If you read the introductory article to this series in the last Managing Schools Today, you might have taken up the suggestion of asking colleagues to analyse a time when learning was really good in a classroom they know. If so, you have been doing what this article is all about.

During that activity, you might have heard your colleagues talk about times when classroom learning was ‘hands on’ – when there was a particular product to create, or something to be enacted, or when learners made plans about how to proceed, and so on.

It’s these sorts of features that we might group together under the heading of ‘Active learning’. Perhaps some of your colleagues even use that adjective. I have been surprised how many pupils in schools use it when asked how they want their learning to be. In one survey of pupils in six primary schools, Year 6 pupils said that learning would be improved by 'more active work in groups'. Meanwhile, Year 1 pupils were using terms such as 'games in numeracy', 'more play (like we had in Reception)', 'more drama' (or 'acting') and 'more model making'.

And it’s not only pupils who say this: other research has shown that there are significant commonalities in teachers’ and pupils’ perceptions of effective classroom learning and that they prioritise active approaches.

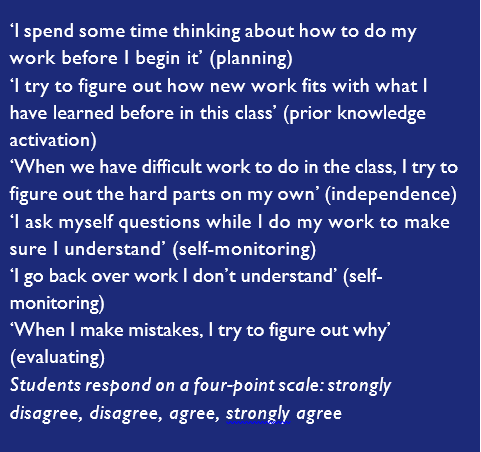

So how come we see so little active learning in the dominant model of the classroom? A study in Northern Ireland primary schools showed a trend of learners reporting less use of active learning strategies as the years of schooling increased (see Figure 1). Furthermore, those learners who are described as being of ‘low ability’ (which is a misnomer for ‘low-attaining’), report a faster decrease in their use of active learning strategies over those years. This finding can be read as a direct connection between active and attaining.