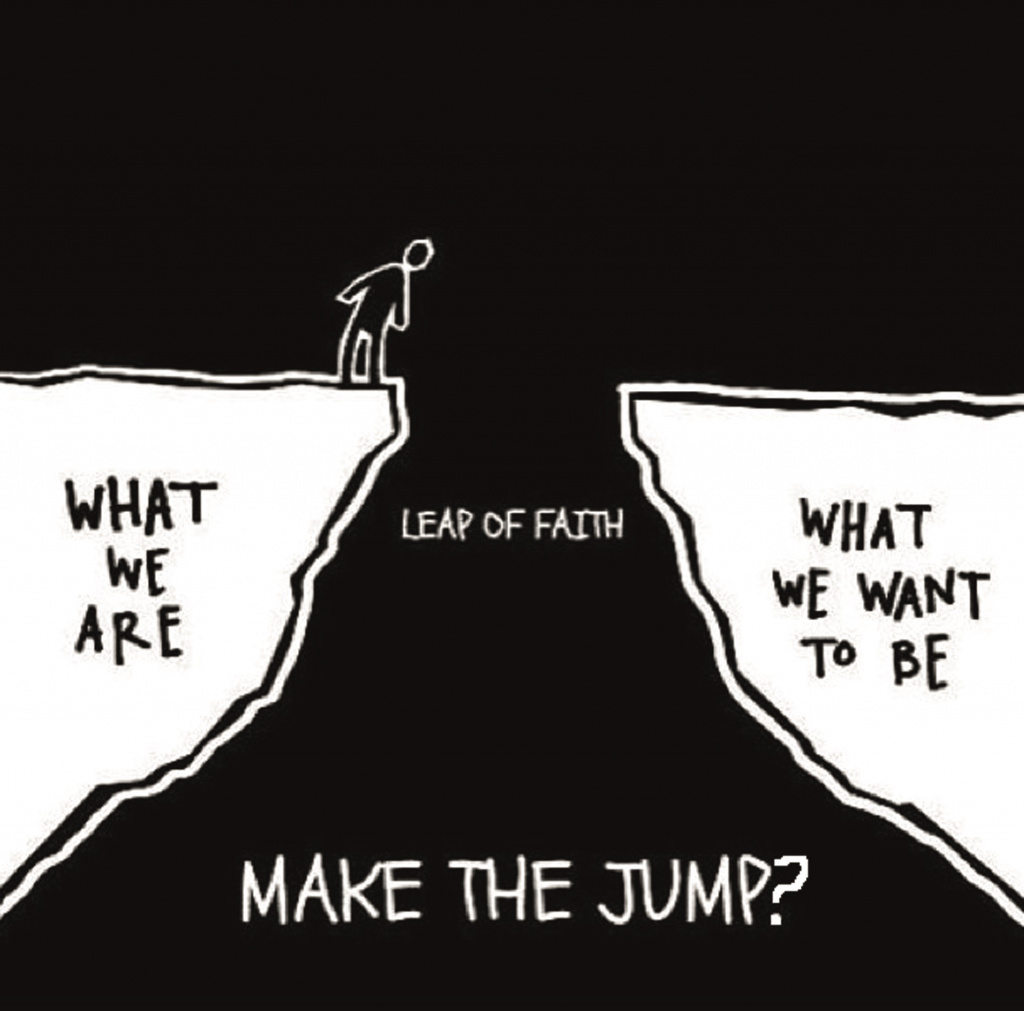

The short answer is work as a team, the long answer is much more complex because humans are complex, and change is complex. A study by Saltmarsh et. al. (2015) about teaching practices in shared learning environments concluded that “spatially responsive pedagogies tend to occur where there is less emphasis on structuring timetables, routines, sound, movement, and other variables, and place more emphasis on teachers and students learning together about how best to make use of space as a learning resource”. We need to start with the people-factor.

The buzz word, of course, is collaboration. It is a necessary attribute today. It is the basis for people working together in a productive and respectful way. However, just because we are in a room, around a table with work to do, doesn’t necessarily mean we are collaborating, as an article in Harvard Business Review said, “They were still unable to truly achieve the desired outcome because they confused pleasant, cooperative behaviour with collaboration” (Askenas, HBR April 2015). Effective collaboration is the essence of professional practice in shared and open learning environments.

The title of a book I read recently addresses the elephant in the room, “Collaborating with the enemy: How to work with people you don’t agree with or like or trust” by Adam Kahane. He makes an honest appraisal of collaboration, where “Conventional collaboration looks like a planning meeting… [but] When we are working in complex situations, with diverse others, collaboration cannot and need not be controlled”. I think this gets to the very nature of teachers working in teams in shared learning environments. If each new teacher to the team comes to the collaborative table trying to shoe-horn existing practices into the new scenario, then ‘pleasant, cooperative behaviour’ may (or may not) ensue and perhaps each will retreat to their own corner, literally, in the space and former practices will prevail.